Do It By the Numbers

1

There is a difference between hitting and beating, and if you didn’t know this before, you certainly know it now. You look in the mirror as you listen to your friend. She speaks of these differences over the phone, and while once there were wires carrying your words to each other, now they pulse in thin air trying to find the way. Beating isn’t what happens among your kind, you learn. Beating isn’t what happened to you, you learn. Hitting is when it happens once; perhaps twice. There is also, you learn, a hierarchy to truth.

She explains that she called him to ask the ‘why’ and the, ‘oh, please, why?’ She describes how broken he was, and how remorseful. She tells you how his voice broke when she spoke to him, and his heart. With him she wept like a child. Repentance, she says, withdraws the weight of the sin.

By the time she makes the time to call you, by the time you find the time to tell, your truth has taken its usual seat, in the lower strata, in the outer halls, to echo to itself.

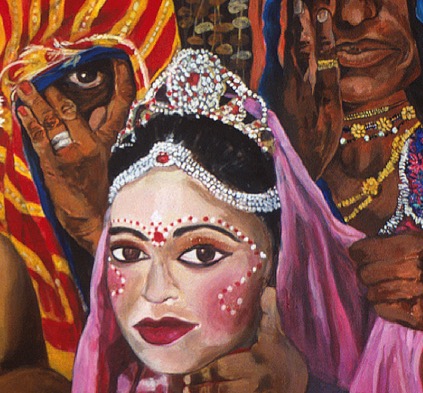

You look at yourself in the mirror as you listen. This is not vanity, this morning this is survival. As she speaks, you see the fresh scar on your left cheek, the one that digs much deeper than the surface-mud of your skin. Not much light enters this room because the deep grey walls of the building next door absorbs but returns nothing. You listen even more closely as she weeps to you while explaining how his despair is all about love. You do not try to tell her about yours: neither your love nor your despair. Her tears pour into your ears like molten rock; fluid but thick.

You think of the scar on your child that you cannot see, but which she is making you treat with brightly coloured band-aids. You think of the little icepack she asked for although she couldn’t tell you exactly where it hurt. You think of how your mother keeps disappearing into the other room; she thinks she is clever in hiding her tears, as if you cannot tell. You think of how your father doesn’t dare come near you. You think of how you are a pariah still, though now of a different sort than you were the day before. You think of how yesterday your veins had buzzed with their disbelief. You see how their eyes can see but look away. You see how today, even sight, sound, and touch change nothing.

You think of it all as you watch that scar, the one that will always remain, even when your skin finally seams shut and you let life back into your life. But now you listen to your friend explain how hitting is different than beating and you realise how easy it is for the spun-sugar wonder of trust to dissolve.

So one day it is in front of a mirror, one day at a dingy lawyer’s office, one day over the phone you learn (that you need to learn how) to stay calm and answer questions like how many times and for how long and do you think he meant to, I mean really meant to, and, but he’s never done it before.

You learn that it’s high time that you learn how to ask the questions, define for yourself the rules of the game: how many times does it take to turn a hitting into a beating? Is it hitting or beating when it’s not just you but the mother he called mother as well? Is it hitting or beating when you are up against a wall? Is it hitting or beating when it’s your child that gets sucker-punched? You need to learn how to ask all these well-meaning people whether it constitutes Physical Abuse when it is a brother doing it, whether Intimate Partner Violence still works as a term when it is friends who are on either side of the hammer, whether Gender Equality is still strong in their hearts when they need to defend what (you know) is indefensible.

2

The heat of memory burns fierce just under the skin.

You learn how laughable the urgency of your rage is. Your grief changes naught in the world.

3

The primacy of your outrage decays as you learn that it’s just not nice to hold onto anger (for so long), especially when he is suffering so. You learn that your life becomes an open book where everyone writes their names. You learn that some pages cannot be turned. You learn that the only way to keep the spine straight is to hold down the pages on either side with weights; they need not be equal.

4

So there is a difference between hitting and beating and if you didn’t know this before, you certainly know it now.

You sit in front of a screen as you listen to another friend from afar speak of these differences, and nothing, she tells you, there is no difference at all. You find that sometimes her words on the page carry more than her voice. You wonder at another friend who arrives out of nowhere to hold your mother when you have all but failed. You listen to the one who later breeds knives in her bones give you release of sorts: it wasn’t you; it was never you. And you know that the ones who know that are the ones who can spin sugar out of thin air.

And you hope you have time to relearn how to hold this spun sugar in your mouth so it does not melt into nothingness.

It’s a learning game for you mostly, where your eyes open anew, held unblinking in midnight rages. It’s a learning game where silent streets plead broken-voiced and the past speeds off in skid marks and the smell of hot rubber. You do not know it yet, but: ‘truth is subjective’ will burn your throat; a hand on your cheek will break your spine; a door slammed shut will gunshot your heart. You will learn that no matter how many years go by, what you have healed will rupture with ease at certain lines: she made it up; I don’t want to know; she’s exaggerating; does it still matter?

The heat of memory burns fiercest just under the skin.