The Boundary Man

I never liked the child.

I knew as much way before I had to wash his blood off my shirt. He had a limp handshake and wouldn’t look me in the eyes when I said hello. It made me think badly of his parents, Ganesh and Vidya. My initial thought was: They’ve ruined the boy.

After the first meeting I wasn’t enthusiastic about taking them to the family farm. Friends of friends from Bangalore that we agreed to show around, they had decided to spend their annual holiday that summer in the Northeast, and Ganesh, having been back in India for nearly ten years, quickly adopted the older brother I-know-exactly-what-you-should-do persona when talking to me.

This is what he said: Write a blog, man. Start a website for tourists. Find gaps in the local market. Make crores of cash.

It was a struggle not to dislike him, but I tried to hold out. Vidya was less polite, but more likable. She quickly bonded with Maya over what they missed about the west. ‘If Bangalore had an IKEA,’ she said, ‘I’d feel less like moving back.’

‘I’ve got the 2010 catalogue upstairs,’ said Maya. ‘I leaf through it all the time.’

While I winced at the thought of an IKEA up the road – I once put together an ASPELUND Queen Sized Bed using nothing but the two inch screw driver included in the flatpack – Ganesh looked at the family photographs on the walls, then started to educate me on the history of Shillong.

He had arrived the day before.

I went silent, and shuddered internally at how many hours of my time would be wasted. When he mentioned things I had an intimate knowledge of, I acted as if I didn’t know what he was talking about. I didn’t give him tips, or suggest places to visit, and I declined the chance to lend him any books – not that he was looking for that. What he wanted was to offer those things to me. I left him with my father-in-law and went into the garden to check on the three boys. The youngest one was picking on the eldest with the middle child. That’s how I think of them, by age. There is no room in my contacts list for kids’ names.

Even though the young one looked like he might become a sociopath and the middle child had a delighted look on his face as they bullied the eldest, I was on their side; the kid emitted those sorts of vibes.

Ganesh gave Pa the slip and followed me down. He wanted to see the compound. Then he asked me what I’d been reading, and to give him a top ten list of my latest discoveries, like everything was supposed to be exciting.

‘Actually,’ I said, ‘I gave away or sold most of my library before we left Sydney.’

‘I can imagine,’ he said. ‘When we left New York it was a nightmare.’

The whole day was like that only: anything I said, he bettered. All throughout lunch I just nodded. The motherfucker could talk underwater with a mouth full of marbles. I didn’t have anything to add and thus observed silence – his mild derision for me balanced by the charm he directed towards Maya, who, being pregnant for the first time, encouraged him to show off his knowledge of the process.

‘I’m an expert on giving birth in India,’ he said. ‘Ask them what they offer in the way of pain management. Keep harassing them till you get an answer.’

‘Ganesh read all the literature in the first week,’ said Vidya. ‘In the end I had to tell him to shut up with the facts.’

‘The doctors also got tired of me,’ he added – like he might have become a gynaecologist, if he could’ve been bothered.

*

He lost that smugness at the first sight of the claret seeping out of his first born. As I said, I never liked the child and his distress didn’t cause me the slightest discomfort.

Ganesh was out cold on the grass, and his boy was screaming in front of me – the sight of his own blood really making him shriek. I had not wanted to go to the farm, not with them, and this only confirmed my original reservations.

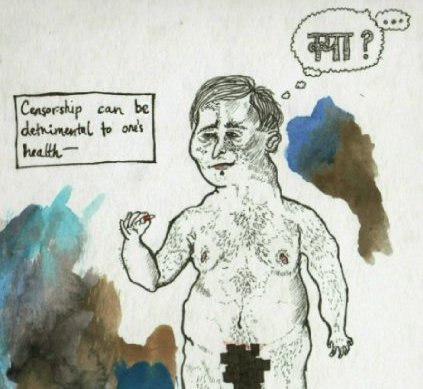

Even though it was the worst possible position for someone with a history of mental illness to be in, I maintained my self-control. I also understood that no matter what happened from there, the boy’s injuries, Ganesh being down for the count, and the way that I was now seeking out Vidya, could all be painted as a violent attack by a lunatic.

I’ve seen it before. A young couple goes for a weekend in the country with their friends. There is an accident: the boy – who has bipolar disorder – survives it unscathed, but the girl doesn’t come back. The police get involved, stories are written, current affairs programs compete for the best ratings and in every mention of the business some reference is made to the time when the youth had been sanctioned by his parents. His drug use is brought up – the friends are all interviewed formally – and the grieving parents of the girl do a bad job of holding back their hatred of the maniac who’d been drilling their daughter sideways for two and a half years.

But then a different thought occurred: I’m in India now, married into a well-connected, respectable family. I could kill them all and get away with it.

It made me smile as I strode back up the hill towards the cottage. Vidya was on the hammock and didn’t see me as I walked past. She had her sunglasses on and seemed to be enjoying her first moment of respite on the trip – her breasts flattening out on either side of her chest, a content smile on her face.

I didn’t say anything till I had to, not wanting to disturb such a peaceful sleep – something they’d never believe in an interrogation.

‘Vidya, Ganesh said he needs you down there. Your eldest one has had an accident.’

She was up in a second, slightly groggy, and asked what happened.

‘Just come down. It’s bleeding a fair bit.’

As a mother of three boys, she kept her cool. I suspect she thought that her eldest was overreacting, hamming up a superficial flesh wound.

She didn’t know about Ganesh yet.

*

I got back down the hill before Vidya, and couldn’t work out which of the wounded to go to first. The boy had taken off his shorts and was hobbling on one leg, pleading for help. Ganesh was still lying on the ground, but a few metres from where I first left them. He moaned loudly, and had both hands on his forehead. I tried not to let the disgust I felt show on my face, and turned to the kid. He was wearing a little boy’s underwear – white cotton with a blue border – and there was fresh blood dripping down from a bullet-sized hole underneath his right buttock, just on the curve where cheek meets leg.

The unselfconscious way that he displayed the gash relieved me of my hesitation to clean it, so I started pouring QUĀ – natural mineral water from the Himalayan foothills – over his exposed flank.

‘I’ll do it,’ said Vidya.

Good, I thought, as I stepped back to let her take over. Then I looked down at Ganesh.

Can you make it up to the cottage?

‘I’ll just take water first,’ he said. He sipped a bit, poured some on his shiny scalp and then fell back on the grass.

If he can’t walk, I thought, I’ll have to get Lambok to help me carry the fat bastard.

Ganesh might’ve read my mind at that point, because he sat up again and said he’d give it a go. His boy wouldn’t stop crying, and flatly refused to limp back up the hill.

‘I can’t,’ he said. I CAN’T – a slight American inflection betraying itself with the ANT.

‘I’ll carry him,’ I said.

It was hard to read Vidya’s expression because of the dark glasses, but she seemed annoyed with both husband and son.

‘It’s OK, my baby,’ said Ganesh. ‘I’ll carry you.’

The boy held up his arms and Ganesh lifted him – the way you might hoist a toddler – before they started up the slope.

Vidya walked beside them and I stayed a few paces behind, in case Ganesh stumbled back and needed a prop. When we reached the cottage they took the kid into the bedroom and put him on the bed. Ganesh went to sleep with him there on the single cot while Vidya washed the shorts. Maya and I cleaned up the dishes and packed the jeep, the other two little ones running riot as we did so.

We kept our itinerary and still went for tea afterwards. It was the last opportunity to save the afternoon. Even then, if Ganesh had suggested a beer and just relaxed – started talking to me like a normal person – I would have forgotten everything. Between the two of us and a few Carlsbergs I’m sure we could have found something to laugh about.

But he calmly ordered for his family – pointedly getting a coffee himself – and then looked towards us.

What are you guys having, Maya? I suppose PJ wants a beer.

I ordered a diet coke, and settled for a plain one when they didn’t have the former. Then I went down to the viewing platform to look at the lake. The two younger boys followed me and I told them to keep close.

Ganesh soon wandered across, camera in hand, and I tried to show him the water line for the monsoon.

‘Yeah, right,’ he said, as he turned in the opposite direction.

We didn’t speak the whole way back to Shillong.

Safely home, everyone shuffled out into the driveway to wish them goodbye. Handshakes, kisses on the cheek, the meekest thank you in the world from accident boy – who’d been ordered to do so by Vidya – and then they were in the jeep, their driver ready to take them back.

‘Thanks for today, Maya,’ said Ganesh. ‘PJ, you did well in the crisis back there.’

‘No worries,’ I said.

He was already looking away.

*

Pa wanted to know why I had let the kids cross the boundary line of our land.

‘Really,’ he said, ‘you should have asked permission from our neighbour first.’

When we’d finished lunch Maya suggested that I take Ganesh and the boys for a walk. I chose the path that goes directly down to the back fence. From there I planned to steer them left and circle around the property. You could do the whole thing in ten minutes, but with the kids I figured we’d drag it out for half an hour.

Ganesh carried the youngest, and the other two went to tell Vidya what we were doing, giving her a little push in the hammock as they did so.

I reached the end of the track and turned around, waiting for them. Ganesh was close behind, but his eldest two were still farting about.

‘What’s down there?’ Ganesh was pointing into the paddock of the next property.

‘It’s just an empty plot,’ I said.

‘Looks like a good place for the boys to have a run. Can we go down?’

The fence in front of us was broken, perhaps by a deer or stray cow. There was nothing stopping us from stepping over the wire and ambling down for a stroll – except for the fact that it wasn’t our land. But it didn’t seem like the sort of thing that demanded an official request. Hiking back up to Bah Phor’s to ask would have taken another fifteen minutes, and we were just going for a walk. But my father-in-law is a stickler for protocol and I thought, Pa would ask Bah Phor before he walked onto his property with visitors.

‘It’s not our land,’ I said, ‘but it should be ok. Just watch your step.’

On the path in front of us the fence had been beaten down but there was barbed wire strewn around, and a decent sized cement block that had been the foundation of a fence post. I put one leg on either side of the wire and stood ready to make sure that none of the boys tripped over it. Ganesh looked back and called out for the others to come.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘you take this one while I fetch those two.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yeah, just wander on and we’ll follow.’

He handed me the youngest and I nodded to the wire. ‘Make sure they don’t get caught in that.’

‘We’ll be fine,’ he said, winking at me. ‘You get used to this stuff when you have three boys.’ I almost replied, then thought better of it and walked away.

The kid landed face first, with the lower half of his body wrapped around the cement block. It had a rusty piece of steel rod sticking out of it, and a crown of barbed wire at its point. He’d bolted down the hill towards his dad, and then flown straight past him.

You could tell that there would be blood. We stood over him, Ganesh stammering about how fast it had happened, the kid still in shock and not yet aware of the hole in his shorts. Ganesh rolled him over gently and they both went pale, the boy starting to whimper before bursting into a loud cry.

I leaned forward to look at the wound and put my hand on Ganesh’s shoulder.

‘He’ll be alright,’ I said.

And then Ganesh fainted.

*