Boys and Girls Together

On a rooftop, under a full moon, were three young women. One was sturdy, dark and angry, one thin and trembling. The third was bare above a low-slung shalwar. She swayed in time with music that came from a radio playing Big 92.7 FM on the roof of a next-door house, one storey higher and the width of a narrow driveway away.

The young man standing on that higher roof turned up the volume, and thought of men in films who leap from roof to roof to wall to ground, weightless.

This night-time recreation was far from typical of life in the middle-class, middle-sized, sleepy city, yet it became almost inevitable on the day a refuge for women opened on a quiet backstreet, at the same time as a sign appeared in front of the neighbouring house, describing it as ‘Anand Lodge’.

The lodge, an aging bungalow like all its neighbours, had recently grown another floor, which the owner divided into rooms that could be rented by the legions of students from the hinterland who couldn’t find a place in the local university’s crowded hostels. If the owner had seen a lot of bossy women with short hair coming and going next door, he’d not given it a thought as he dreamt of the rents that were soon to be his.

And the group of women activists next door, setting up the refuge in an old house donated to them, had been far too busy filing paperwork and writing project proposals to pay attention to the lodge. Besides, they were blinded by their own courage: never had such a shelter been available to battered wives or abandoned girls in the region. They were pioneers!

When they finally realised what the lodge was, they stepped across to express concern. They suggested converting it into a hostel for female students.

Their neighbour said, ‘Too much responsibility, taking care of respectable women.’

His attitude toward their charges was clear from the way he said ‘respectable’. They asked him to at least block the windows in the wall that abutted their driveway and front lawn, but he said he could see no reason why he should spoil the natural ventilation in his finest rooms. He suggested they keep their women inside if the exposure bothered them.

How was that to be done? The power was off three hours out of every day all over the city. Unlike the lodge, where a generator shook the walls of the refuge’s kitchen with its roar and belched smoke into the women’s midday meal, the refuge had no alternate arrangement for power. When lights and fans went off on sultry days, the women went out into the open space in front to rest or work in the shade of the two big mango trees. The men, from their windows, watched.

Pressure in the city’s old pipes was not the best. Water trickled out of taps from about six in the morning until eight-ish, and again for an hour or so in the evening. To supply his cash-cow of a top floor, the Lodge-lord installed two huge tanks on the roof and inserted a pump in the main supply line that could suck up water to fill them.

No such luxury for the women. They had to go out to the small reservoir that the previous owners had excavated to collect water for the garden. They had to fill water from the outside tap. They rolled up the bottoms of their pajamas so that sloshing buckets would wet only their bare feet.

Young men sat staring out over open books. Water splashed and cloth clung to calves, ankles glistened. The men watched even the dusty-haired woman whose face was as blunt as her brain, because she sometimes forgot to close the snaps at her kurta’s neckline, or she hiked up her top to catch her sagging pajamas, which once had shown a glimpse of buttocks – not very round, but buttocks still.

Even abandoned wives with buck teeth had breasts.

Minoo was as thin as a supermodel, though recovered now from the TB that had taken her family and sent her to the refuge. When it was her turn to wash the bed sheets, she couldn’t lug them around, and sat on the stone bench beside the reservoir, soaping and pounding the heavy cloth. As she gathered the sopping armful to her chest for the fourth or fifth time, she saw the sunlight glinting off a pair of glasses in the window facing her. Laughter dropped from above, followed by, ‘You’re a very sexy, sexy thing,’ sung in a nasal tenor.

Minoo dropped the sheets and ran toward the house. Wet cotton tangled around her feet, and she fell. Her knee puffed up to the size of a small watermelon. The chairman of the refuge’s Managing Committee lost an entire day of work, sitting around the government hospital with Minoo, waiting for the doctor, waiting for the

X-ray, waiting for the doctor again.

The group decided something must be done to increase the women’s feeling of security. They put an ad in the newspaper inviting applications for the post of house mother.

But then notes started flying from one of the windows, delta-winged stealth bombers carpeting the driveway with bad poetry and crude drawings. An orphaned teenager named Nisha, whom the men had started calling ‘Kaali’, because she was both dark and fierce, began to throw the notes back, wrapped around rocks.

Emboldened, other women took up the game, although they’d only throw and run back under cover, laughing.

Their aim was awful. Almost all the missiles thudded harmlessly against the bricks. Only one, by chance, hit a pane, and the owner of the lodge rushed to find out what had broken.

This time, it was he who initiated the talk with those in charge of the refuge, but he didn’t walk out his gate and into theirs; he summoned them.

‘What is this?’ he said, with a steely pause to allow them to examine more closely the amateurish and rumpled drawing of obviously male and female figures.

The women blushed.

‘Such obscene things are being thrown everyday into our windows. And bricks and stones – it’s a miracle that no one has been seriously injured.’

The women ended up paying for damages. They said it was the boys who had scrawled such things on pages torn out of their notebooks, but he said boys from good homes would never do such a thing – though he did not, of course, believe it. Personally, he blamed the lapse on modern movies and suggestive TV songs, but he wasn’t about to admit that to those women.

The Managing Committee began to realise how difficult the task they’d set themselves would be. They’d pictured meek victims of domestic violence coming to the refuge, brides thrown out by in-laws lusting for larger dowries. But instead of such docile, grateful women, they had needy girls like Minoo, uncouth rebels like Nisha, and what their neighbour called daily ‘cat fights’.

Only one response had come to their advertisement. A woman who’d retired as matron of a dormitory at a girl’s school was interested in the house mother’s job, if she could have at least another thousand in salary, a cell phone and a proper room. Again, they made their rounds with begging bowls.

Mrs Jacob was hired, and, like magic, a happy month followed. The weather cooled and, it being the festival season, many of the boys went back to their villages to celebrate with family. The Michelangelo of doodled Eros never returned – the Lodge-lord told him not to bother.

The young man who took his room was called ‘Pandit’ by the others – because of his caste more than any great degree of learning. He’d earned an M A in Political Science somewhere and was attending coaching classes in town, preparing to make his third attempt at the civil service exams. A cousin who’d got through on his sixth try was his inspiration.

Pandit had a loud motorcycle – how could the women not notice? He also had wheat-coloured skin and deep dimples. Nisha had never seen anyone so like a movie star. She soon figured out his daily routine, and began to saunter down the drive, hips swinging slightly, at around the time he went out. Sporadic whistles followed, and a suggestive rendering of ‘He whose wife is black….’ But she ignored them.

And one day she timed it perfectly. Pandit was in front of the gate, in nicely fitting jeans, swinging a leg over the saddle. Nisha’s hands, moved by a higher power, slid the bolt back, and there she stood within a few feet of him as he jumped on his starter thrice before the old bike came alive and carried him away.

The guard came out of his hut and asked her what she thought she was doing, stepping outside alone. Nisha told him he was an old man who should mind his own business.

He did; he reported the rude rule-breaking to Mrs Jacob, who called a meeting to remind the inmates that they needed to be careful of the reputation of the refuge. Going outside the gate was only permitted for groups, with prior permission. She did not look at the forty-year-old abandoned wife as she said this, but at Nisha and others of the younger contingent that seemed to be overrunning the place. ‘Idle minds are the Devil’s workshop,’ she reminded the Managing Committee, which then struggled to arrange funds through a government scheme for self-employment of women. Sewing machines and a tailoring teacher appeared, and some of the women, including Minoo, found new purpose in life – earning two rupees per piece for sewing together plush animals on contract.

Nisha cursed when bits of fuzzy cloth ran off in unintended directions as the machine went wild. Mrs Jacob scolded and sent her back to fetching water and cooking chapattis over a wood fire in the open air. Nisha picked a spot for cooking that had an uninterrupted view of the third window in the lodge’s top floor, Pandit’s.

One of the new girls said she simply couldn’t sew, but with such a gentle smile that Mrs Jacob didn’t mind. The poor child was still adjusting. There was something appealing about this new one, Rekha. She was slim and soft-spoken, tidy. She had delicate features and was surprisingly pale. Mrs Jacob, who wore long sleeves and a scarf when she went out in the sun to maintain her own degree of distinction from the darker masses, imagined that Rekha must come from a good family, fallen on bad times.

Besides, she’d been told that arrangements were being made for Rekha to study. Money appeared for her, and a satchel full of books. Rekha was told to go to the retired school teacher who served on the Managing Committee for Class XII tuition.

Nisha exploded at the next meeting. Why was Rekha shown such favour? How could she go out alone when it was against the rules? Why couldn’t she, Nisha, study, instead of slaving away? She’d finished the Class X Board Exams, so had Minoo – why wasn’t someone taking care of them?

A hurried Committee meeting was called. Members passed the hat yet again, and hired tutors for Hindi and Geography. The three girls would go, together, to the retired teacher’s house for English and History, and Mrs Jacob would ensure that they spent time memorising guidebooks. The Committee hoped they had bought peace, at last.

In new outfits stitched by the tailoring students, the three walked out the gates, squeezed into a rickshaw and went across town to read ‘Julius Caesar’ and ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’ and recite once again who ruled after whom in Agra or Delhi, and which freedom fighters did what.

This unexpected parade of girls almost silenced the inmates of the lodge. ‘Good Morning, girls’, in English-medium school kids’ sing-song tone, and a whistle or two greeted them on the way out, but Nisha shouted back, while Rekha walked through with queenly indifference, linking arms with Minoo to get the shy girl through the gauntlet. They gossiped all the way to tuition, played with the teacher’s pet dog and generally reacted well to a little freedom.

One day the teacher gave them a practice test (Rekha did the best, though that wasn’t saying much), and it was more than an hour past their usual time when they reached home. A motorcycle roared up as they were counting coins into the hand of the rickshaw man. As the engine still purred, Nisha rushed to the gate of the lodge and swung it wide. Pandit gave her a smile and a mock salute, and she stood there, one large paralysed grin, until Minoo tugged her sleeve.

After this, Nisha became a fount of questions during coaching sessions. The teacher was encouraged by the sudden interest and gladly gave the time needed to guide her. But despite Nisha’s best efforts, only once or twice a week would the arrival of their rickshaw coincide with a glimpse of Pandit. On such serendipitous days, Nisha hopped to the job of opening the gate. Pandit started calling her ‘Respected Gate Keeper’, which melted Nisha into a continuous happy sigh, until she noticed something like the expression of a man who had died, but not yet fallen down, whenever Pandit’s eyes landed on Rekha.

‘Rekha never breaks wood for the cooking fire or kneads the flour,’ Nisha announced at the next monthly meeting, inflaming her own anger with mental pictures of the way Rekha spent her days sweeping with languorous strokes, tidying her cupboard, or lying on the takht in the sitting room with an open book for an excuse.

‘I thought you liked to work outside,’ Rekha said, softly. She went and whispered with Mrs Jacob for half an hour after the meeting, their heads close in the office, shooting covert glances at Nisha.

Nisha went out to release pent-up energy hauling water, and in the dusk she saw him there – Pandit, a pale shadow in the window, looking straight out over the driveway and through the trees to the front door where Rekha stood silhouetted against the light inside, stretching her long, delicate arms. The difference between his face at that moment and the lazy smile he gave his Respected Gate Keeper was too much to bear.

Studies did not go well from this point. Nisha challenged every word that came out of Rekha’s mouth. ‘How can Brutus be the hero of the play?’ she questioned, ‘He gives a boring speech and makes so many stupid mistakes that a war gets started….’ And so on, whatever the subject.

But, of course, Nisha could say none of this in correct English, leave alone write it with proper spellings, any more than Minoo could write anything beyond what she read in the ‘Vidya Guide’, with random words forgotten.

The teacher gave an impassioned lecture on how they must work harder to lift themselves out of the morass of dependency where fate had hurled them. She said they could be anything, but then had a flash of memory: the girls in the school where she had taught, smart, connected – even their Hindi was only half English. She told the Committee she no longer had the time to tutor, or even to serve as a member, as her own education consultancy was growing.

Minoo cried that she’d never be able to play with the teacher’s dog again, but then she really did try to study. She sat under the trees, reading lessons in a puzzled mumble, when a young man with a nice, open face called out, very politely, to ask if she could return a pen that had fallen out his window. She went over, and had just picked it up to toss it back, when Nisha bustled up and snatched it away.

Minoo ran off and cried some more. But it was really cold inside. She soon went out into the winter sun again, and within a few days it became second nature to listen for small signals from the middle window, from someone who wanted to talk softly about nothing much. She kept an eye out for Nisha, but only to avoid her. She spent more time with Rekha, who didn’t laugh when she said she thought her quiet boy was wonderfully sweet and smart. Rekha said he looked nice.

Nisha couldn’t understand why everyone seemed to turn against her. Such loneliness engulfed her that she could no longer feel pain when scolded. She forgot her studies and concentrated again on being in the right place at the right time.

‘Looking for Pandit?’ a boy she’d nicknamed Rat called out at her one day, ‘Hurry, hurry. He’s just on the stairs.’

‘Asshole,’ she replied and threw the nearest object – just the smallest corner of a brick – at him.

Mrs Jacob saw it from the doorway and was compelled to dish out exemplary punishment: two weeks without setting foot outside the house.

And that was how Nisha found the stairway in the back of the storeroom that led to a door at the top that could be opened without a sound, once she put oil on the bolt. From there she could glide to the corner of the roof nearest the lodge, and look out toward the window in which a shadow could sometimes be seen.

Soon the inside of the old bungalow began to warm up. Mrs Jacob had a small cooler in her room; its fan blocked all other sounds. But in the old drawing room, where six beds lined one wall, four another, women tossed and turned. An anxious Minoo heard sounds in the dark. She shook the next girl awake. They took each other’s hands, went out to find a line of moonlight silvering the stairs.

How miraculously cool the breeze was as they stepped through the door, it almost chilled as it touched their sweat-damp clothes. The girls saw Nisha, standing by the edge of the roof. Above, on the nearest corner of the taller lodge, was a solitary figure sitting on the parapet, smoking and sipping from a small bottle. The girls watched, without moving.

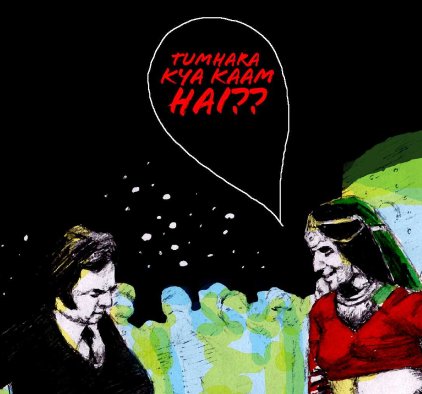

Tossing the glowing end of his cigarette away, he stood, and from the height and shape it was obviously Pandit. He gave a bow, and Nisha waved. He saluted.

‘So you come up here to drink liquor,’ Nisha called up to him, in as cooing a voice as anyone had ever heard from her.

‘Nothing wrong with a little intoxication, is there?’ he asked, and she went weak with a rush of feeling that nasha, sounded so like ‘Nisha’, as if her name had been in his mouth.

He’d pulled the earphones out of the small radio he had beside him, and faint music came out.

‘We could dance,’ he suggested.

Minoo, hanging back in the shadows, could feel the beat as he turned up the volume, she thought of dancing and of Ras Lila – once, on the way to tuition, she’d seen a painting of the scene on black velvet at a roadside stall.

‘You first,’ Nisha called up to him, giggling.

Then Rekha came out of the shadows, walked by Minoo, stepped in front of Nisha. They watched as Pandit leaned toward her, as though drawn across and down to their roof, as though he might take that leap.

She swayed – it could only be called that, not dancing. Her fair face shone, silvered, and night shadows picked out her straight nose, the arch of thin brows, the rapt, inward look.

He turned the music up and began to sweep his hands, slowly, moves he’d seen in films and never tried before.

Rekha took the silver-threaded dupatta off her shoulders and waved it over her head in shining ripples.

‘What are you doing?’ Nisha barked, but no one listened.

Rekha let the dupatta fall, it spiralled through the air to the ground far below. As Pandit went still and the moon caught his shining eyes, she pulled off the worn kurta in which she slept, and there she was, a silver body, perfectly shaped, undulating with the music. She didn’t lift her eyes; she didn’t stop.

Minoo blushed as she thought, as she did sometimes, of being bare like that, of the quiet young man watching her like that.

Nisha charged downstairs. The others barely noticed, until heavier footsteps pounded out onto the roof and a slap echoed from the wall in front, from the top of which man and music had abruptly disappeared.

Mrs Jacob called Rekha a whore who deserved to be turned out into the street. A faint light was dawning before the refuge settled back into silence. Nobody got up until almost eight – shocking, in itself, such slothfulness. More shocking, Rekha was gone, along with her two best sets of clothes and the three hundred rupees one of the girls had slowly collected from tailoring work and hidden from everyone, she thought, behind a picture of a baby Sri Krishna.

The Committee came running. The women’s police station was alerted. A penitent Mrs Jacob began to cry that perhaps she had been too harsh, the girl must have psychological problems. It was then that the Chairman let her in on Rekha’s secret.

They’d needed money, she said, to hire Mrs Jacob, and everyone knew the only money pouring in these days came from AIDS-related work. And so they’d taken in some girls, of which Rekha was one, whose mothers were HIV positive sex workers – just the mothers, mind you, not the girls. To prevent prejudice, they’d told no one.

Mrs Jacob tried desperately to remember if she’d ever had a scratch that might have touched a scratch on Rekha’s arm during a maternal hug, or could a spoon the girl had used ever have reached her without thorough washing. However loudly the Chairman insisted the girls had been tested, they were healthy, the house mother abruptly left.

Whispers spread. The Lodge-lord demanded the removal of the refuge from this respectable street. The Committee, broke and discouraged, admitted defeat. The inmates were dispersed – some to government protective homes where only a court order could get them out; some to other refuges, in other cities; a few to the scrappy lodgings they could afford with whatever jobs they found. Nisha became one of those, throwing pans around in someone else’s kitchen, yelling at her neighbours in a slum.

Minoo expected her quiet young man to take her away, but his parents took him off instead. She was put into an institution in the Gandhian tradition, encouraged to work hard, study and wear homespun. She ended up teaching in a nursery school, earning one thousand rupees a month, and staying with an elderly activist for whom she cooked and cleaned in return for room and board.

Pandit passed the preliminary exams for the civil service, and was even called for an interview before he was rejected that year. He’s still trying and still at the lodge. He goes to the roof sometimes and remembers that night, though in memory the breasts grow larger, the hair longer, swinging around a face that is turned up, around large eyes that are fixed on him.

As for Rekha, she vanished.