Hussain’s Room

1

I sat in my car with the air-conditioner on till it was ten minutes to eleven. Then I stepped out into the heat and humidity. From the parking lot to the Humanities Building, I could take the shortcut across the lawn or walk along the road to the front of the building. Usually, I took the shortcut because there were a few tall trees that provided shade. Walking on the grass was a transgression but I thought of it as a privilege I was entitled to after all these years at the university. Today, however, conscious of the need to be blameless and correct in everything I did, I took the road, walking without hurry, knowing I would be on time, having previously calculated just how long it would take to reach Hussain’s room. I did not want to be early, even by a minute, because there was a chance of being involved in corridor conversation. But arriving late, even by a second, would be disrespectful. It would mean dishonouring my late colleague.

At the entrance the security guard got up from his stool and saluted me, ‘Jai Hind.’ The guards kept changing and most of them did not really know who I was. But they invariably greeted me with respect. I am bald, have a grey beard, and a lifetime of dealing with students has given me an air of authority. That the guards think I’m important is a bit amusing. Of course, I have my place. I teach and grade students. The reputation of the university depends on professors like me. But I know where real power lies. For some years I was a Dean and was invited to meetings where I saw the inner workings of a university. Now only rarely was I involved in the intricacies of administration. But there are times when the university relies on me to draw on my experience to smooth things over.

The task of overseeing the unlocking of Hussain’s room could have been given to a younger colleague. I wondered who had recommended my name as chairperson of the committee. Last year I had been given the responsibility of looking after the state education minister when he had come to attend the Convocation. It seemed like a minder’s job and my first reaction was to turn it down. But the Registrar told me that only I, Professor Sarma, could handle the minister who had of late become publicly critical of the university. The minister, who was also the local MLA, had played a crucial role in acquiring land, almost three hundred acres in fact, for the campus on the outskirts of Dulung town. In the early years, when the university campus was being built, he had helped us find suitable accommodation in Dulung. Recently I was part of a university delegation that had submitted a petition to him to help us acquire land for a new campus. As anticipated by the Registrar, the minister had asked pointed questions: why was the university lagging behind in rankings, why didn’t it have seats reserved for students from the region (meaning students from his community), and why hadn’t it as yet established a Department of Karbi? I knew my task was to avoid friction and so answered each question tactfully and calmly as though I was chairing a seminar on some contentious issue. Prior to joining the university, I had worked for some years in a college in Dulung and often ran into the minister in the marketplace, which he, an aspiring MLA then, was fond of frequenting. But my relationship with him had remained rather formal. Now, by the end of the day, he had thawed sufficiently enough to share with me details of the hunting incident in his youth which had cost him an arm and left him with a partially damaged eye (the reason he wore dark glasses most of the time).

The convenor of the committee was Dipankar, one of our assistant registrars. He had arrived early and was waiting outside Hussain’s room. I liked Dipankar. He was a sincere young man, anxious to do his job well. He looked relieved on seeing me, a senior professor on whose elderly shoulders the blame would fall if something went wrong. ‘The key isn’t in the office, sir,’ Dipankar said. ‘I have sent someone to the security desk.’

The committee members began to arrive. There was Professor Shipra Chakraborty who was the Head of the Department of History, and Dr Hanse from the Department of Assamese, the latter included, I suppose, to ensure neutrality. And there was the new security officer, burly and moustachioed, who had lately retired from Assam Police. Though he looked every inch a cop, he had an academic side which had led him to do a PhD in community policing. He seemed keen on being regarded as a scholarly person and was disappointed when he was not. Maybe that is why he was picking on Dipankar now. ‘You should be introducing me,’ he said, accusingly. Shipra and Dr Hanse assured him that they knew he was the new security officer but he continued to bug Dipankar: ‘Where is the video camera?’ he asked. ‘We need a video camera’. ‘Our mobiles will do,’ Dipankar replied, annoyed at this impromptu request. It wasn’t easy to get a video camera and an assistant at such short notice. ‘We always video such matters,’ said the security officer, stubbornly. A couple of weeks ago an unhappy student had hung himself in his hostel room. That particular committee had videotaped it all: the breaking down of the door, the body hanging from the ceiling fan, the sad room…. ‘We can use our mobiles,’ I said, ‘but there is no need, really.’ A video recording could unnecessarily complicate matters, especially if found its way to social media.

I hoped the conflict between Dipankar and the security officer wouldn’t escalate. Tomorrow was Saturday. I planned to write my chairperson’s report and submit it to the Registrar on the next working day. This would allow me to move on to other things. I certainly didn’t want any complications.

As we waited for the key, it was inevitable that the talk should turn to Hussain and how he had suddenly left us. Hussain had literally dropped dead. He had gone to Guwahati for a medical consultation and had collapsed while waiting for the doctor, in the doctor’s waiting room. I did not know that Hussain was seriously ill. There was a time when we were close. But a misunderstanding had crept in, and Hussain was too proud, too defiant, to make any move towards restoring our former friendship. He was essentially a loner and like most loners he had too high an opinion of himself. He did not consider me a historian. So, it was ironic that here I was given the task of saving him from becoming social history.

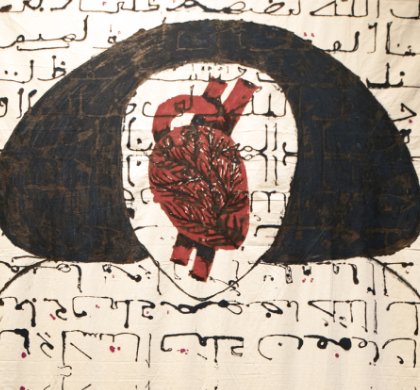

Soon after Hussain and I had joined the university we stumbled across a missionary report on a black boy, a former slave, who had been a student in the American Baptist Mission’s orphan school in Dulung. Both of us were keen to write the region’s unwritten histories or, where historical accounts existed, to write them anew. The report, which we found among the papers of the Eastern Theological College in Jorhat, fascinated us. We wanted to write a book on the African boy but there was too little. The report did not even mention his name. We gathered that he was sixteen years old and that to escape his master he had boarded a Dutch ship in Lisbon that was bound for Calcutta. When he arrived there, in the summer of 1848, he had gone in search of Christians. The Baptist missionaries who provided him shelter thought he needed saving from the temptations of the heathen city. They sent him to their remote mission station in Assam. The boy’s presence had caused a sensation in Dulung. People from the surrounding villages had flocked to the mission compound to see the ‘wild man’. They even counted his fingers and toes to see if he possessed the attributes of a man. What part of Africa did the boy come from? How long did he live in Dulung? (The Dulung Orphan School was closed down some years later.) How did he process his experiences? What were his thoughts and feelings? Only fiction could provide the answers and so I had written an article for the special Bihu issue of an Assamese magazine, trying to bring the boy to life by putting myself in his shoes. It was enjoyable but not easy as I had to craft scenes, write realistic dialogue, create convincing characters and a credible plot. The piece had proved quite popular but Hussain had not approved – I had taken liberties with the source material. It wasn’t worthy of a historian, he had said. I wasn’t hurt then or later. His history of church missions in Northeast India and his papers on the battles of Kohima and Imphal are all solidly researched but ultimately unhelpful. Sometimes you need a little poetry.

Dipankar now reported that the guard at the entrance did not have the key. He made a phone call to the Engineering Cell. We continued to wait in the corridor. It was hot and a breeze would have been welcome. A couple of colleagues walked by, refusing to make eye contact because they weren’t sure whether to greet us. A few students on their way to class stopped out of curiosity and were shooed away by Dr Hanse. Finally, a man from the Engineering Cell arrived and opened the door with a master key. We entered.

2

If Hussain had not died suddenly, none of this would have been necessary. When I am unwell my wife makes a fuss and takes me (against my will) to the doctor. But Hussain was a bachelor and had told no one about his illness. There was no reason to suspect he was unwell. He had looked fit for a man his age. In fact, time had been kind to him, at least outwardly. His elongated body, which had caused him embarrassment when young, had become more coordinated. His longish face was covered in a distinguished-looking beard which he had begun to grow when he had arrived at middle age. And there had been no noticeable slackening in his activities: teaching, reading, writing, and attending seminars.

‘Who is the girl who is always sitting in your friend’s room?’ my wife had asked me one day over a decade ago. I was annoyed, a habitual reaction on my part when she brought up gossip of this kind because, well, full disclosure: I had a past, one that was the source of some marital conflict.

I explained to her (suppressing my annoyance) that if you taught well, you became popular, and students sometimes sought you out to ask questions. Hussain taught with an intensity that was attractive. In a department like ours the students were mostly young women and sometimes temporary crushes developed. Also, back in those pre-#MeToo and pre-#LoveJihad days, it was okay to be a bit of a player. ‘What are my chances with _______?’ I had asked a colleague. It must have been reported to her for some days later dark eyes had met mine and I had the thrill of knowing I had an accomplice …

I blame Shipra for what happened. She has always been a bit of a busybody. ‘We respect him,’ she had said, sanctimoniously. ‘There is gossip. You better tell him.’ And so, I went to Hussain’s room. And there they were, Hussain and the girl called Dimpy, deep in conversation. I had never seen him so animated. ‘Give us a minute,’ I said and immediately regretted it. My words sounded like chalk scrapping a blackboard. ‘Yes, go outside, Dimpy,’ Hussain said, very reluctantly. Then I delivered my remarks, more or less as scripted by Shipra: ‘I don’t care how you will do it. But do it,’ meaning bring this to an end. Hussain did not reply but his face had darkened with anger.

Some days later I saw them at a restaurant. I was there with a few students, one of whom was _______. This was how you did it, you went in a group, so that it didn’t look like a date. But poor Hussain was not a player. It was probably the first time in his life that he had fallen in love and the experience had blindsided him. Naturally, there was talk.

University campuses, as any player will tell you, are like transit lounges. The only near-permanent denizens are the faculty and staff. What Hussain’s thoughts and feelings were in the years that followed I have no idea. He had become impassive and remote. But a couple of years ago they were sighted. In Guwahati, in a shopping mall. It was Shipra who brought the news. ‘Your friend hasn’t given up,’ she mocked me.

If the relationship had not ended, if it had continued, there was an urgency now to see what incriminating materials might be found, and what potential they had for scandal.

3

We entered. ‘We should be recording this,’ the security officer repeated. But nobody did. The first thing I saw: a light jacket that Hussain sometimes wore on winter days. Dipankar opened the windows. Light flooded the room. We could see trees and flower beds. It was a normal day on the campus. The gardeners were at work, removing fallen leaves. On the road there was an occasional car and a stream of student bicycles. I had a feeling of sadness at the ordinariness of death. One day I too would be gone. I made a mental note to get my room and possessions in order, so that there would be no need for anyone to rifle through my things. I am careless about my keys. I would ensure security had an extra key.

I looked around the room. How meagre Hussain’s belongings were! His computer (not his own but university property), his laptop which, for some reason, he had not taken on the trip with him, his jacket, a few bundles of answer scripts, stationery in the form of ball pens and a couple of unused or discarded notebooks, his tea kettle (he avoided the canteen), a tiffin carrier of the kind children take to school, a wall calendar with his markings, and his books.

Some bachelors tend to be tidy because they do not have wives or daughters to clean up their mess. But Hussain was not a man of tidy habits. And because the room was messy there was a feeling of normality now, as though he would walk in any minute.

The security officer said he had not the honour of meeting the deceased but had heard many good things about him. He didn’t look his age, he had heard. Shipra agreed. ‘He was such a nice man,’ she said. ‘He was so young. You wouldn’t guess he was in his sixties.’ ‘He greeted everyone nicely,’ said Dipankar. ‘Didn’t behave like a professor.’ Dipankar had a grievance against rude faculty. He particularly disliked the assistant professors who he thought did not respect the staff. ‘One of my neighbours suddenly died,’ Dr Hanse said. ‘He was watering his plants and the next moment he had a heart attack and was gone.’ I waited impatiently. I wanted to finish the job as soon as possible, quietly, without attracting attention, especially of the wrong kind.

Shipra took charge. She is of small stature and looks rather girlish. When she goes to the shops outside the university gates, she attracts the attention of the shopkeepers with the helpless looks and the vague answers she gives to their questions, but turns into an assertive customer once she finds what she is looking for. Now she wanted Hussain’s room. As Head she was always struggling for space. It was over a month since Hussain had died. There had been demands for the room not long after, cautiously expressed to Shipra. She had taken up the matter with the university.

She and Dipankar began to separate Hussain’s books into two lots: one personal, the other to be returned to the library at the earliest. Dipankar made a list of all the books. ‘So, he liked to read,’ remarked the security officer. Dipankar gave him a scornful look. ‘Some professors read more than this. You should have seen the books our last Vice-Chancellor had. I had to hire a truck to send his books to Guwahati when he retired.’ Hussain’s books included a couple of dictionaries, a large number of history books, and some works of sociology and anthropology.

There were a few files as well to be returned to various sections of the university administration. Next it was time to pack his personal belongings: the stationery, the laptop, the tea kettle and the jacket. These were to be returned to his next of kin. It wasn’t quite clear if they would come and pick them up. Apparently, there was a serious quarrel among the siblings over property and Hussain had lived a life apart. ‘We will pack his things and keep them in the store,’ said Dipankar. He had brought several large boxes.

Then came the tricky part. The drawers of Hussain’s desk were all opened. There wasn’t anything in the form of letters or photographs. Next came the computer. Dipankar tried to switch it on but there was a password. He used Hussain’s intercom to call the computer engineer. Dipankar’s voice took on a conspiratorial tone. The committee was exceeding its jurisdiction – there was nothing in the terms about looking into the contents of the computer. But it was university property and would be allotted to someone else. Who knew what secrets were lurking in its hard disk? The computer engineer said he was coming over.

While we waited, Dipankar talked about the few suicide cases he had handled. Young students killing themselves in their rooms. The phone calls to parents, the media interest.

The computer engineer came. He seemed aware of the delicacy of the situation and had come himself instead of sending an assistant. Logging into the computer took a long time. Finally, it was declared safe. There was nothing of interest there. Evidently Hussain had not used it for a long time, preferring his laptop. If there was anything incriminating, it would be in his laptop. But that was his personal property and we had done enough prying.

4

The heat was already getting intense even though it was only nine-thirty in the morning. I walked to the Humanities Building from my car, once again taking the road and not the shortcut across the lawn. It was Saturday, a holiday, and the campus had a deserted air. The Humanities Building loomed over me not as an imperturbable mass but as a sentient being, acutely conscious of its reputation and public image. I had a sudden vision of all the committees at work, each one doing the university’s bidding, men and women speeding and posting, so to speak, over land and ocean without rest.

I always wake up early but on Saturdays and Sundays I laze in bed. There is no pressure on holidays. Classes always give me a little anxiety even though I have been teaching for decades. Therefore, on working days usually I am up by six to look at my notes. It is only after my lectures are over that I find myself relaxing. Like so many of my colleagues who are saddled with teaching and administrative responsibilities, I find myself writing and doing research only on weekends.

In the back issues of the Baptist Missionary Magazine, I had come across references to Lucien and James, two lads who went to America in the mid-nineteenth century, and assumed that they were among the very first from our part of the world to travel abroad. Therefore, I was surprised to know that a rhino had travelled to Europe in 1741, where it had survived for seventeen years despite the very different climate. Clara, as the rhino was named, was displayed in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Venice, and London. I had done my research into the logistics of transporting a temperamental, three-ton female rhino in an age of horse driven vehicles and bad roads (coach suspension came later, in the nineteenth century). But the writing also required me to imagine myself as Douwemout Van der Meer, the Dutch sea captain who had rescued the rhino calf from hunters and had transported it from Assam to Europe. I was looking forward to spending a part of Saturday morning immersing myself in the strangeness and wonder of this story. But then Shipra called.

Like me, my wife had been looking forward to a relaxed Saturday. She served me breakfast, complaining a little about how the university gave me no rest at all. But she had shared my life long enough to know that a phone call on a Saturday was not something you ignored. Nor would such a call be made for no reason. She didn’t ask me what the emergency was.

The security guard had been alerted and was waiting for me, holding the key to Hussain’s room. I took it from him, ignoring his dangerously insolent grin. I didn’t ask him about the visitors but curtly demanded the museum key.

She looked different. Her once curly hair was straightened out in the new fashionable manner. She was a college teacher now, she said by way of introduction. What struck me more than her appearance was her poise, which is why the thought of asking her to leave did not even occur to me. Her husband was with her who, I later learnt, was making a name for himself as one of Guwahati’s best paediatricians, and a restless little boy. Something about her husband, his clean and open face perhaps, made me take to him. I opened Hussain’s door. It seemed intrusive on my part to accompany her. So, I suggested that she go in. Then I took her husband and son upstairs to the museum where the exhibits would perhaps keep the little boy occupied for a while.

I came back alone and waited in the corridor, resisting a strong urge to smoke. The university is a no smoke zone. If I want to smoke I usually go home (where I smoke in the bathroom). Sometimes I go to one of the small restaurants outside the university gates.

‘No hurry,’ I had said to her. But what would she see? Just a bare room. What was her visit about?

We said goodbye in the parking lot. They were driving back to Guwahati. It was a long journey they had undertaken. Should I have told her about the speeches that were made in Hussain’s condolence meeting and how highly regarded he was? But I didn’t.

The visit disoriented me. I went home and waited for the day to right itself. By evening it had. On Sunday morning I sat down at my desk. Usually on holidays I ignore emails but today I read and replied to a few. Then I spend a couple of hours setting a question paper. It was soothing to write it out in longhand: there are universities that still require you to submit handwritten copies. Next, I composed a recommendation letter for a former student, something I had been postponing till now. Finally, I began to write my report on Hussain’s room. I described briefly how the committee had visited the room and what it had discovered there. I mentioned the files we had found and asked they be sent back to the administration. I added Dipankar’s list of the library books Hussain had borrowed and requested the books be returned at the earliest. I noted that the computer was in working order and that it could be re-allotted. And, of course, I included the list of Hussain’s personal belongings and books which were to be sent to his next of kin. I would hand in the report first thing tomorrow. It was an easy report to write.