You Should Never Be Here Too Much

Bhala hua meri matki phuti

Mai panya bharan se chuti

Moray sar se tali bala

Fortunate I am that my clay pot cracked

I no longer need to fill it with water

I have been freed of worthless worries

Kabeer

translation by N. Gandhi

What do you think life’s all about? She asked.

For most people life is about getting by, her friend said.

*

She hurried to the staff meeting. She was unpardonably late. Dozed off after lunch. Who does that? She couldn’t believe it. Dozed off! It was not like her. The dry autumnal leaves of patjhar crunched under her feet.

Suddenly, like Alice’s discovery of the rabbit in flight, she saw the tree. It stopped her. She was so stunned by its sudden, enchanting green that she couldn’t move. Last week, she was sure it was just last week that she had seen the same tree. Its branches had been brown and bare.

And now? How could it have changed from brown to such a luscious emerald green? Her mind did a series of somersaults. Was it the same tree?

*

Spring comes, no matter what. Was it Pablo Neruda who said that?

Her inconsequential life, which gives her such a headache, goes on no matter what. This bride-like tree, newly green, its silvery pink leaves glistening in the late afternoon light. The tree, so shy, yet so sure of its place in the cosmos, standing proud, tall and stately, its roots so deep and firmly planted, its many outstretched arms offering what each passer-by would like to take.

This is an act of love, she thought.

Shouldn’t she just sit down underneath it, embrace its multi-branched trunk, and rest her aching back against its solidity? But there was the staff meeting.

Later that evening, back in her room, she felt her depression lift a little. She remembered the nonchalance of the tree, its size and its greenness. She had walked back to the tree after the meeting. She had stopped to look at it calmly. The new leaves seemed darker and denser in the fading evening light. At the base of the trunk she found last year’s leaves.

She felt her awe grow. Even as mulch your leaves have a job to do!

Nearby, a woman stirred a pot over a fire. Behind her, the rusty tin roofs of workers’ dwellings glistened in the slanting light. The woman probably lived in one of them.

Do you know the name of this tree? she asked her.

Pakari, the woman replied without looking at her.

Pakari? It wasn’t so green last week. Was it? It happened suddenly.

Pakari, the woman replied. She stared resolutely into the contents of her pot, as if resenting the intrusion into her solitude.

Pakari, she repeated after the woman.

You’re lovely! She addressed the tree in silence. How old are you? Look at your huge trunk. It’s like you have so many trunks. And you put on this show every spring! I want to be you in my next life.

A bird she couldn’t see high up in the tree was trilling with all the strength in its body. Twee-twee-twee-twee went its song of freedom, rising above the din of the traffic and the roar of the train passing by on the distant bridge.

*

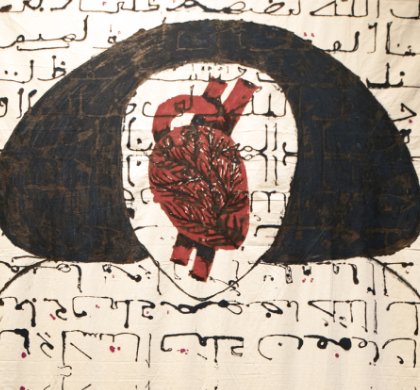

We all want to be free. We are in love with the state of liberation. She opened the book she was reading. It was an old gift from a friend of hers with whom she had worked in the university library when she was a student. But finding freedom is not for the timid. It requires courage and a sense of adventure, a fearless heart. She went on reading. Then she put the book down.

A fearless heart?

Courage?

The spirit of adventure?

Do I have all this? Do I really want to be free?

She should have taken the path of the faqeeri long ago if she wanted freedom. But with such a heavy heart to carry around with her, she couldn’t do that. She had to get rid of all the extra baggage, the doubts, the regrets and all those nagging fears. She had to be ready to bounce through life like a cloud without a care in the world. Or be steady like the Pakari tree. Simplify her desires. Empty her heart. And allow it to be filled with nothing much.

But even the desire to be a faqeer is a desire, after all?

*

She’s walking with her husband. She has decided to visit him this weekend. She’s accompanied him on his evening walk to tell him she’s decided to leave The Arrangement. Formally, that is. At dusk, when they were walking side by side and neither could see the other, it was easier to tell him. The Arrangement has lasted a long time. Some days she thinks she’s been heroic to stay in The Arrangement for so long. Other days she thinks she’s been a complete coward.

I have decided to … leave.

Where will you go?

I have no idea. It’s a big planet.

Nothing more was said. They walked on until they reached the turnstile, under the ominous, low-slung branches of the park’s ancient Jinn-like trees.

Finally, her husband spoke.

The ice trays are encrusted with salt. They’re getting pretty old. I’m going to get some new ones from the USA this summer.

Did you not hear what I just said? I don’t give a damn about the ice trays. I’ve wasted my life. This fucking arrangement. This city. Your career. And you speak of new ice trays!

Right there in the park, she wanted to scream and sob and say a lot more. On the other hand, she also wanted to sound very distant, rational, and unemotional. So she said absolutely nothing. They walked in silence the rest of the way to the car park.

Why didn’t she scream and say all the things that she had wanted to say? Hadn’t she said all of it before? Countless times?

That night, as she lay on her side of the bed, with the middle of the bed as empty as a mown field between them, she thought: I said the whole planet was my home. Foolish! Childish! My longing is for faqeeri. While my existence is rooted in The Arrangement, how in the hell can I hope to break free of it? Disentangle myself from The Arrangement?

*

She wasn’t sure if she would ever be able to untangle herself. Unlike the newly appointed physics teacher, her new flatmate, who had moved in over the weekend. He came out of his room to introduce himself.

He said: All I need is a bookcase for my books. I don’t need much. Not even a bed. I can sleep on the floor with a pillow under my head.

You’re so courageous. I need a lot of things, she said as she entered the kitchen.

He started to talk more. Could it have been because of her affirmation? She must have conveyed her willingness to listen by listening. He told her that he had a doctorate. But his father and brother had put him in an asylum because he had tried to speak up when his father was beating his mother.

It was a cross between an incompetent hospital and an inhuman prison, that place, he said.

I can’t imagine what it must have been like for you to have been there, she said in sympathy.

I escaped after a year … somehow.

Good for you!

She watched the pot of water boiling on the stove, and he watched her.

Are you boiling water for coffee?

I am. Would you like some?

No, no. Please go on, I was just asking, he said, and hurried back to his room.

But when she brought him a cup of coffee and knocked on his door, he eagerly accepted it. He thanked her several times.

He may not need a bed. But he does need coffee and conversation! And I am in need of a lot more than that, she thought dismissively. I’m neither here nor there. I’m this in-between person. It may not be a whole lot more, but I certainly need lot more things than he does. Bed, coffee, chocolate, books, bookcases, clothes, laptop, laptop charger, phone, pens, paper, blankets. And love.

*

She called her friend, who also acted as her therapist, to tell her about the amazing Pakari Tree and how it had suddenly turned green. Then she moved on to what it was she really wanted to tell her.

I was home last weekend. Can’t really call it home anymore! I said, listen, I can no longer be the sweet, intelligent but not too intelligent wife. I can’t go around swapping recipes with other wives. I can’t put up with all the good-natured flirting from their husbands. I can’t have dinner parties anymore. I can’t go on pretending to be normal. She didn’t tell the friend that she hadn’t actually said those things.

You said all that? Congratulations!

No. Well, I just … basically … said I was leaving The Arrangement.

In a world of fugitives, the person who goes in the opposite direction seems to be running away. T S Eliot. In a world of fugitives, my dear, you’re trying to run in the opposite direction. It’s not going to be easy.

I’ve been doing that for a long time, she said. I want to run in the opposite direction and yet I waver. Again, she remembered the Pakari tree. She asked her friend about the possibility of what she herself didn’t believe was possible. What would you choose to be in your next life? If there is one?

A bird. A free bird, a bird that flies where my heart desires. And you?

I would love to be a great old …

Whale?

This made her laugh. Not a whale! I won’t be able to cope with the annual Hijrat I would have to make. No. I’ll be a big tree. A big old Pakari tree. I’ll stay in my place no matter what happens. I’ll burst into leaf every spring.

Then I can visit you. I can sit on one of your branches, the friend said.

You could build your nest in one of my branches?

I’m not the nest-building type.

Of course not! I forgot! Ms. Azad.

*

That night she lay awake in bed. It began to rain. Thunder rolled. A damp, gentle breeze blew in through the window. She had deliberately left it open. She lay in the coolness of the rain. She listened to the big drops, imagining them falling and disappearing into the hungry earth. Breathing in the scent of rain coming from the swollen earth outside, she began to relax. It was late when she finally fell asleep. When she awoke for work a couple of hours later, her eyelids weren’t burning and she had no desire for more sleep.

She felt rested by the night’s rain.

New arrangements require a ruthless simplicity of purpose and practice, she instructed herself. She undressed and stepped into the shower. I must stop at the pakari tree to pay her my respects. To ask her how I can let go of the settled life … the need for a home and belonging … all such traps. How to find comfort and refuge in the sacredness and stillness of myself … No place like me!

How will I get there? How am I going to get by with so much less of everything? A lifetime has passed, a wasted lifetime. The Earth has spun God knows how many orbits around the Sun, and I’m still trying to fathom what it is that I need to shed.

Stop thinking! she said to herself as she stepped out of the bathroom. She was naked and suddenly she had a desire to lie naked on the cool, bare floor.

Will I ever find out?

Yes!

She wasn’t sure who it was who said yes.

The title of the story is taken from Krishnamurti’s Notebook by J Krishnamurti.