Lennard-Jones Potentials

‘She’s the odd one out,’ Kanaka heard her mother say. And even though Ma’s tone was low in the quiet of the early morning, Kanaka could tell that she had gone from being loving to annoyed. ‘They are so different – Renuka’s organised. Even when she’s cheeky, the girl’s easy to work with, has my sense of structure.’ She paused, then responded with the little laugh she reserved for Pa, ‘Oh, alright, Ramu, and pretty.’ Then, her complain-to-Pa voice rose a notch and she was saying, ‘But Kanaka, every morning, every homework session, each meal, it’s as if she’s in a dream. Sometimes I wonder what part of me is in her.’

Was it only an hour later that the water ran out? Foam stung Kanaka’s eyes as, feet sliding, she reached for the reserve bucket in the far corner of the bathroom. ‘Why can’t we keep it closer to the bath area,’ Renuka had wailed more than once. ‘Because, I know you girls; if you can reach it easily, then you’ll just use it up and not refill it,’ their mother had replied. Well apparently Renuka had done just that. The bucket was empty.

‘Ma,’ Kanaka bellowed, opening the door a crack. The thin cotton towel did little to protect her modesty but she tucked it more firmly around herself and opened the door a little wider. ‘Ma, Renuka, need water, can you bring me some.’ There was no response and Kanaka remembered that they had left already; Renuka had morning training and Ma had decided to head straight to the lab after dropping her off. ‘That way, I can be back in time for the cricket,’ she’d said with a wicked shake of her head. Ma hated cricket and the fact that everyone they knew avidly followed the game. But just as Kanaka had felt happy for being included in the grown-up moment of irony, Ma’d chided, ‘Please make sure, this once, that you’re not late for the bus.’ Kanaka’d slammed the bathroom door, ready to splash water all over the fresh towels. But very quickly the stories had begun in her head, and as she cleansed herself and ran the water down the crevices of her body, feeling light and relieved, she chatted with a man on a cloud telling him how her ladder twisted into a helix when she tried to reach him. It was a nice conversation, he listened to her and nodded when she told him how some rungs were three-slatted and stronger than others. The tension of the morning was gone. She tried for a moment to revive it when she opened the door, just to feel the power and satisfaction of being rude, but the resentment wasn’t there.

And there was no one around to direct it at.

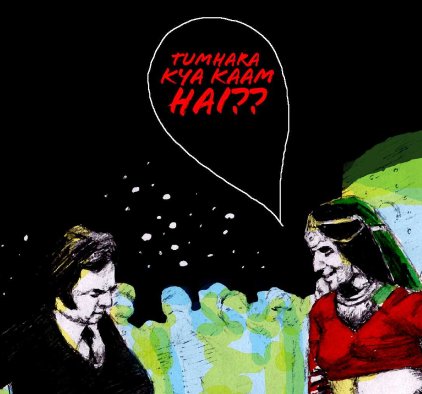

Was she really alone in the house? She wiped her eyes with the corner of her damp towel and stepped out into the corridor. Every footstep was another adventure, it was impossible to predict which way the drops leaving her toes would land. Her heels, however, made distinct pear-shaped marks on the floor, as if they were shallow energy-wells rooting her temporarily to the ground. Ma had shown her pictures, contour maps of energy-wells. Lennard-Jones potentials she had called them, that’s how lizards attach to surfaces, through weak bonds, minute attractions between molecules. I am weakly-bonded to the earth, Kanaka thought. She squatted down and looked at the droplets that had left her toes. The one from her big toe had also splashed in a series of smaller pear-shapes. Are they from the ghosts of my dead sisters who, Ma said had died inside her before Renuka and I were born? Kanaka imagined that they must have lain next to Renuka and herself eleven years ago, feeble and small, in liquid from their mother’s stomach. Ma said that if they had all been allowed to survive they would have been seven sisters in all. Maybe one of them would have been like me, Kanaka thought. What would they have been named; would they all have had names that ended in ‘ka’, like Janaka, for example – but that’s a man’s name – Sita’s foster father. We have a foster father too, Kanaka recognised. She and Renuka didn’t know who it was, only that he had given his DNA to Ma to make the two of them, and that it wasn’t Pa. Ma had told them that. Sometimes Kanaka would imitate Pa because he was so lovely and she wanted to be just like him and not like some unknown man that she’d never seen. She felt as if she were one of the threads of the twisty molecule that Ma had shown them a model of saying, ‘It makes us what we are’; whenever Pa came home from the field she thought of ways to wind herself a little more around the Pa strand.

Maybe Menaka would be a good name for one of her dead sisters, after one of the apsaras, she would have to be the prettiest of the seven. Renuka was the prettiest of the two of them and would hate it if one of their dead sisters were prettier than she was. What a fuss she’d made when Kanaka wore Ma’s coral necklace at Diwali. There was no point arguing – but you used it last time – nor did it make a difference when Ma reasoned – we agreed that you’d let Kanaka wear it at the next occasion. Soon after that Ma had split the necklace into two smaller ones. They didn’t fight about it anymore, but Kanaka always felt sad when she wore it now. And she could tell that Ma did too, it had been her mother’s.

The marks on the floor were fading, the water evaporating into the air; that’s what must have happened to her sisters, they must have pushed higher and higher up the wall of the energy well and drifted further and further outwards till they could neither hold on to Ma nor to each other, and simply just disappeared.

Kanaka went into the kitchen. The phone was ringing but she didn’t answer it. She warmed up the water in the kettle and poured it into a shallow dish. Her hair was starting to feel cold and a little sticky. She bent over the sink. Luckily Ma had put the drain cover on so she didn’t have to look down the hole and imagine all the things growing inside. Lifting the cover slightly to allow the water to run through, she used a steel tumbler to pour small quantities of the clear liquid onto her head. She could feel it trickling warmly down her neck and front and dampening the towel even more. Her chest began to feel cool, so she undid the fabric and swept it around her head to catch all the trickles. Ma’s seersucker bathrobe hung on the back of her chair, crumpled and powdery-smelling. She wrapped herself in it, and as she did, she remembered what Ma had said about lizards when she had asked, ‘But how do they walk if they are stuck to the wall? How do they lift their feet? Don’t they need to be heated or dissolved to let go?’ Gummy bears in a glass of water got sort of swollen and gooey. Maybe that’s what lizards did, even though they weren’t in water, maybe they unstuck themselves by getting kind of wobbly. But gummy bears always got a lot harder, less flexible when they dried out and lizards didn’t seem to; or maybe they did inside and that’s how they got older, like Ma, who always said she was less flexible than her girls.

Ma had said, ‘Heated or dissolved! You are asking me how they get the energy needed to get out of the well,’ and hugged her. Kanaka didn’t know why except that it felt nice. Then she’d said, ‘That’s a great question Kanaka,’ which usually meant she wasn’t going to answer, like when Kanaka’d asked how they got the other man’s DNA inside Ma’s tummy and Renuka’d snickered and whispered, ‘You can’t ask Ma things like that, god, you’re such a nerd, don’t you know anything,’ and Ma had told her it was a good question and asked her to drink her milk and hurry up with her homework. But about the lizards Ma said, ‘I believe you have something of my mind after all. You’re right, they do need a boost, and the lizard brains send a signal to the soles of their feet to say lift up, just as we do. Except in their case, the molecules on their soles turn around a little and the attraction to the surface they are attached to is reduced, and they can lift one part up. At the same time they put another part down and attach, so they don’t fall off the wall. Attract, release, attract, release.’ She’d laughed and added, ‘Sometimes those soft bonds are the wisest.’

Kanaka wasn’t really sure what Ma meant by that. But she thought about her family, her father, and Pa and Ma, Renuka, and her lost sisters and she thought she understood. Sometimes, you had to be able to climb out of the energy-well so that you didn’t crowd it. Lizards lifted one part of their foot up to make room for another. People probably had to let go of one person before they could connect with another. Maybe that’s why her father had disappeared, and her sisters, so as to make room. Was it Ma who had given her sisters the boost to go? Had she lifted them so far out that they couldn’t find their way back? But how had she chosen which of them would go and which ones would stay? Maybe she hadn’t, maybe Renuka and she had simply held on tighter?

Renuka would hold tighter than Kanaka if Ma ever chose between them; Renuka was the one who always won at tug-of-war. Maybe, Kanaka thought, she should make the choice herself rather than wait for the tug-of-war. She could choose to go now, when the house was empty, rise up, and like the water vapour, float away. If she held her breath, her body would fill with air and she would be buoyant, like a balloon, and catch the currents. Would she drift to where her sisters were? Before pinching her nostrils shut she burrowed into the dressing gown, covering herself entirely to fill herself with Ma’s powdery smell.

When she opened her eyes, Kanaka found herself bundled in the dressing-gown and on the kitchen floor, but her head lay cradled in her mother’s lap. She was still softly bonded after all.