Blink

I thought I saw you just now, Nita, sitting on the divan, the way you liked to, legs tucked under you, hugging a cushion to your chest. I blinked, and you were gone.

Just like the day you were crossing the road, waving to me. I blinked – and I saw a truck where you’d been a moment ago.

I blink all the time, Nita, and hope you’ll appear when I open my eyes – as suddenly as you disappeared. They look at me strangely. They tell me not to keep blinking like that. Nobody understands. Not even Ma. Only one person would have understood – you.

I look at the divan again, Nita, and blink. But you don’t come back. The cushions and bolsters are strewn about, though, just the way you would’ve left them. Exactly the way you left your pillow on your bed every morning. Teetering over the edge. How I hated that, Nita, how I nagged you about making your bed, complaining to Ma, stamping my foot. You never cared, though. I couldn’t tolerate an unmade bed and so I’d grumble and push your pillow into its case, put it back in its place, and straighten your bedcovers.

But now I feel terrible about shouting at you. So I make your bed everyday. I mess it up again, and straighten it. Again and again. It makes me feel better. It makes me forget.

Ma comes in sometimes, and leans on the door, and watches me. She doesn’t say anything. Sometimes she just stares at some point beyond me. I look behind me then, to see what she’s looking at, hoping it’s you. I blink, and hope you appear. But you never do.

I go into the house now, straighten out the cushions on the divan, and go back to the rangoli I’m trying to draw on the porch. They didn’t let me draw the main rangoli in front of the door. Mami made that, with flower petals. They’ve let me draw one a little to the side. I don’t mind, Nita. Mine will be better than Mami’s.

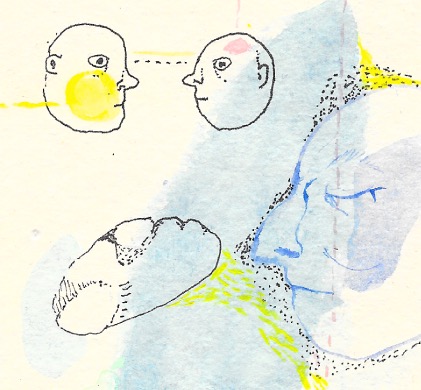

Do you know which rangoli I’m trying to draw? Not any old one, but the elaborate one you developed yourself – starting with a line of thirty dots and narrowing down to ten on either side. Remember? I watched open-mouthed as the piece of chalk in your hand flew in and out of the maze of dots. Whorls and loops appeared as if by magic, and just as I was sure it would become a tangled mess, you finished with a flourish, and there lay the most beautiful rangoli I’d ever seen.

You never noted the pattern down, Nita. Why would you? It was in your head, after all. I’m trying it out from memory, Nita, but I’m not getting anywhere.

We’re in Mama-Mami’s house, welcoming Raju’s bride home. The house is full of guests. Relatives. I don’t like most of them. They stare at me. But you would’ve enjoyed it, Nita. All this noise, this excitement. And I know you would’ve wanted to draw a special rangoli. But you’re not here, and so I’m going to draw it.

But they all look at me with pity. They think I can’t do this by myself. Perhaps they are right. But I’ll try.

Ma is here. ‘Did you take your pills?’ she asks, squats on her toes, and lays an arm on my shoulder.

She looks lovely, in an olive green Mysore silk sari, with jasmine in her hair. I look at her, and I feel like my heart has grown wings. The same feeling I got that day when you were crossing the road, smiling, the sun shining on your hair.

I try not to blink. My eyes burn, and I feel tears in them, but I don’t blink. Tell me, Nita, what if I blink, and Ma disappears too?

Ma sighs, and she gently closes my eyelids. ‘You haven’t,’ she says. She brings me the pills. I swallow them with water.

‘How’s it going?’ she asks, looking at the rangoli.

‘I’m trying,’ I say.

‘Good,’ she says, and smiles, but her eyes tell me she’s far away. She pats me again and kneads my shoulder.

‘What if I can’t finish it, Ma?’ I ask.

‘If you don’t, it doesn’t matter,’ she says. ‘But I know you will.’

She kisses me on the top of my head. Someone calls her, and she leaves.

Ma and I try not to speak of you, Nita, but both of us know who the other is thinking about. You would’ve been everywhere at once. You would’ve worn a ghaghra. A peach ghaghra with gold thread. That would’ve suited you. You would’ve run around, decorating the house.

Meena comes by. ‘The car will be here in two minutes,’ she says to me. ‘You’d better finish the rangoli quickly.’

I know what Meena is trying to say, abandon it. Or draw another.

‘Ok,’ I say, and she leaves.

I look around. Garlands of marigold, rajnigandha and jasmine hang at the door and in the porch. Little oil lamps have been lit and placed along the driveway. Everybody is clustering at the gate, and Mami is ready with the aarti to receive the bride.

I struggle with the rangoli for one more minute. Doesn’t this line form a loop around these three dots? And then turn sharply and pass under this dot, and then rise to meet – this loop? Or that loop? Or was it – perhaps – yes, yes, I think –

I hear the car approaching. I throw the piece of chalk down, and run to the gate. I look for Ma, and hold her pallu. She puts an arm around me.

Raju and his bride Latika get down from the white Innova that has red roses stuck all over it. Mami waves the aarti around Latika’s face. Its flame flickers in the breeze. She dabs kumkum on Latika’s forehead. Latika smiles. Raju looks happy. Our eyes meet, and his smile fades. I know he is thinking of you, Nita. His favourite cousin. He wishes you were here. I can see it in his eyes.

We walk back up the driveway, in a swish of silk. I go to the porch, and suddenly, I find it difficult to remain standing.

The rangoli is complete.

‘Hey,’ says Meena, linking her arm with mine. ‘You did it! It’s beautiful!’

Ma smiles. ‘I knew you could,’ she says.

See that? I told you. Nobody understands, Nita. They think I finished the rangoli.

But I know the truth.

I blink, and I blink and I blink blink blink. I know you’re here, somewhere. Come back, come back, Nita. Where are you?

I knew, Nita, I knew you wouldn’t be able to resist an unfinished rangoli.

But where are you?