Until It Beats

Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and fifty-seven.

Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and fifty-eight.

Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and fifty-nine.

This is getting rather tiresome. I wonder how long I have been counting.

Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and fifty … oh wait, that should be twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and sixty.

Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and sixty.

Yes, yes, that’s it. Roughly divide twenty-nine thousand seven hundred and sixty by six, six fives are thirty, so six fours are twenty-four … four hundred and ninety-six minutes.

Has it been over eight hours already? Maulana sahib would have been proud. Titli has finally learnt her six times tables, eh? he would say. Mental division too!

Oh, I have lost track of where I was. This has always been my problem, thinking faster than I can keep pace, always lost in peripatetic ruminations. Maybe I should start from the beginning. But I’ve come so far! Twenty-nine thousand something … starting again would be a stretch.

Oh look, daybreak! At last, it is here!

You see, I have contrived a method to demarcate the hours, discern dawn from noon, twilight from dusk, and subsequently, the nights. It is a rather recent breakthrough really, though I cannot say how long I have been here. The initial period is a haze.

The last distinct memory that my mind can summon is the taste of chai. Ammi had brewed a steaming cup for Abbu, who had been seated across the table from me. I remember watching him sift through some papers, softly mumbling about the fatuous ways of the government. When he wasn’t looking, I swiftly stole a sip from his cup. He didn’t approve of me drinking chai just yet, Chutki, you’ll become dark, kaali, he would have reprimanded, had he caught me in the act. But he didn’t.

I wonder what Abbu and Ammi are doing now. Do they miss me?

See, I am digressing again. Where was I? The breakthrough, yes.

While I was nurturing my latest hobby, that is counting, it struck me out of the blue.

Even before I heard the throaty grumble of the industrial machinery, I would feel it – the vibrations – through the ground, gravel and sand trembling against the back of my thighs and hips. Gradually, it would get louder, and louder still until I could no longer concentrate on my numbers. It would annex my capacity to think.

Shortly thereafter, the door would creak open and metal would skid across the room, sending my skin crawling. Metal on stone and chalk on board – they give me the worst goosebumps. I hate the sickening pit in my stomach they incite, the urge to regurgitate my insides. How I hear it every day over the monstrous roar of the machines is still a mystery, but at this point, I should probably stop questioning such things. It is that unpleasant sound I have come to associate with my first meal of the day.

Right now, the door is creaking open. I can hear it.

I was right, it is morning!

A diminutive ray of light flits through the gap between the hinges. I glimpse a hand. The man tosses the plate in the general direction of the room and in a flash, darkness reclaims the space.

I can hear the plate swivelling a little farther away. I have ample time to crawl, the next visit will not be anytime soon, I know. But I am rather tired. Is stale bread worth all the effort? Perhaps they have felt kindly enough to fetch pooris this morning, like they did once before.

Whatever it may be, I must eat. Ammi says declining food is akin to declining the will to live.

When I was a toddler, I was quite the fussy eater. I had the nose of a rodent, apparently. I would purse my lips and hide under a couch to avoid being force-fed. Ammi and Abbu indulged my tantrums first, coaxing me out from under and inventing games to make me eat. As time passed, Abbu grew tired of my tactics. Someday it will hit her, he would say.

I drag myself slowly across the room, scrabbling at the surrounding areas as I go. The plate turns out to be closer than I had imagined.

Stale bread.

*

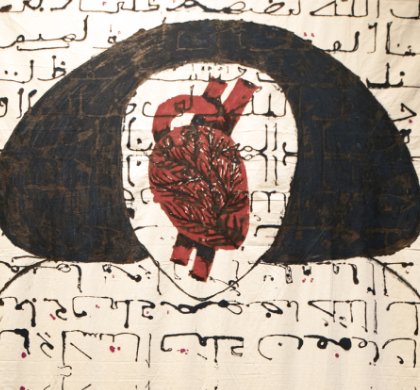

Titli, Titli, you’re a butterfly

Your heart is your wing,

The world is your sky.

Until the beat is unremitting

You must continue to soar high,

For you, Titli, are a butterfly.

I wake up with a start. I must have fallen asleep. The faint ring of the lullaby still echoes in my ears, even though logic dictates that it was a dream. All we are is but a dream, no?

The quiet is diffusing with the darkness, so much so that I cannot tell them apart. Perhaps it is noon. The machines are taking their brief hiatus.

My heart is pounding against my ribs. Thud. Thud thud. The silence is making it sonorous; I can hear it beat. Thud. Thud thud. Sometimes, I fancy that the sound travels all the way to the city but is lost in the maelstrom of city life. It is quite the amusing story really, about how the heartbeat steals past the factory floor, avoids being trampled on by large boots, rides the wind into the city and battles flapping insect wings, but eventually vanishes down a drain. Maybe I’ll narrate it to you some other day. I still have to add some flourishes to the plotline.

I like indulging my thoughts. There is only so much you can do in a room by yourself. At first, I remember I used to be too afraid and too disoriented to do much but cry until I passed out from exhaustion. I would wake up, in the pitch dark and weep all over again until the machines stopped groaning.

Eventually though, I gave up on crying. There was no point to it, honestly. It riled me up while draining me of all the energy I possessed.

Instead, I began to revive my habit of chewing on the sides of my fingernails. The rusty tang of blood and dull distress around the edges comforted me, just like all the times before exams at school. The physical sensation lent an almost meditative passivity to the chewing.

When I had exhausted all the dead skin I could ingest, I would try to haul myself off the floor to try and walk, but I would be too sore to do that.

How long has it been since I was up on my feet? I mustn’t try too much, it makes my head pound.

I can feel something crawl up my leg now, a spider I reckon. I let it be. There have been worse things slinking up there.

It reminds me of a story I once read, about spiders in arid regions. It spoke of this one species where the young feed on their mother’s corpse as soon as they are born. It glorified the sacrificial nature of motherhood. It never made much sense to me, perhaps because

because I don’t know what it feels like to be a mother?

A sudden jab knifes my insides just as the machines begin to roar again. This happens occasionally, the spasms of pain in my abdomen. I run a hand over my belly to soothe it and shut my eyes tight in an attempt to will it away. I can feel the slight bump of my ribs in my middle.

I begin to hum softly to myself; it is a song I used to hum often on my way to school. Somewhere mid-way through the fifth time, I drift to the park near my house. It is a tiny square inch of decrepit land, just enough to hold five screeching kids, and one adult to supervise. It has one slide in the corner and two swings.

The top of the slide has the best view: you can see four blocks down the road until where the sweetmeats are sold. Ammi look, I can see the whole world from up here, I would say. When you are young, the four blocks around your home is the only world you know, Ammi had said once. I am seated atop the slide, on the shiny seat just about to go down, when someone pushes me before I’m ready.

I slither down the aluminium but never reach the end, keep going on and on and on instead. There are coils and curls as I zoom down, the wind delicious against my skin and hair. I feel like I’m flying. I lift my arms up, but they aren’t arms any longer. They’ve morphed into wings. I flap, flap, flap, but don’t take flight. I don’t mind though. This is good enough. I can go on forever. The trees are a blur of green and the cars melt into a whirlpool of hues, it feels almost like I am riding the rainbow.

I am riding the rainbow.

Now I can see the end of the slide, far ahead. I have a good five hundred metres to go, I think. It opens into a sea of something … hands. I see hands reaching out for me. There are so many of them, large and small, mostly that of men and babies.

Panic bubbles up my throat. No, I don’t want to go. I must make myself stop. I don’t want to go down there.

I’ll just sit here. This is nice.

I try to grip the sides of the slide, but my wings have no clutch. They’re quickening the drop, rather, slithering smoothly along the aluminium. The hands are closer now, fingers crawling up the slide, fists pounding, all reaching up to grab me. If they catch me, I’ll drown.

How do I make it stop? Please, just make it stop. I’m so much closer. I try flailing my wings desperately. The hands are just a few metres from my feet. This is it. I recoil in horror and bite down a yell.

I open my eyes.

I’m curled up in a foetal position against the wall. My stomach squeezes in hunger, I swear I can feel it digesting itself. My heart is beating violently, it distracts me enough to almost miss the open door.

There are just three men today.

It is over rather quickly. They laugh when they are done; one tousles my grimy hair. I, on the other hand, am just grateful for the glass of milk they extend in my direction. It soothes my parched throat. And then, they are gone, shutting the door behind them.

Good.

Only thirty-six thousand heartbeats until breakfast.