The Winning Move

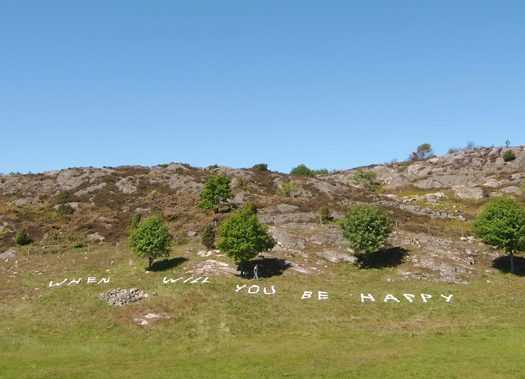

Untitled (W.W.Y.B.H.), 2010, Resin, steel, Dimensions Variable, approximate 200 feet, Installed in the ancient burial site of Pilane, Sweden

The Winning Move by Neeta Deshpande

The clock seems to be skipping minutes when I make it to the devghar, wondering how much time I have to put on my shoes. The cool stone floor invites me to sit. There is no puja today; no class test. Yet, Renuka devi must know why I’m here. I close my eyes before the Gods seated grandly on their perches. The glow of their room gives way to a pitch dark. For me, it’s only Renuka. Her red face with its big bell-like nose and boat-shaped eyes appears as if in a dream. But, only for a few moments. Then, memories …

And now, the most important post in school: the President of the Literary and Debating Society. Who will contest for elections from ninth standard? Ava teacher’s voice is loud and demanding. And my best friend Seema raises her hand just a little after me.

You must know, Renuka. You must know what today will bring. But I have no idea. And perhaps it’s better this way.

A girl from the eighth declares to her friends before the prayers one morning: ‘I think Seema Tupsande will win. I don’t know about you all … but she has my vote for sure.’

You know I need you, Renuka. More than ever. I promise I’ll do whatever I should. But stay with me, at least today.

I overhear Seema saying to Pooja and Mala a week before the elections: ‘If I’m President, I’ll make the Society really work. Now it’s just become a joke. Hai na?’

A soft hand on my shoulder, and then … the clock … my shoes … Mother! There she is, bending down and looking at me kindly. You don’t want to be late, she warns, as I touch her feet quickly. Then I put on my shoes in a rush, as I hear Father’s slippers flip-flopping loudly down the steps. Before he reaches the last step, I mount my cycle! Only fifteen minutes before the gates close, and we start singing ‘God lead me through the day’.

As I rush past the little garden at the school entrance, I hear Seema laughing with a junior. This can’t be how she feels, can it? She must be drowning in stress by now, like me. What pretence! But a moment later, I’m ashamed of doubting my best friend.

Besides, why would she be stressed? The girls are almost in love with her, always asking for her help with homework and activities. They have forgotten that I even exist. Or am I just nervous?

‘Seema Tupsande’. Kashmira teacher’s voice had tinkled with affection on that day I’d met my companion, as if she were the new girl’s aunt. But what kind of name was that? Seema was fine. But Tupsande? I’d stifled a laugh as I’d thought of its meaning. One who accidentally spills ghee! To my utter horror, Kashmira teacher seated the new girl right beside me, in place of my friend who’d left the school.

I shot my neighbour a glance then. Her skin was darker than any of the girls in class. Her braided hair was almost dripping oil. And what a long skirt! Why did she have to be seated next to me? Through the period, she sat wholly engrossed in every word Kashmira teacher uttered, as if she were Dimple Kapadia or something. What a big bore.

I look up to our classroom on the first floor and wave to Seema. Surrounded by girls from our class now, she’s smiling away, as if she’s confident that she’ll win. No, I won’t run up the stairs to talk to her. Instead, I walk back to the garden at the entrance to wait for Pooja and Mala.

Seema had been brave enough to approach Pooja, Mala and I during the short recess, on that first day when she joined our school. She ignored the unwelcoming look on my face, and started cautiously: ‘I wanted to ask you … The monitress told me to shorten my skirt to the knee. Are long skirts not allowed?’ My friends giggled, and whispered taunts. By now, our other friends had joined us. And then Pooja, who took it upon herself to represent the group, turned to Seema: ‘Do you really spill ghee all over, Miss Tupsande? Do you have too much ghee in your house? Must be, because you’ve applied some of it to your hair too.’

The giggles gave way to loud laughter, and Mala had to raise her voice in order to be heard: ‘And about the skirt … why don’t you come to school in a lehnga instead? Right to your ankle! You should wear a pink lehnga you know … with your dark skin!’ That sent Seema scurrying back into the classroom. As she cried silently to herself with her face in her hands, I felt a tinge of guilt. When I returned to my desk, I told her to get her skirt shortened to the knee. And having said that, I resolved to ignore her. Forever.

When Pooja and Mala arrive, they ask me: ‘Why so serious?’ ‘Nothing, yaar,’ is all I can say. We line up for the morning prayers. I count the hours left before we’ll enter the huge, beautiful meeting hall, where sunlight streams through big windows, and the air is always still and laden with expectation. Elections are scheduled for the fourth and fifth periods. How am I going to wait through the first three classes and the short recess?

Taking my seat next to Seema, I wonder whether she senses my stress. My friend talks of home and the approaching summer and yesterday’s Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi. ’Ok I’m Satish Shah now,’ she declares, and then, dabbing imaginary sweat from her face with a handkerchief: ‘Oh, what a relief!’ She sighs exaggeratedly, mimicking his line after his frantic runs to the toilet. Now I have to laugh. Seema laughs too, and for a moment, everything is back to normal. But not for long. I almost want to ask her how she can be so carefree today. And how I wish she wasn’t sitting next to me! She, however, hands me a large photo of Sunny Deol from the latest Stardust. When I turn it around, I see the girl in the Parachute hair oil ad staring back at me.

Parachute! That’s what we’d nicknamed Seema when she joined our school, after the coconut oil glistening in her hair. She’d eat her tiffin all alone in class, and we never bothered to ask her to join us. Later, she would revise the day’s lessons, while we went off to play. After the prayers, she would reach for her cycle silently, and disappear without an expression on her face. And then, there was that day when the silly little pink comb peeked out of her skirt pocket. I was so surprised. And smug. Now why would anyone carry a comb to school? I was glad I’d kept my distance from her after all. She and her stupid little comb!

The shrill bell goes off to announce the short recess. We share our tiffins with each other, as Seema, Pooja and Mala discuss their plans for the summer holidays. Pooja will be visiting her family’s holiday home in Matheran. She will ride horses and eat lots of sugary, sticky chikki. Mala will be attending a Personality Development Camp with all kinds of activities – swimming, craft, music lessons, even film making. She’s so looking forward to it, she says with glee. And Seema will be taking typing lessons in an institute near her house. She’s hoping she’ll make new friends, though the typewriters might give her a headache.

‘What about you?’ they ask me, and I absentmindedly mumble something about programming our home computer. Thankfully, the bell rings again, and we enter class. Seema’s in front of me, and her pink comb still peeks out of her pocket.

Her pink comb! That was the comb on which she had played the birthday song a few weeks after she joined our school. How bravely she sprang to her feet and announced to our class teacher: ‘I can play Happy Birthday for Mala. If you’ll allow me to…’ Soon in front of a stunned class, Seema placed her lips on the comb. And before we knew it, ‘Happy Birthday to You’ poured out! Bewildered, I wondered if the notes were coming from the comb itself. When the class clapped with delight, Seema smiled a dazzling Colgate smile at our class teacher, and returned to her place beside me. That must have been the turning point for her, making her confident that she could make this new world her own.

A few days later, I asked her how she’d played the tune. And to my utter surprise, she was so nice! She quietly tore a sheet of paper from her rough notebook, and pulling it taut behind the comb, blew a melody between its teeth. I didn’t know then that this new girl would soon be beating me in debates, sports and NCC. Nor did I know that our inseparable friendship had already taken root.

The fourth period arrives. Ava teacher informs us that it’s time for the elections. We’re asked to proceed to the meeting hall with our pens. Seema walks behind me, discussing the Biology homework with Pooja. We enter the meeting hall and sit with the audience on the wide, ascending steps. The hall fills up slowly as more girls stream in. Preeti and Rekha from the tenth are arranging the wooden chairs on the stage. Vijay sir is testing the mike with a deep ‘hello hello hello’. And some junior girls rush in and out, running last minute errands. The hall is so unlike that quiet summer morning when Seema taught me how to face life head on, right here on these steps.

I had told Seema everything that morning, that too, just before the final Hindi exam. I was walking home from school the previous afternoon. I’d left my cycle at the shop behind my house to get a puncture repaired. Just as I neared home, a scrawny man cycling past me did something so … so disgusting and dirty … it all came back as if it were happening all over again. But how could I tell her? I couldn’t get his face out of my mind. When I ran after his cycle, he bit his lower lip menacingly, and said: Chal phut. Phut. Later I went straight into the bathroom and bolted the door, crying quietly so Mother wouldn’t hear me. I fell asleep earlier than usual. But I woke up many times through the night, distinctly feeling the burden of his touch. Yes, he touched me. My breast. He squeezed my breast, Seema.

My friend was quiet for a few moments. Then she responded, quite matter-of-factly, with her own experience. She told me how a middle-aged man would follow her on his bicycle every evening. One day, she got down, and turned her bicycle around. Then she cycled right after her pursuer. The man pedalled for his life, scared out of his wits by a puny little girl!

Seema turns to me and flashes a huge smile, as if she’s read my mind. I smile back, half-heartedly. Why does she have to field herself against me in this election? Our friendship doesn’t need this intrusion. Whether it’s doing homework, watching movies on the VCR, or playing Rummy and Not-At-Home, Seema and I have done it all together. We’ve talked about everything: first crushes, aspirations for junior college, family secrets. But we’ve always met at my house. I’ve only visited Seema’s house once.

It was on Seema’s fourteenth birthday, almost a year ago. Our driver had difficulty manoeuvring the car through the narrow gallis of her neighbourhood. And when I entered Seema’s home, I was wondering what kind of cake she’d have. I so wished for a Black Forest, as I removed my sandals in the verandah.

Inside, the drawing room was as small as the bathroom adjoining my parents’ bedroom. I wondered how an entire family of eight fitted in it, to watch Chitrahaar on the tiny television that blared away. The curtains were made of old sarees. The green paint on the walls was peeling off. And the flower-vase had gaudy, artificial roses, with dew drops of plastic! I thought about the cake some more, as Uncle asked me about school, and I wished I didn’t have to answer. But what was going on? Aunty had already brought out the snacks. We were served samosas and home-made chiwda. And no birthday cake was ever cut!

Our principal takes the mike to announce the candidates for the elections. Two candidates are nominated as contestants for each post by the teachers, from the pool of girls who are interested in that post. As Seema and I are called, we take our seats on the stage. The long list is read, as the chits are being handed out. My mind is humming with prayers to Renuka devi again. I smile at the sea of blue skirts and white blouses, hoping that the girls won’t let me down. Please, please, please, Renuka. You must help me!

In a few minutes, the girls are writing out their choices for one of the positions. I watch single-mindedly, as the monitresses gather the chits in plastic bags, and take them to their class teachers. Chits are passed out again for each of the remaining posts, and collected within minutes. Everything seems to proceed smoothly. But during the President’s election, we hear an argument in the back of the hall.

Tehmina teacher is shouting at the monitress for class X-C, who in turn seems to be defending herself. We hear only snatches of the conversation from the stage. ‘Where are your eyes?’ Tehmina teacher is saying. ‘These girls are putting more than one chit in the bag!’ I feel like running to the last rows, because I can’t hear a word of what the monitress says. But I must stay put.

All the plastic bags with the votes are soon collected, and taken backstage for the count. The hum of conversations swells in the hall. Teachers and monitresses have given up on maintaining the peace. In this flurry of activity, the argument between the monitress of X-C and the class teacher seems to be forgotten. Tense minutes pass by, perhaps half an hour, or even more. Finally, our principal takes her place behind the mike again.

‘Are you ready for the results?’ she begins, as if she’s a rock star addressing her fans. Silence descends upon the hall. I shift in my seat. Madam reads out one name following another for each post, starting with the Prophetess, and moving up the list to the Secretary. Pooja has lost, Mala has won. But I only care about one post. My dream, goal, destination. Will I make it?

‘As you all know,’ Madam is now saying, ‘between the two students who stand for the President’s post, the one with the higher votes becomes President, while the other contestant is Vice President. But I’m sorry to inform you that this year, there’s been some fraud during voting.’

The audience chirps to each other. ‘Quiet, please’ whisper the monitresses. Madam continues.

‘I’ve been informed by my staff that some students have cheated during the President’s election. I can’t go into details. But some senior students were caught casting more than one vote.’

More talking. Whispering. Gossip. Questions. Suspicions.

‘Quiet, please!’

‘Ideally, we would have liked to organise a fresh election for the President’s post. But we don’t have time. We’ve investigated, and arrived at what we believe is the correct result.’

Here it comes, I think. Will I make it?

‘When we counted the votes the first time, Seema Tupsande had won by a small margin.’

More chatter is followed by warnings for silence. I’m almost on the verge of tears.

‘But after we found out about the fraud in voting, we removed those votes from the tally’ Madam continues. ‘And here are the final results.’

As she reads out the numbers, a smile of relief passes across my face. I have won! By only two votes!

Madam calls me to her side and pats my back. Congratulations, she says. You deserved to win! As I walk away, I hear her talking to Pervin teacher. Madam is glad the result has turned out the way it has, because I speak better English than Seema anyway.

My English better than Seema’s? Really? And why is Madam saying this now? Soon, I can’t ignore the questions which assail me. Why is Madam happy that I’ve won? Is there a connection, a thread, something I’ve missed entirely because of my desperation to win? And then, the pieces start falling in place.

First of all, even if some students have cast more than one vote, I can’t understand how the teachers have found out the exact number of excess votes. Voting was anonymous. Besides, the blank chits which were handed out were not marked in any manner. So how could they have counted the precise number of extra chits some girls had thrown into the bags? How then had they determined that I’d won? That too, by two votes?

When I rush to my group of friends gathered outside the hall, they are angry. ‘That Madam,’ says Pooja. ‘She always has a trick or two up her sleeve…’ ‘The teachers have all the time in the world for a fresh election,’ says Mala. Others are in agreement: how could they have done this to Seema? Only my best friend is unusually quiet, as if she needs her space more than anything else. Her silence seems to disturb the others even more; they don’t want to let this go by. But what can they do? It’s then that Pooja pushes her braids back, and turns to me.

‘Why don’t you resign, Miss President? It wasn’t a fair election, don’t you agree?’

She pronounces each word carefully, somewhat tauntingly.

‘And after all, the winning move wasn’t your own, was it?’

The others stop talking. For a moment, Seema turns as if to look at my expression, then looks away. I remain silent; unable to think, feel, speak. Soon, our friends leave one by one, and Seema and I are alone, avoiding looking at each other like an awkward couple after an unexpected, bitter fight. I’m thinking about Pooja’s questions, and my response, or the lack of it. I’m upset, first at the teachers, then at myself. I turn to Seema to say something, but she blurts out instead.

‘I’m going to tell my father. He’ll show these teachers that we’re no less than them.’

‘But why do you think you’re any less, Seema?’ I ask.

‘Don’t tell me you don’t think I’m lesser than you!’

‘Why would I?’ My voice is now louder.

‘Then why were you asking my father so many questions on my birthday?’

‘About what?’

‘About the photos of Babasaheb in our house. That’s what.’

Before I can think of an answer, the bell rings. We rush to take our positions for the prayers. That Saturday afternoon as the harsh sun beats down on us, for the first time since we’ve become friends, I feel a cold, uncomfortable distance from Seema. I feel an overwhelming urge to run away from her – far, far away, to begin a fresh, new life, in a place where I can’t recognise the faces, where I don’t know the roads, where I won’t, even by accident, run into my old friend. I’m shocked. I’ve never felt this way about her. I must do something. After the prayer ends, I signal to Seema to meet me on our bench.

The younger students walk out in a line, and soon, Seema and I are dragging our cycles smoothly across the stone corridors. Everyone else seems to be in their usual jolly mood – chattering, gossiping, laughing. But Seema and I have nothing to say. After saying bye to our friends, we park our cycles outside the iron gates, and return to our wooden bench in the corridor. By now, I’ve decided: I won’t resign. I’ve wanted the President’s post more than anything else ever. I’m not giving it up so easily. Not even for Seema.

We sit in silence for a few minutes. Then she takes it upon herself to dispel the tension.

‘You really shouldn’t take this to heart,’ she says.

I look at her sheepishly, but she remains quiet. I can tell she’s holding something back.

‘What is it?’ I turn to her, the air stretched taut between us.

‘It always lurks around somewhere, you know’. She raises her voice a little.

I wait. When she speaks again, she seems to be fighting back her tears.

‘Now I think I shouldn’t even have tried…’

‘Tried what, Seema?’

‘Nothing, man. Just speaking proper English … enrolling in this famous school … having birthday parties! Only to compete with girls like you!’

She speaks almost as if she’s never been my friend. But not for long.

‘Leave it, yaar,’ she continues, wiping her eyes. ‘It’s not your fault.’

And before I can say anything …

‘This won’t come between us.’

As she walks away, I know she’ll stick to her promise. She won’t let the events of the day affect our friendship. She’ll try her best to forget, forgive, and move on, as she often says. But can I?

In the days that follow, Seema lives by her words. How I wish she had scolded me, shouted at me, accused me of being party to her unfair defeat. How I wish she had refused to talk to me during the recesses, wounding me with long silences. How I wish she had claimed her revenge, slowly, bitterly, one day at a time.

She does nothing of the sort, telling me silly jokes and sharing stolen photos of heroes from Stardust instead. I try to be my usual self too. But I can’t. My discomfort gets in the way of every little thing we do together. My guilt weighs down on our conversations, making my responses to her curt, sometimes rude. My ambition has ruined our glowing friendship. And yet, I continue to bask in the glory of a false victory. But though I pretend nothing is wrong, I can’t ignore the dreams that come to me every night.

I dream I’m stuck inside a manhole surrounded by stray dogs and litter, and I can’t get out. I dream I’m flying with the wind high in the sky, and no matter how hard I try, I can’t land on ground. I dream that someone has painted my face grey and black, and the stinking paint just won’t come off. I wake up and almost run to the mirror, when I realise it’s another of my nightmares. That’s when I run to Renuka devi instead.

As I approach the devghar, an imaginary bell starts tolling, forcing my sleepy eyes to remain open. The gods have got down from their seats and wait at the door, staring at me angrily. Renuka is among them, as if she’s been waiting for me to come. As I walk towards her, I train myself to say the right things. I will apologise. I will ask for forgiveness. I will do what I need to more than anything else. But what on earth! Just when I come close to Renuka devi, she seems to be vanishing. Hear me out, my mind cries, but her face is getting blurred. And as she disappears, I sense something strange about her, something I can’t quite put my finger on. Then all of a sudden, I see it, an expression I’ve never seen before. On Renuka’s disappearing face, rests a mocking smile.