Sridevi

One thing was clear in our minds – we were not going to start a family until we knew what we wanted to do, where we wanted to be. I didn’t have a clue about children and sure enough, I found myself taking care of one within days of moving into our house on Chidambaram Street in Bangalore. It was a house divided into a left half and a right half. For the first two months we had a bachelor as neighbour in the left half of the house but soon after that a young couple moved in. They had a toddler and were expecting another. Gowri and I became good friends and soon I was holding her hand as she went through the morning sickness phase. More often I was holding the hand of the toddler, Sunita, a super active child of three who was happy playing all the time with her little rag doll and make-believe house.

My sister had a houseful of toys even though her own had long ceased to be toddlers, and soon after Sunita moved in, I went across the city to her house and brought back a suitcase of toys and picture books for Sunita to play with whenever her mother needed to take rest. Sure enough, she started spending more time at my house than at hers, and it made sense that Gowri too should join. We spent many afternoons together. Her husband, Madhavan, was not given to much talking and he was rather serious about his readings in philosophy. So we did not get to know him much.

Three weeks before her due time, Gowri was rushed to the hospital, and her little son was born on a Monday evening. She had haemorrhaged profusely. Her mother came from Mysore. Nothing could be done and Gowri passed away three days after giving birth to little Kannan. Families from both sides came, and while all the ceremonies were going on next door, the least I could do was to take care of Sunita and the baby. After the rituals were all over, Madhavan’s parents left, taking the children with them. We took Madhavan under our wing. He was totally distraught. He refused to eat with us, but when Siv took some food to his house, he did not refuse. He spoke little but slowly accepted our help and came in to have dinner with us every day. Whenever he spoke, it was about his children. His parents insisted that the children be with them and they urged him to come back to Chikkalur, he said, and to take up a clerkship there. Siv thought it was a good idea, and told him how important it was for him to be with the children. ‘I miss them,’ he said, ‘Just for that, I might move back home.’

But next they would be on his back all the time to get remarried, he said, and he couldn’t bear that.

The following Sunday, when Siv and I were lazing around, I saw a young woman, carrying a small suitcase, opening our gate. There was a knock on our door. I went and opened it. The woman fell back with her hand on her mouth, fear in her eyes. Then she saw Siv behind me, and her face cleared. ‘I am sorry,’ she said, ‘I seem to have come to the wrong address. I thought this was Number 21.’ ‘Yes it is,’ I said. ‘21A.’

‘Oh, is there another 21?’ she asked.

‘21B,’ I said, pointing to Madhavan’s door. ‘I saw Madhavan go out a few minutes ago,’ I added. ‘I am sure it is only to the corner newspaper stand, come in and wait for him.’

She hesitated and then came in. Siv went away to the bedroom so she would feel more comfortable.’

‘My name is Maru,’ I said.

‘I am Sridevi,’ she said.

I thought she would go on to tell me how she was related to Madhavan, perhaps a sister or cousin.

‘I am sorry to be troubling you,’ she said. ‘I thought he’d be in since it is Sunday.’

‘It is such a tragedy,’ I said, ‘that anyone in this time and age should die of bleeding at childbirth.’ I spoke about how quickly Gowri and I had become friends, what a lovely person she was.

She nodded, and wiped away her tears.

‘How is he?’ she asked.

‘He is devastated,’ I said, ‘and he misses his children.’

‘I thought so,’ she said, ‘that is why I have come, to take care of them.’

‘But they are not here,’ I said.

‘I know,’ she said. ‘We must bring them back.’

‘That would make him less sad,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘we must bring them back.’

I didn’t know what else to say and we sat silently.

‘What is the baby’s name?’ she asked.

I said, ‘Kannan,’ surprised that she did not know. Who was she?

Again there was silence. Then I saw Madhavan returning, newspaper in hand.

‘He is back,’ I said, with some relief, for the silence was uncomfortable.

She rose and picked up her suitcase. He looked at her, and stretched his arms towards her and then drew back. ‘You here?’ he said, ‘Oh God, I can’t believe it, you are here!’

He unlocked his door and they quickly went in. We could hear their voices but could not hear the words.

That evening, I knew who she was. Indeed, the whole street knew who she was. For Paru, our local gossip, who lived across the street from us, cried as though Gowri had died all over again. Standing on the street, she heaped curses on ‘the harlot that has taken Gowri’s house and bed before her ashes had grown cold.’

It came out that Madhavan had had this ‘dasi’ for years, had been infatuated with her even before he married Gowri. He had gone back to his home town so often, not because he was a good son but because of this woman.

A few days later, our neighbours went away and came back two days later, with the children.

No one visited them. Madhavan barely greeted us on his way in and out of the house. But Sunita came as usual and played with the toys that had lain in their basket in the corner. As when Gowri was alive, I read to Sunita from the picture books, which were in English or Tamil; since I did not know enough Kannada to tell a story, and Sunita was fast learning Tamil from me, I read aloud in Tamil from the English picture books and conveyed the meaning through the pictures and gestures. Much as I wanted to, I did not ask her about Sridevi.

It was when I heard Paru referring to her as Moodevi that I knew I had to befriend her. It was a whole week before I took courage and knocked on their door after the men had gone to work. It was not kindness that impelled me but admiration, perhaps even envy, a sort of vicarious pleasure and pride at her courage. We, in our humdrum lives with our mediocre outlook have so little courage that we shy away from anything unusual. We don’t dare, we cower in fear for what people might say. Here was a woman who did what her heart told her to do even though her reason and experience would have told her it entailed pain.

The house was clean, tidier than it was in Gowri’s time for Gowri, poor thing, had been sickly all the time I knew her. Sunita was playing with her rag doll. I rebuked myself for not having given her some of the toys she played with when in my house. Sridevi completed the lullaby she had been singing to Kannan who slept peacefully in his cloth cradle. She had a beautiful voice, and it was clear she had classical training.

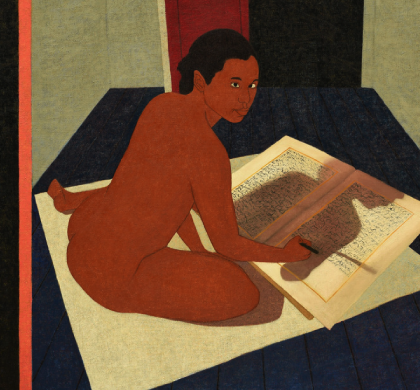

What amazed me was Sridevi’s serenity. Not her beauty, which was breathtaking, or her voice, which was more mellifluous than any I had heard, but her serenity.

Another week went by and another. I saw to it that Sridevi came out when the vendors from whom I bought vegetables and fruit stopped at my door. She never left the house, but she did work in the patch of garden at the back of our house, sowing coriander and a few flowers. Madhavan did the shopping for she refused to come with me to the corner store. In a way I was relieved when she refused for I did not want words from the other women on the street.

Then one day, a tonga stopped at our gate and a woman got out. She was dressed in silk, unlike Sridevi who dressed in plain cotton saris, but she looked like an older version of Sridevi, an aunt or mother, it seemed to me.

She stood at the door and I could hear the commotion. Voices were raised. Sunita ran into my house and huddled in the corner with her toys. ‘Amma,’ I could hear Sridevi shout, ‘I will not come back with you. Never again to the House and that life.’

By now, a few women had come to our gate to listen in to the conversation that was taking place on the verandah, for Sridevi had not invited her mother to enter.

Her mother’s voice was patient. She told Sridevi she was too impetuous, impractical. She would tire of Madhavan all too soon. ‘Of course she will, lascivious siren’ said a neighbour.

He was just a simpleton who could not afford to keep her in the lifestyle she was used to. ‘Just you wait and see, she will run through all his savings and then leave him,’ added another.

What was she doing in this hovel instead of their mansion? With a man who didn’t earn in a month what she could earn in a night?

Sridevi’s voice came loud and clear. ‘Don’t you dare stand in his house and insult him. Leave us alone, this is my home and I refuse to come back with you.’ ‘Her home, indeed, the whore,’ said the first woman.

After several more heated exchanges, the mother flounced out, shouting, ‘You have ruined my reputation. When you tire of your pauper, don’t you come begging back to us. When you lose your youth littering for your lover, don’t expect you can return to us.’ She haughtily got into the tonga and left.

Sridevi went into the house and shut the door. The neighbours went back to their houses, licking their lips in anticipation of the treat they could share with the rest of the locality. I came into my house and hugged lucky Sunita to my heart.

This is a story from a work in progress provisionally titled Maru’s Memoirs, where many of the stories are set in the 1960s.