A Sweet Life

Lalitha had seen enough of life to know that anything could happen to girls who went missing. Anything, the worst possible thing.

She swung open the dried goods cabinet and said, ‘Maybe she’s been kidnapped.’

‘Amma,’ Andalamma said, as if she knew everything. ‘Who will kidnap Padma? The girl is black as coal and has no brains.’

‘This is Kali Yugam. People are smuggling innocent girls to Delhi and Bombay and selling them off.’ Lalitha measured yellow lentils. ‘You searched the whole market?’

‘Every corner, Amma.’ The water plopped as Andalamma washed long drumsticks in a broad vessel.

‘Did you search on the road to the market? The theatre? The clinic?

‘Everywhere, Amma. No one has seen Padma.’ Andalamma’s knife wobbled as she cut the drumsticks. These days, it was Padma who did the cutting and fetching.

‘How long does it take to buy two packets of milk?’ Lalitha said. ‘Maximum half an hour. Even for our half-witted Padma.’

‘It’s as if Bhoodevi opened up and swallowed her, Amma.’

How, in the name of Lord Ramakrishna, to explain this to the girl’s parents?

‘It wouldn’t have happened if the milkman’s son had come today.’ Lalitha thumped the lota of lentils down on counter for the cook. ‘It’s his fault I sent Padma to the market alone. Useless rascal!’

*

The previous morning, the milkman’s son had rinsed the wide-rimmed pan and presented it to Lalitha with his usual, irritating flourish.

She peered in, searching for the hidden compartment or secret tubing that released water into the milk so this boy, like his father before him, could skim his little profit off at her expense.

Lalitha leaned back on the stone ledge. ‘What is the use of this show? The buffalo can give the milk it wants, but you will give the milk you want.’

‘Amma, every day it is the same milk.’

‘Every day, the milk gets more watery. The curd gets thinner. The ghee is vanishing.’

‘If I can make water appear and ghee disappear, Amma, I must be a magician.’

‘What did you say?’ Lalitha sprung off the ledge. Was he trying to mock her? Was he?

The boy’s bony hands stiffened around the udders, and the buffalo mooed and shuffled.

‘Just because you are tenth class fail, do you think you are a Collector, or a Zamindar? You’re just a petty thief, pinching and nibbling from the edges.’ Lalitha crossed her arms. She glared at the boy, who shifted jerkily on the wooden stool, nearly dropping the milk.

That was yesterday. Today, the milkman’s son had absconded from his duties, sulky fellow.

*

‘Amma, the girl must have run away,’ said Andalamma.

‘Why would she run away?’ Lalitha made sure Padma did not have long hours. There was meat once a week, a sweet twice a week, unlimited rice. And for company, she was allowed visits from her cousin, who worked for the Brahmin family next door.

‘It’s those films, Amma. That girl got funny ideas from some love-film. Without a doubt,’ the cook said, the sagging skin under her arms jiggling as she brandished a half-cut drumstick, ‘without a single doubt, she ran away with a man.’

‘But whom?’

‘The same one you are thinking of,’ the old woman leaned in and whispered with a nod. ‘The milkman’s son. I’ve always suspected.’

*

It was teatime. The children were playing in the front garden. Peering over the balcony, Lalitha smiled as her daughter, the eleven-year-old, shouted over a ball-game victory against her two younger brothers. Lalitha handed her husband his teacup and called down to the children to play quietly. Padma, if she had not disappeared, would have made sure there were no loud shouts to disturb teatime.

At teatime, the day began to turn. The sun began to mellow. Sea breezes blew hints of salt-water and the scent of temple flowers wafted in from the garden. Teatime was when, after his post-lunch sleep, her husband’s attentions became affectionate. It was when they discussed the storage and care and distribution of the much-praised fruits from their orchards, mangoes in the summer and custard apples in the winter. This was when she recounted the highlights of her day: the antics of the children, the transgressions of the various servants, the adulterating grocers, gossip about who was getting married and with what dowry, and who had yet another daughter.

Sitting with her husband on the balcony, their knees almost touching, a flowery plate of arrowroot biscuits between them, Lalitha thought it a shame to spoil everything by sharing the bad news. When she finally told him, he shook his head and put down his teacup.

‘Girls don’t just disappear, something must have happened to her.’

‘Well, the cook is sure the girl has run away with the milkman’s son.’

Her husband snorted. ‘That scrawny fellow looks like he can barely convince his buffalo to follow him, let alone a girl.’

‘The boy did not turn up today.’

‘That does sound suspicious.’ He broke an arrowroot biscuit in half. ‘Maybe they planned it.’

‘What a fox that girl is! She must have been waiting for me to send her to the market to meet him.’ Lalitha crossed her legs and leaned back. ‘Well, I suppose, if the girl was already planning to run away with the boy, this is hardly my fault.’

‘Lower classes and film stars have the same kind of morals. It is not anyone’s fault.’

Husband and wife sipped their tea.

‘Lalitha, aren’t the girl and boy from different castes?’

‘He is a Yadav and she is a Kapu.’

‘Better not tell her family the news yet. In fact, tell everyone she got lost and returned this morning.’

‘True. Why spoil her reputation unnecessarily?’

‘I will ask the manager to look for her. Discreetly.’ Her husband finished his tea in one gulp and called for the manager.

*

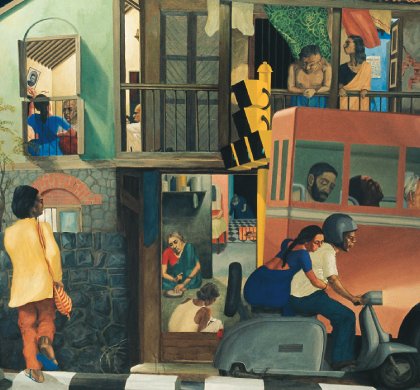

Lalitha hesitated at the back door of the kitchen. Beyond this point, was the servants’ area. First, there was the long and narrow open-air corridor and this was the centre of the servants’ lives. This was where they washed dishes and clothes and had their tea and meals. This was where they exchanged gossip and entertained visiting servants and drivers and workmen. At the end of this space, which now lay empty, was the servants’ quarters: two rooms, a toilet and a bathing area, all of which were built into the compound wall in the back. Lalitha had been there only once, when Andalamma had been gravely ill some years before. Even then, she had felt a faint distaste being in the servants’ space.

In Padma’s quarters, Andalamma began to take the girl’s things down for Lalitha to examine. On the top shelf were toiletries: a comb, a bar of red soap, Nycil prickly heat powder, and coconut oil for the hair. Hidden behind five sets of clothes was a Bournvita tin. Lalitha shook it; it was empty. On the shelf below were two salvaged chocolate boxes filled with fancy store items: bangles, a hair band, two wildly colourful hair clips, and one old set of unused jewelled bottus in various colours. A worn plastic shopping bag held colour pencils, a pen, an eraser worn to a tiny stub, and an old diary Lalitha had thrown away two years ago.

‘What was Padma doing with this? The girl can barely read, let alone write.’ Lalitha opened the old book. On each page was a photograph or picture carefully cut from newspapers or magazines. On each adjacent page, Padma had painstakingly copied the picture. Lalitha flipped through the pages. There were buildings, landscapes, faces, mangoes on branches, roses, pictures of couples staring into each other’s eyes under shady trees, or walking hand in hand in overgrown garden paths.

‘How well she draws! The girl has real talent.’ Lalitha said.

Lalitha lightly ran her fingers around a particularly beautiful drawing of a woman sitting at the edge of a lake of lotus flowers. She imagined Padma sitting alone in this room, sketching these lovely, useless things, only to keep them ferreted away from the world. How had Lalitha not understood this essential truth about a simple child-woman whom she saw and spoke to everyday, who lived in her house? She closed the book and pressed it down on her lap.

Lalitha remembered the musky early morning scent of her children’s hair. She thought of the heat of her husband’s touch, the salt of his skin during their nights of love-making. But what did it mean to caress someone, to speak and laugh and cry with them when there were always unseen veils and curtains in between? Perhaps this was how all people were: closed and unknowable. She wished, in this instant, that she could appear before everyone in her life and ask them what she meant to them. Lalitha stared out the window into a small vegetable garden, enclosed by a grey wall.

‘Amma, are you all right?’ Anadalamma asked.

Lalitha nodded. ‘Did you find anything?’

‘This was on the ground, Amma.’ Andalamma handed Lalitha a slightly rumpled newspaper clipping.

The clipping described a fire that had taken place a couple of weeks ago, on the road that housed the building of the God-woman, Kanaka Durga. The fire had destroyed two dried fruits stores, a medical store, and a tailor shop, but the God-woman’s ashram had been left untouched. The paper declared it a miracle, providing a photograph as proof. Lalitha noticed that a fancy goods store and a sweet shop had not been burnt, but that these were not added in the miraculous pronouncement. The street name and directions had been underlined twice.

‘So, the girl and boy must have gone to seek the God-woman’s guidance,’ Lalitha said.

‘Bad enough she has run away, Amma. Now she wants guidance? Has she no shame?’

Lalitha found she could not muster the moral outrage she ought to feel. Her friends and cousins had all harboured romantic visions of their arranged marriages to future husbands, though not one had actually fallen in love before marriage, let alone been plucked quite so boldly from her house.

Lalitha opened the diary again. She gazed at a picture of a man and woman, holding hands. She let out a soft breath as she remembered the boy’s bony hands. His were not the hands of a man who could defend an inter-caste marriage against the world.

Let the couple escape, she silently prayed. Lord Krishna, the prince of lovers, let them not be caught.

But Lord Krishna should not have to do it all.

‘Andalamma,’ Lalitha said. ‘Ask the driver to get the car ready.’

‘Where should I say we are going, Amma?’

‘We are going to the God-woman, Kanaka Durga.’

*

The God-woman had big teeth in a broad face, and her wide, child-like eyes seemed to sear into the depths of Lalitha’s mind. No one could say Kanaka Durga’s face was beautiful, but Lalitha found she could not look away.

The God-woman sat cross-legged on a large lotus-shaped pink cushion, a voluminous saffron robe gathered loosely around her thin frame. Her forehead was smeared with lines of turmeric and ash, and at its centre was an enormous red bottu. The God-woman glanced at Lalitha, then shut her eyes and joined her thumb and index finger in the mudra of self-knowledge.

Lalitha shifted in her seat. Who was this God-woman? People said she arrived here five years before – where from, no one knew – and had quickly garnered a name for herself among the people of their costal town. Lalitha’s husband often declared that all God-men, God-women, and Gurus were fakes, thieving rascals, bloody fools, pus-boils of Indian society, and spiders draining the life-blood of reason from hapless followers of enfeebling superstitions. These people had no place, no place at all, in a modern, independent India. Lalitha stared down at her twisting hands.

After a long silence, the God-woman said, ‘What do you want? How can I help you? How can I guide you? But I cannot. I cannot help you.’

Lalitha hardly heard the words, she wanted only to listen to voice, the low, husky voice, smooth as water on pebbles. She shook herself. What if the God-woman was trying to hypnotise her? Lalitha’s hand-twisting became frantic. She looked for Andalmma, who stood at the opposite end of the hall, beyond the theatre-style seats and walls lined with pictures of various Devis.

The God-woman said, ‘Did you hear me? You are seeking the wrong person. Look elsewhere.’

Lalitha’s head sprang up. ‘How did you know I was looking for someone? How did you know I expected to find her here, in this ashram?’

The God-woman began to rock softly and Lalitha wondered if she was going into a trance.

‘Kanakamma, you are so right,’ Lalitha said, bowing slightly. ‘I am seeking the wrong person. I can’t believe I did not think of it – it’s not my servant-girl, Padma, I should be seeking, it’s the milkman’s son. He has to be the brains behind it.’

‘Milkman’s son?’

‘But where to find the milkman’s son?’

The God-woman inhaled deeply. ‘I see you will not leave without some answer. Fine. Listen to me: what you seek is pure, no one can give it to you.’

‘Yes, Amma! You are so right! The boy, like his father before him, never gives us pure milk, though I have been seeking it for years. They mix water, and God only knows what kind of water. Chee!’

‘Again, milk? Can’t you think of anything other than milk and milkmen? What you seek is right here.’ The God-woman slowly brought her right hand to the top of her chest. ‘Right here.’

Lalitha also placed a hand, slowly on her chest. She could feel nothing. ‘Is it a necklace, Kankamma? I’ve heard of the rings that holy men conjure from thin air, but I’ve never heard of a necklace being conjured.’

‘Necklace? No, no. Listen! Listen carefully.’

Lalitha leaned closer.

‘Everything you are now talking about is on the outside. What you really seek,’ the God-woman said, patting her chest again, ‘is in your heart. Self-knowledge. Look no further: the search begins and ends within.’

That voice, that voice! It poured over Lalitha like warm, scented oil. It made her believe that she could reach for better things, that she could be kinder, more discerning, wiser. The feeling she had experienced in Padma’s room – that suffocating certainty of the inconsequentiality and futility of all the moments and events and relationships in her life – seemed to fade away and everything seemed to point to this moment, this woman, these words. Lalitha wondered again if she was being hypnotised. Well, so what if she was?

‘Tell me what to do, Kanakamma. Tell me what I should be looking for. Tell me how to find it.’

The God-woman raised her palm in the mudra of compassion. ‘Pray!’

‘Yes, Kanakamma. Pray to whom?’

‘Pray to the Devi. Everyday write the Lalitha Sahasranama and She will bestow Her many blessings upon you. She will answer all your questions. She will show you your karma.’

‘Yes, Yes! I will do it! I will start today, Kankamma. How long should I write?’

‘Keep writing, keep writing! Write with your heart. The Devi will lead you to the answers to the most difficult questions,’ the God-woman said. When she rose, all the attendees stood up. Heads bowed, they followed the God-woman out of the room.

*

That evening, as Lalitha wrote the mantra at her husband’s desk in their room, the cook barged in.

‘Amma,’ Anadalamma said, ‘was it Poured-Milk Spinach that you wanted me to make for tonight, or Spinach with Tamarind?

Lalitha’s eyes stayed fixed on her notebook.

‘Amma?’ The cook shuffled closer and peered over Lalitha’s shoulder.

‘Andalamma, I am busy. Have you no sense of time?’

‘Amma, I have to make the dish, it is getting late.’

‘Abbaah! Fine. Poured-Milk Spinach.’

‘Yes, Amma.’

As the cook left, Lalitha wrote the last two lines of the mantra and waited, pen poised for the Devi’s answers. But nothing happened. Lalitha squeezed, then relaxed the muscles of her hand. Would she see the answer to the question: Where is Padma? Perhaps the Goddess would write out answers to other questions, to the most profound questions. What is the purpose of life? What is the true nature of God? What happens after we die? But the pen stayed stubbornly still. She took a deep breath and waited. If not answers to such difficult questions, Lalitha would have been happy – happier, even – with answers to lesser questions. Has the driver been siphoning petrol from the car tank? How has the milkman been watering down the milk? The pen stayed frozen.

As the watch on her hand ticked on, her mind began to wander. With a start, Lalitha realised that she had forgotten to tell the cook to use four bunches of spinach not three, and six cloves of garlic instead of four. Before she knew it, the pen began to write: Spinach, four bunches, Garlic, six cloves…

After the recipe for Poured-Milk Spinach was written out in full, Lalitha stared for a long time at page. Slowly, she closed the notebook. She put it in the Pooja room, before the photo of Parvathi Devi, seated fearfully on a tiger.

*

Fate decided the girl would return close to midnight. From her bedroom window, Lalitha spied Padma’s small frame silhouetted in the light of the full moon as she stood on tiptoe to open the iron-grilled front gate. Lalitha hurried outside.

‘Girl, is that you?’

Andalamma who had been sitting on the front steps, struggled to her feet. ‘It is her, Amma! She’s back, she’s safe! Let me get my hands on her, that good-for-nothing girl. She’s back!’

Padma entered, her arms dangling as if they were bags she did not where to place. Her shoulders drooped, her smile was tired, but she seemed unhurt.

‘Are you okay?’ Lalitha asked.

‘Where have you been?’ Andalamma demanded.

Padma blinked rapidly.

‘What happened, Padma. Tell me child.’ Lalitha searched for signs of the other, secret Padma, the Padma of the book of drawings.

‘Nothing happened. I got lost, now I am back.’

‘I will not scold you. Tell me everything.’ Lalitha put her hands on the girl’s shoulders. ‘You see, now I understand!’

‘I got lost, now I am back.’

Lalitha dropped her hands. Perhaps there was no secret Padma, after all. Perhaps there was just this Padma: this dim-witted servant-girl with her vacuous-bovine expression, sing-song voice and squat figure. Even the girl’s eyes – almond eyes, flecked with honeyed lights – annoyed Lalitha because, well what were those eyes doing amongst those toad-like features?

‘Padma, enough!’ Lalitha blurted. ‘You can stop the acting. We already know about the milkman’s son.’

‘The milkman’s son?’

‘We know you tried to run away with him.’

‘Amma!’ Padma eyes wide eyes widened even more. ‘I did not. I did not.’

‘Then why did you go to see God-woman Kanaka Durga?’

‘God-woman? Amma, I have never seen the God-woman. I did not run away. I got lost, now I am back.’

And all of Lalitha’s questions and Andalamma’s threats were met with the same recitation.

*

The milkman’s son turned up the next day at his usual time. With a vehement shaking of his head, he denied any involvement with Padma or her disappearance. He claimed his own absence the previous day was accidental. He had spent the day in a ditch. He had tumbled into it while chasing his runaway buffalo.

Lalitha scoffed. ‘Couldn’t you come up with a better story than that?’

‘It’s the truth, Amma.’

‘I suppose it’s ridiculous enough to be true.’

*

‘Padma has been behaving strangely lately,’ Lalitha said to her husband.

‘Who?’ He was engrossed in a Reader’s Digest magazine.

‘The servant girl who disappeared a week ago and came back.’

‘Is she doing her work properly?’

‘She is always cleaning, dusting, sorting. At night, she does not leave even a teaspoon unwashed. In the morning, she is up before everyone.’

‘Then what’s the problem?’

‘She doesn’t say even a word! I wonder what happened to make her change so much.’

‘Please find out. Then we can send all our servants to where she went. And our farmhands. And the manager also.’ He began to laugh.

Lalitha shot him a look of irritation.

‘Look, Lalitha. Isn’t this how servant-girls are supposed to be: hardworking and unseen?’

Lalitha nodded. ‘Still, I wonder what is going on in that girl’s head.’

‘The simple solution is to stop wondering.’

‘Did I tell you, the girl has an old diary? She has drawn some beautiful pictures in it.’

He did not look up from his reading.

‘I saw it in her room the day she disappeared. I wonder what inspired her to start drawing.’

‘Why don’t you ask her?’ He said, as he turned a page.

‘I’ve wanted to ask her about it, but, I don’t want to admit that I’ve seen the book and looked through her things. Anyway, I suppose it’s just as well. One should not show too much interest in the affairs of servants.’

*

The news could not be hushed up for long. Two weeks later, Padma’s father rushed into town.

‘Amma! I will break his legs. That fellow first seduces my daughter, and now he tries to discard her! Tell me Amma, who will marry her now? What will happen to her life? That scoundrel must marry my daughter.’

‘He will not agree. I can tell you that for sure.’

‘You must help me, Amma. You must help me.’

Lalitha looked down at the grey and black flecks of the mosaic flooring. The front verandah remained cool despite the late morning heat that baked the mud floor of the front garden. Padma leaned against a cement pillar and stared at the ground while her father paced near another pillar. Dust caked the silk cotton tree and the parijat plants behind them. Lalitha wiped the sweat off her face with the pallu of her cotton sari.

You must help me. It was a powerful phrase and a reminder that Lalitha bore some responsibility for the girl he entrusted to her care many years ago. Padma’s father came from her husband’s ancestral village and many of his relatives worked as her husband’s farmhands. Lalitha knew where her loyalties lay.

‘Without a doubt,’ she said, ‘I would do anything to save the girl’s honour. But they both deny having any relationship.’

‘They both disappeared at the same time, Amma. I promise you, they are lying! He must marry her.’

‘You do know that he is from a lower caste.’

‘What choice do we have? A woman’s virtue is like an eggshell. Once broken, nothing can put it back together.’

*

The milkman’s son leaned against the pillar that had supported Padma just a while before. His hands gripped the top of his head.

He began to plead, ‘Amma, you tell that man, I will not marry his daughter. I attempted tenth class. She can barely read and write. I will never marry her.’

‘Shut up, you scoundrel!’ Padma’s father shouted. ‘You should fall to the ground and thank the gods you have this opportunity to marry into a high-caste, land-owning family. If it were not for your good luck and my terrible karma, this marriage would have happened only over my dead body.’

‘I refuse to talk to that man, Amma. What land-owning? He has two and a half acres of land that can only grow rocks. With my qualifications, I can get jobs. I get respect. Anyway, I did nothing wrong. That day, I had only been lying in a ditch. Who knows who his daughter ran off with!’

‘Talk about her like that again, and I’ll wring your neck. What is the proof you were in a ditch? Did anyone see you?’

When the milkman’s son could produce no witnesses, the father dragged both the boy and the girl to the police station.

*

When they returned to the house, the boy and girl had frayed marigold garlands around their necks. Finger-thick kumkum marks reddened their foreheads. Padma fidgeted with her garland, eyes fixed on the ground. The milkman stared sullenly to one side.

Things had worked out, Padma’s father said. The police had, under humanitarian grounds, threatened the milkman with arrest and a sound beating for spoiling a girl’s honour, and had gotten the young couple married in a local temple. Afterwards, the three of them had gone to the boy’s house where Padma’s father had offered the milkman’s family his daughter’s savings from all her years of work and two milch cows as dowry. It was agreed that the bridegroom would move in with Padma’s family in the village, as they had no son to care for their land. They were to leave in two days.

Lalitha selected five of her silk saris for the girl’s trousseau. She bought a necklace of black beads and gold from the family jeweller. She gave the girl two old stainless steel dishes and a big bag in which to carry everything. She felt oddly teary, as if her own daughter was leaving.

*

The next day, when Andalamma went to Padma’s old room, she found the diary. The girl had left it on the shelf, though she had taken everything else, even the empty Bournvita tin.

*

‘Lalitha, how serious you look.’ Her husband yawned, having woken early from his afternoon sleep.

Lalitha did not look up from her notebook. Every day, she wrote the Lalitha Sahasranama, and when she reached the end, the pen wrote one recipe. She wrote in the quiet of the afternoon, while the whole household rested after lunch. Sometimes the pen wrote the recipe for a dish that was made that day and sometimes it wrote a long-forgotten one, and this revived its place in their household.

‘What are you writing so diligently there?’ Her husband came up behind her and began to stroke her neck.

‘Nothing important.’ Lalitha shrugged away his hand. He had no other work, or what, than to make advances in the middle of the day when anyone could walk in?

‘What is so much more interesting than me?’ He peered over her shoulder. ‘Dried shrimp. And coconut.’

‘It’s just a recipe. I write one every day.’

‘Why?’

‘Just like that.’

‘It can’t be just like that. Something or someone made you start.’

Lalitha dropped her pen. ‘Why do you say that? No one made me start! No one.’

‘Some urge must have been there, then. Maybe, secretly, you want to be writer.’

‘I’m a half-educated woman from the mofussils. How can I be a writer?’

He straightened. ‘This is modern India, you can be anything.’

‘Don’t start on this modern India business, or you’ll go on for hours. Let it be.’

‘I won’t let it be. I am going to Madras tomorrow, and I will ask my cousin Ganesh to talk to his publisher friend. Maybe he will have your recipes published as a cookbook. After all, in this great, rising nation,’ he said, sweeping his arms up like a great nation rising, ‘we now have a woman prime minister. We have women soldiers and doctors, why can’t you can have your own book?’

Lalitha smiled. She closed her notebook and rose slowly.

‘Do you think you should lock the door?’ She wound her arms around his neck.

‘Oh! You are being very bold,’ he said.

‘In modern India, women can be bold.’

*

Lalitha thought no one could possibly be interested in her cookbook. Every mother-in-law passed down age-old household recipes to her troop of daughters-in-law, so generations of men could remain in the comfort of knowing exactly how each dish would taste, even the before first bite. Who wanted new recipes?

But daughters-in-law bought the book because they were curious. Someone like them, a regular housewife, had written it and published it and had become famous. Mothers-in-law bought it because they were reassured by the familiarity of the recipes, yet were charmed by the small and intriguing differences. Of course, it was only by the grace of Lord Ramakrishna that the book became a bestseller and was reprinted in Tamil, Kannada, and Marathi.

Lalitha wanted to give a copy of the book to the enigmatic God-woman. But Kanaka Durga had disappeared the night Padma returned and no one had seen her or heard of her since. Lalitha wondered at it: the night the girl came back, the God-woman disappeared. Perhaps this was how karma worked, in a circle.

*

The children had left to school. Andalamma sat on the steps of the front verandah, picking out stones from rice grains. Lalitha settled into a long cane chair in a shady corner of the verandah. She needed to revise the Badam Kheer recipe, an almond milk-sweet that her sons adored. She had begun her third cookbook, a book of sugary snacks and desserts. She called it, ‘A Sweet Life’. Her cookbooks now included short descriptions, deftly crafted by Lalitha’s daughter, who had acquired aspirations to work as a writer for Illustrated Weekly magazine.

Just as she finished the recipe, the gate creaked open. It was Padma. Lalitha put down her pen. She felt as if five years had flown backwards, as if the girl had just returned from her disappearance. Andalamma immediately demanded to know why the girl had not visited before. Padma shyly shook her head. She walked the same way, hands dangling beside her as if she did not know what to do with them.

All was well, Padma said. She now had three children, two girls and, finally, a year ago, a boy. But Lalitha knew there was more to the story. Last year, when the rains failed and the earth lay cracked like snakeskin, Padma’s family had fallen into debt. They had failed to make their payments and interest upon interest ballooned their loan. The milkman’s son was driven to drink and his health deteriorated. It was said that he now spent most of his day on the cot under the mango tree while Padma and her parents worked the fields, ploughing and coaxing the unyielding earth.

The sun and hard labour had aged Padma. Lines that would, in a few years, sculpt themselves into her forehead already showed faint traces. The slight cushioning of girlhood had sunk out of her cheeks, her arms. Her sari was faded and her hair was tightly braided and tied with a plain, black rubber band. Lalitha thought of the fancy store items she had seen in Padma’s room: the jewelled bottus, the coloured hair clips.

‘Child, you must be hungry. Have some lunch,’ Lalitha said.

‘Come. You can eat from your old plate.’ Andalamma took the girl’s elbow.

Lalitha waved them towards the kitchen. ‘Andalamma, give her some of the chicken curry. Give her the jaggery sweet from yesterday.’

It was early evening when the girl said she had to leave.

‘One last thing,’ Lalitha said, handing Padma the diary. ‘Do you remember this book? Andalamma found it in your room the day you disappeared.’

‘I don’t know anything about it, Amma.’ Padma handed it back, her expressionless gaze fixed on the book.

Lalitha thrust it upon her again. ‘See. Open the book and see. Maybe you will remember.’

Padma let the pages fall open at random. There was the picture of a rose. She turned the page. There was one of hills against a sky. Lalitha imagined the girl sharpening her pencil, outlining those hills, shading that sky: Padma, burrowed in her art during secret hours, her eyes and hands searching beyond the reaches of her life.

The girl turned the page again. ‘Amma, what do I know of all this? All I know is to scrub floors and wash the dishes.’

‘If it’s not yours, and it’s not mine, whose is it?’

‘I don’t know.’ Padma stared at the drawing of a couple under a tree.

‘Well, what should I do with it?’

‘What can I say, Amma? You know more than me.’ Padma turned to the drawing of the woman at the lake of lotus flowers, her fingers gliding slowly over the woman’s long hair, over each flower. She shut the book and Andalamma took it from her.

‘Maybe, Amma,’ said the old cook, ‘we can sell the book to the trash-man in the corner of the lane. We can get a few paise for it.’

Lalitha imagined the trash-man taking it, selling it to the vendor of roadside snacks, who would tear out a page, perhaps the one bearing the drawing of the woman at the lotus pond. She pictured him wrapping masala channas in it, the oil and spices soaking into the drawing and finally, the paper being crushed into a ball and thrown on the side of the road.

Lalitha said, ‘Sell it? Like trash?’

Padma stared at her feet, her front teeth pressing at her lower lip.

‘Amma, I should go before it becomes dark,’ she said, finally.

As Padma closed the gate behind her, she was joined by her next-door cousin. Before long, the washerwoman came passing by and greeted them, and then the sweeper-woman. As the women began to chat, the evening light shone on their angular arms, their long braids kept in place with oil, their faded saris draped on frayed cotton blouses, their straight, hard backs indented with chiselled backbones, and their scorched skin.

As they walked away together, Lalitha could not tell who was who. She could not tell them apart.