Too Long Too Late

In the years of her long childlessness – which lasted only three years – Tara had been in regular touch with her uncle. An uncle who shared her own pitiable status. Everyone she knew then felt childlessness was a curse, a terrible thing to bear, an unbearable torment to shoulder as one went through life. It was a safer world to have children then – no one bothered about climate change or other possibilities of destruction now alarmingly clear. Also no one, not even Tara, knew that one could choose to be childfree, or that one could adopt or even opt for surrogacy. The reasoning was simple: one married, and then one had children. This was it. Life progressed that way; these choices gave life some predictability.

This uncle, Shishir, when she first wanted to contact him, was deemed by everyone in the extended family, her older cousins, for example, to be bonkers. He was eccentric, weird, and moody, and everyone knew why. The real reason, never discussed, never raised between them was that he was childless. It had destroyed his marriage. That was what this state did to one.

Would she become like him, Tara had often wondered? Would her marriage fail, and would she too one day become as cranky and eccentric as him? Isolate herself from the rest of her family like he had done? He had moved to faraway Edmonton in Canada, a place so terribly cold that no one from the family had ever visited. Tara wanted to find out for herself though of course she didn’t want to tell him her real reason.

Tara lived in Bombay then, but even in a cosmopolitan, urban city, modern in every way, there was no putting off people and their questions. Wherever she travelled on work, or whenever she met a relative or even if she had a random conversation with someone, that question would invariably be asked, sooner rather than later. That one question that followed from leading questions, typical and predictable. How old was she? Was she married? How long? And no children yet?

Tara wished she could say that she was confused. That she was ambivalent about a baby, that she wanted to think of her career, but she never could. She felt she’d seem like a monster. A woman who didn’t want a child. Tara wanted to know for herself how the Edmonton uncle – which is how everyone referred to Shishir – had lived through these long years, without children, how he had survived the questions, the curiosity, and, as she admitted, the haunting loneliness and emptiness. Everyone around her was having a baby, she did feel left out.

Shishir spoke too fast the first time she called him, his words rolling out in a musical sing song. Tara pictured him doing a dance jig around his room, his hair balding in front, and the straggly long hair at the back arranged in braids, like ‘rat tails’, as her mother once described them. She thought he even wore dark glasses. Reminded her of Stevie Wonder. Moments after she disconnected, when the call ended, she admitted to not understanding much of what he said.

After they had spoken on the phone three or four more times, she was no longer able to ask him anything. For his answers became a repetitive monologue, as if he was singing a long rap song. He wasn’t an angry man, or even aloof, he had just been misunderstood, he said, over and over again.

It was he who had dropped out of the family. No, no one had abandoned him, she wanted to tell him. He had not attended any marriage in the family after his own, more than thirty years ago. He hadn’t even flown down for the marriage of his younger brothers. It was already understood by then that he was having job trouble and had financial issues.

But there was one thing she did understand. It stopped her interrupting him mid-flow and risking his anger. That thing he could never state. A far more serious matter. That of children.

She knew how it felt. If one was childless, one felt ostracised, left out, isolated, talked about. Not having a child made one a diminished being. It was worse for a woman. Tara understood this very well. It was what made her want to avoid family. She was happy when the chance came soon after for them, her husband and her, to leave Bombay for Singapore.

*

Three years was a long time. After one had been married for three years, one no longer had the luxury to ‘wait’ for children. Three years. After that people began to ask. Questions laced with concern – false and spiteful – and fairly demanding of an answer. How could she not have had a child yet? Had they even tried for a baby? Was something wrong?

At a family wedding in Calcutta, a sister-in-law had been scandalised when she learnt Tara was still childless. Three years. Sister-in-law counted off on her fingers. She raised her voice and screeched this bit of information aloud, drawing the attention of the other women in the circle who thus far had been teasing each other as they sang the old, bawdy wedding songs. Songs about husbands, innuendo-laden, complete with hidden meanings. When sister-in-law spoke, everything, the music, the singing, stopped, and a silence fell. Everyone turned to look at her.

Tara was dressed just like them. It was a family wedding, and she had on an expensive Chanderi sari, and her wedding jewellery. But though she was dressed like them, looked like them, the state of being childless singled her out. Everyone turned and sized her up. She felt their united condemning gaze, coming at her from every side. She saw the way their bosoms swelled with pride, their chins lifted, the gleam of excitement that came into their marriage-and-motherhood dulled eyes.

It frightened Tara. She felt mocked and condemned. But she did not want to become like them, like the women around her, and elsewhere in the family, even those in old sepia-tinted photos hung up on walls or on mantelpieces. Young mothers, beautiful in their early photos, and who, in their forties, were already grandmothers, fat in a matronly way, with that terrible dullness about the eyes.

One by one, all the bright beautiful women who looked so lovely in their photos, in their bridal wear, in the daring clothes they wore, before and after marriage, turned to diminished beings because of childbirth, and care, the responsibilities of motherhood. That stage of life that everyone, especially the older women in the family told her about, the time of life that was the most fulfilling, was something she had to aim for as well, or else she would be incomplete. But such thoughts left her afraid. It was like being sucked into a vacuum. It was a choice between motherhood and nothing. Motherhood versus loneliness, emptiness, isolation and being picked on constantly.

No children, sister-in-law had said, raising three fingers of her hand, and doing the counting thing again. One. Two. Three years of marriage. This is worrying. The singing dwindled down, someone beat on the drum slowly, ominously.

Two years after Tara moved to Singapore with her husband, their daughter was born. And time began moving much too fast. It was hard to keep track of things, of errands, to remember dates and people she had once known. At one time, she had wanted to drop out of circulation, keep away from prying, over-curious, unempathetic friends, and family, but now having another life to manage meant it happened automatically.

When her daughter was two, they moved to a bigger apartment on Singapore’s East Coast Road. Her daughter began going to a play school. Tara had to match her schedule to her daughter’s as best as she could. She didn’t have time to write to anyone. She remembered writing to Shishir soon after her daughter was born. She always thought he had written back to her, most people she knew had messaged, texted, emailed their congratulations then. Everyone had been so happy (so relieved?) for her. Shishir must have written back, but she really wasn’t sure. Time had become a hurricane passing by, sweeping her up, moving on at a stormy pace.

There were occasions, when waiting outside her daughter’s school, those years of childlessness came back to her – had it just been three years? She had endured being universally mocked, and condemned. She had wanted to hide away. Was that all she remembered of that time? So many days, weeks, months of her life gone, evanescent, and fleeting. Her life, those three years, a bit more, reduced to a memory of a mocking sentence, a tortured time, a feeling of being incomplete.

When Tara’s daughter was three, they moved halfway across the world to the United States. It seemed to Tara they were always moving places, forever settling down in new ways and that she had moved from being an ambitious career woman, a childless wife, to being a trailing spouse and expat wife, too soon, too quickly. In Maryland, her husband’s work life kept him busier than ever. For half the month he was travelling out of town.

She often remembered all the people she had to write to, the people she wanted to get back in touch with, the cousins who asked after her, who remembered her birthday, her daughter’s too, and who thought she had forgotten theirs. At times like these, she thought of her uncle, Shishir, in Edmonton. It made her frown, bite her lips, lose patience with herself, and move on. She just couldn’t remember anything about his last email. Nothing about when he had sent it, how he had taken her news, and just how he had congratulated her.

But she did want to email him. To carry on from where they had last left off. She often found herself looking for that last message from Shishir. And always, other things, other demands, things to do with her daughter, got in the way.

After a year in the US, everything still seemed new, too big, and too forbidding. Every day was a small struggle. To fit in, to be understood.

At the café, she wrote for two hours almost every morning after dropping her daughter at school. She picked a table at the very corner and watched people: how they walked, behaved, talked, especially the clothes they wore. Yet it was she who always felt seen and sized up. Every time the barista with the frizzy top of hair looked her way, she felt raw and exposed. Then one day, Megan, the red-haired girl with the big breasts came over to clean her table and smiled. And Tara for the first time felt an odd sense of comfort and relief.

Oh no, you’re fine, Megan said every time Tara gathered up her stuff, to let Megan spray cleaner on the tabletop and wipe it quickly dry, with the roll of paper towel stuffed in her apron. She was there on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and soon Tara looked forward to a chance to talk to her. What thrilled her was the fact that Megan had no trouble figuring out her accent. There was no blankness on Megan’s face, she did not deliberately slow down her own speech, nor did she look at Tara’s lips to figure out her words. Tara remembered the hostile gaze she had drawn from a group of women when she had walked into the club, the place everyone in her apartment block had access to, or the time, the check-out girl at Gap had asked for an ID after she handed over her credit card.

Tara had felt like a suspect in something she could not name. The process of fitting in took a lot of time, just as – though she did not quite make this analogy till many years later – the agony of being childless had once troubled her for a long time.

Sometime after her daughter turned five, Tara looked – more determinedly, and industriously – for Shishir’s last email to her. Was that when she had more time to herself? She did begin reaching out to lost cousins then. She was beginning to feel somewhat confident in her own skin. By then she had a presence in too many places on the internet, and searching for Shishir, in the deluge of messages, posts, comments, she always received, and posted on her own, soon overwhelmed her. She didn’t like how she sounded in her old posts – too saucy, too artificial? – and embarrassed, she dropped her search abruptly.

Two years later, after yet another move, this time to New Jersey, Tara remembered she still had to write to Shishir. She wanted to look for his last message again. How could she have let so many years go? One kept in touch with older relatives, especially someone who had not been too inquisitive, who had been hurt just as she had been, by overcurious, prying relatives. Had she become like the very women she feared – those consumed totally and utterly by motherhood?

She felt guilty. She could imagine Shishir, hunched over his laptop, in a manner quite like hers, his eyes bulbous behind thick glasses, the bald pate shiny in the neon light overhead, chewing his lips as he scrolled down in concentration, looking for a reply, waiting for Tara to write, and waiting as days passed.

When her daughter was eight, they moved again as a family. From New Jersey, where they’d lived for the shortest time anywhere, to California. During all that clearing up, sorting out, disposing, and giving away, she found the books she had totally forgotten about. Another memory lost in all the years that passed too quickly.

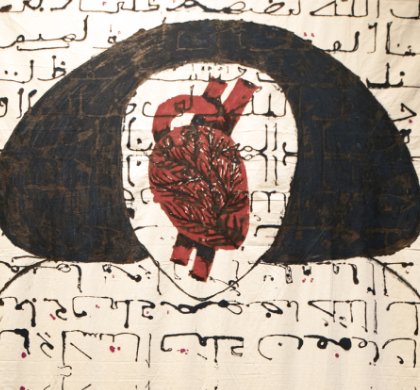

The classics she had read once, and many times over; even before Shishir sent along different editions of the same books as a gift. In cartons that he had shipped halfway across the world in a container ship, from Edmonton in Canada to Singapore, where they had moved after three years in Bombay. Hard-bound editions, with glittering titles on the cover, some with large print, and others with tightly packed in font, all printed on thin paper. The kind of books that bookshops offered for sale. As her father said, these were easy to buy, but very expensive to ship.

Now years later, as they prepared for yet another move, Tara pulled the books out, from the bottom row of the first bookshelf that had accompanied them house to house, city to city, across countries, through every phase of their married life, from newly married couple to a career wedded couple, to the time they had drifted apart in the years of childlessness, and the years she was a trailing expat wife. She knew she would pull the books out, in a similar gesture, even ten, fifteen, twenty years later, when they moved again, when their daughter had moved out to college, and they were no longer a family of three. Life had been one of movement and the books had stayed in that one constant place, the bottom of a bookshelf, and memories had given way to other memories, and some had been totally lost.

The books had never been inscribed. Shishir was not the kind to leave any endearment on the front pages. Nothing like, to my dear niece, or dear Tara. There was just his name on the carton. In Singapore, the books had been held up by the customs. In that country, where they had moved, three years after their marriage, they hadn’t known anyone, least of all someone with influence they could approach to help them get the books through customs. In the end, her husband had to fill in three forms, get them photocopied, scanned, and then emailed to three different officials before they went to Changi airport to collect the carton. At least most of this work was online, she told her husband. But he’d had to give up half a workday and then drive all the way to retrieve the carton.

‘Someone from Canada, eh?’ The jovial man at customs handed the carton over, his hands, and her husband’s meeting over the counter. He made them sign three forms all over again. She remembered Shishir then not for the books, but for the hassle he had put them through.

Now she pulled the books out, one by one, from the shelf, running her hands over them. The volumes of Henry James, Eudora Welty, John Dos Passos, fresh Library of America copies. She would pack them again to take them across the country: New Jersey to California. The truck would take four days, the moving agency had assured them. Weird man, she thought about Shishir, when arranging them yet again in the bookshelf in their new home.

In their new house in Los Angeles, one that overlooked Redondo Beach, she had more hours to herself. School hours were longer, and there were many afternoons, Tara found herself alone.

She returned then to a long-abandoned project: writing about her family. She had spent so many years apart, geographically, and even deliberately away, that it was difficult and easy at the same time. She felt she knew everyone in her family more vaguely now. They were cardboard characters who needed filling in with her imagination. There were those who had died, like Older Sister-in-Law who had lived all her life in Calcutta and succumbed to cancer. Three years! Tara would always remember Sister-in-Law’s raised hand, her three fingers moving like an angry god’s trident, a mini-sized one.

She thought also of Shishir, her uncle, in Edmonton with a sudden sad pang. At one time, she had exchanged so many emails and messages with him. But she couldn’t remember most of what he had told her. That afternoon, when she had an hour or so before she picked her daughter up from school, she did look for his last email. But again, other things came up, never that note, of which she had only a vague memory. What had he said? The usual things, or something different? Congratulations on your baby. Welcome to parenthood. Hope you bring her up well.

An hour or so later, when she went to pick her daughter up from school, she was still thinking of her uncle, and her elusive search. After buckling her daughter to her seat, as she settled into her driver’s seat, Tara asked her the usual questions about school. The questions she knew her other friends, all mothers, asked their children. Families thrived on such things – the routine, and the banal – and perhaps these became special over time. What had alarmed her once in her bohemian days in Bombay, was the frightening mundaneness of marriage. Two people growing old with nothing to say to each other, or to others, even about children. She still didn’t know what was worse: being childless and having nothing to talk about and having children and still having nothing to talk about. She had felt the world to be intolerable then. How had all that slipped away? Where had that panic gone?

The misery she had wallowed in had led her to her forget so much. She no longer remembered the things that had once found intolerable. When she couldn’t even bring herself to intrude into her husband’s forever busyness. The weeks she had thought of a sperm donor. And had even imagined affairs. Secret embarrassments like these that she had almost inflicted on herself.

‘Do you know you have a granduncle of sorts? In Canada?’ She asked her daughter, who was strapped in her car seat, her eyes level with the window bottom. Tara liked the way her daughter looked at the clouds, or a plane flashing past, her eyes always wide with wonder, her chin lifted, and her mouth half open. The same feeling she got, her daughter had once told Tara, when she was high up on a swing.

They said these years never lasted. Nothing did. Still she was glad those years of her deep unhappiness had gone. All she had wanted then was to write stories. Her own story though had already been decided by everyone she knew then. To be a mother. A happy, married, forever content, woman with child. A happy story with a bored woman at the end of it.

‘He is kind of strange, this granduncle of yours.’

‘How?’ her daughter asked.

‘Because no one could understand him. He just did things differently.’

Tara paused, before going on. ‘You know he once sent me a huge carton of books, and I never wrote back to thank him. Do you think it’s seven, or maybe eight, years too late?’

But her daughter’s gaze was held by the clouds, cottony white and feathery, scudding past, over the car window, over them too, slowly, and inevitably, quite like the passage of time.