My childhood friend Shankar Gowda used to come to school from a village that was about two kilometres away from my hometown. He was the youngest son of the Gowda, the head of the village, and the family had land, money and power. Shankar Gowda was tall, fair and well-built. He could have easily been the prince of any girl’s dream. But God wasn’t so kind to him.

His speech, voice, the way he walked, and his taste were all effeminate.

Shankar Gowda was the butt of many jokes at school. It was all too common for boys to speak to him, imitating his soft, delicate way of speaking, his girlish gait.

It was not just his classmates – even the teachers would make fun of him. I remember one Biology teacher, during a lesson, said that sometimes, due to chromosomal mismatch, a child is born neither girl nor boy. As he said this, his eyes wandered across to Shankar Gowda, and he broke into a nasty smile. The entire class shouted ‘Shankar Gowda’ and burst into laughter.

But Shankar Gowda wasn’t cowed by such remarks. Rather, he would join in the laughter. Indeed, his behaviour quite warranted their remarks. He would sing P Susheela’s Hoovu Cheluvella Tandenditu in a sweet, girlish voice. He would fill the end pages of his notebooks with new rangoli designs. When he spotted new saris hanging up in garment shops, he would exclaim, ‘How beautiful!’ He had no interest in manly games like kabaddi and volleyball; instead, he delighted in playing tennikoit with the girls. Wiggling his body, he would entertain us with his imitation of how prostitutes in his village solicited young men, calling, ‘Brother, come to me in the night, brother!’ This would send not only the boys but also the girls into fits of laughter. He would repeat this performance any number of times for our amusement.

Shankar Gowda always sat next to me in class. He wasn’t very good in studies and needed my help. He would copy my notes and in return he would get me gooseberries, wood apples, jamun fruit and sweet tamarind pods from his village. Sometimes he gave me the colourful rangoli designs that he drew. He was so sweet-natured, I had no qualms being friends with him.

But to his ostentatious family, his womanly behaviour was a bitter pill to swallow. His two brothers, his father, mother and everyone in his family implored him to change. How could he change something that was innate to him?

Once, he did not come to school for three days. Other boys from his village said he was ill. On the fourth day he returned, looking pale. After school, I asked him what had happened, and he took me behind the school building. There, where no one else could see, he removed his shirt and lowered his pants. There were deep welts and black bruises all over his body. I was horrified. Shankar told me that his father and brother had locked him in a room and whipped him to try and beat his girlish ways out of him. Afterwards they told everyone that Shankar Gowda was ill. They did not bother to take him to a doctor. Only his mother smeared coconut oil over his wounds.

Something shifted in Shankar after this incident; he was more subdued. The school annual day was drawing near, and our teacher had decided to make us enact the Draupadi Vastrapaharan. But which girl would be willing to perform the role of Draupadi disrobed in court? The boys suggested that Shankar Gowda be given the role – and the teacher agreed.

But Shankar baulked at the idea. ‘My father will scold me. I will not play a female character.’ The teacher tried to persuade him – in vain. Another boy was chosen for the part. On the annual day, Shankar Gowda walked into the green room, as the boys were dressing up for the play. He went over to the boy in Draupadi’s costume and caressed the soft silk sari, jacket and ornaments.

After completing my PUC, I went to another city to study engineering. I began to lose track of my childhood friends. I heard that Shankar Gowda failed in PUC once, appeared again, passed, and joined a local college to pursue his BA.

On my rare visits to my hometown, Shankar would invariably learn of my presence and try to meet me. But I tried to avoid him. He would continue to bring gooseberries, guavas and tamarind pods for me. As I no longer relished his attentions, I gave these things away to others. Once, just as I was leaving to return to college, he came to the bus stand and handed me a tiny gift pack. When the bus drove out of town, I opened the pack. Inside, I found expensive body lotion, powder, shampoo and aromatic oil bottles and a note saying, ‘I want my friend to look beautiful’. Worried that someone might see it, I hid the pack until the bus reached Gandi Narasimhaswamy hill. I threw it down into the valley, heaving a huge sigh of relief.

After I completed my engineering, I found myself a job in a reputed software company in Bangalore. Gradually my bitterness towards Shankar Gowda mellowed and I started to develop a soft corner for him again. He continued to look me up whenever I visited my hometown. It was heart-wrenching to watch him, unable to complete his BA and, damned by his family, drift into futility.

Once when he came to see me, I asked, ‘How is your father now?’

‘Now he can’t have it his way,’ Shankar replied with a guffaw. ‘He came to scold me, but I lashed him black and blue with a whip. He was in a hospital for fifteen days. Now that bole maga, that son of a shaved widow, never dares to cross my path.’ I suggested that he find himself a job. ‘Who will give me a job?’ he giggled.

He told me that he once went for an interview for a peon’s post in a local company. There were three men on the interview board. They asked him, ‘What are you good at?’ Shankar Gowda replied honestly, ‘I can sing and dance well.’

‘Well then, show us how good you are,’ they said.

He danced in front of them in the interview room, singing, ‘Ghil Ghil Ghil Ghilakku, Kalu Gejje Jhalakku…’ His show evoked peals of laughter from them.

‘Wonderful!’ they exclaimed and clapped as he finished. They promised him a job but he never heard from them again. After this, he lost interest in taking up a job.

Another time he took me to visit a Hanuman temple on the outskirts of the town. A mutual friend Kumarswamy, Kommi as we called him, ran a garment shop along the way.

I wanted to meet him. ‘Lo … Kommee…’ Shankar Gowda hollered from a distance. Kommi, busy showing garments to his customers, raised his hand to shoo him away contemptuously as one would do to a beggar. Unfazed, Shankar Gowda shouted again, ‘I know you are a big man, I am not asking you to talk to me. But look who has come!’ Catching sight of me, Kommi stopped his work.

‘When did you come, maaraya?’ he exclaimed. ‘Come, come inside.’ He took my hand, led me inside the shop and offered me a cool drink. Shankar Gowda simply followed us. Still holding my hand, Kommi chatted with me for fifteen minutes. But he never bothered to look at Shankar Gowda or ask him how he was doing. Just as we were leaving, Shankar Gowda asked, ‘By the way Kommanna, how’s Chandravva doing?’ That sent Kommi into a rage. ‘Son of a slut!’ He raised his hand, but Shankar Gowda dodged the slap, and dashed out of the shop, laughing hysterically.

I didn’t understand what was happening and asked Kommi. ‘Who is Chandravva?’

‘That suvvar blabbers nonsense, just leave it,’ Kommi growled. ‘Loose-tongued son of a whore.’ I joined Shankar Gowda at the corner of the street. ‘She is his keep – for the past two years,’ he explained. ‘She stays behind the Durgamma temple. He’s got her a gold necklace made,’ he added, naughtily.

There was no one in the temple when we reached there. It was cool and quiet. A bird sang in a crape jasmine that had formed a canopy over the temple. The scent filled the air. We prostrated before the idol, cupped our palms over the flame of an oil-lamp placed in a corner and raised them to our eyes. Shankar Gowda paused and applied a dab of kumkum on his forehead. He applied some kumkum on my forehead too, slowly dusting off the specks.

After we had sat in silence for a while, I said, ‘Gowda, you must get married.’ He laughed, so hard, that tears filled his eyes. Then, suddenly serious, he pleaded, ‘Please, you too don’t start making fun of me.’ I said sorry, and we walked home in silence.

That night, after dinner, I was sitting on the katte when Kommi came. ‘You are a Bengaluru man,’ he said. ‘You don’t understand what goes on here. Just listen to me. I’m telling you this for your own good.’ He told me that I should stop roaming around with Shankar Gowda.

‘Why do you say so maaraya? After all he was our classmate.’

‘Don’t ask me questions the way you used to ask teacher in the class,’ Kommi fumed. ‘Just try to understand. You are an intelligent boy. There was no one in our town to score marks like you, and there will be no one in the future either. You are the pride of our town. You have a good job in Bengaluru. I’m telling you this not just as a friend, but as an elder brother. Just do as I am telling you, don’t say a word more. If people in the town speak ill of you, I can’t stand it. Stop being associated with that son of a bitch.’

Five years passed. My parents moved to Bengaluru to stay with me, and I next visited the town on the occasion of a distant relative’s wedding. I must meet Shankar Gowda this time, I thought.

But shocking news awaited me. At the marriage hall, a few people told me that Shankar Gowda had committed suicide by hanging himself.

What made Shankar Gowda, who had the guts to lash his own father with a whip, hang himself?

None of those present at the wedding hall could give me a convincing answer.

That evening, I headed to his village. It was dark by the time I reached his house. His mother was sitting in the middle yard, sorting and picking menthya soppu. His father was reclining on a cot, smoking a beedi.

‘Who is it?’ His mother squinted, to catch a better glimpse of me in the dark. ‘Whom do you want to see?’ His father sat up. I introduced myself. ‘I studied with Shankar Gowda. I live in Bengaluru. I came to the town for a wedding and heard that he passed away.’ His mother wiped her eyes with the hem of a sari. ‘Please pardon me,’ I continued. ‘My intention is not to hurt you. The news of his death pains me. I just want to know why Shankar Gowda suddenly ended his life.’ His mother began to weep. She got up and went inside. I looked at his father, still smoking his beedi.

He took a deep puff, blew the smoke out and crushed out the butt on the floor. ‘How can we say why the dead are indeed dead? He’s dead, that’s it. May be he was fed up of life, so he went. May be he wanted to make us – who are left behind – suffer, so he went,’ he added, acidly.

‘No, no, I am sure not … but you would have to know the reasons behind his death…’

‘We don’t know anything, we don’t know,’ he raised his voice. Shankar Gowda’s brothers and their wives came out. ‘And after all, how does it matter to you?’ he continued, shrilly. ‘Who are you, his husband or paramour? We have had a bellyful of our woes and you come in here like a bear. Well, if you still want to know why he died, you too go hang yourself, and then you can catch up with him, up there and find out. Go, get lost,’ he pointed to the gate, his hands quivering with rage.

Without a word, I left. After walking a few minutes, I turned around. Shankar’s mother was standing at the backyard of the house and looking at me. She may tell me something, I thought, and started walking towards her. But she turned away at once, and went inside. I waited for a long time, hoping she would change her mind. But she did not come back out.

On the way home, I visited Kommi at his home. He had married and had a two-year-old son. He introduced his wife to me, a BCom graduate from Hagaribommanahalli village. Kommi sang praises of his son’s mischievous pranks.

After some time, I asked, ‘Why did Shankar Gowda commit suicide?’ Kommi did not reply. He turned to his son. ‘Sweetie,’ he pushed his son towards the kitchen, ‘go to your mother.’ Kommi turned back to me. ‘When will you go back to Bengaluru?’

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Then why do you want to dig into all this? Just go peacefully.’ But I couldn’t let it go. I sat there, quietly, looking at Kommi. Finally, he had enough. ‘Well, come let’s go out.’ He took me to an eatery on the outskirts. ‘I don’t drink,’ I said.

‘I know, but I must. Otherwise things like this cannot be said,’ he snapped. He ordered a drink and a snack. Then he began, ‘Brother, this town is no longer what it used to be. But you are the same, like you used to be as a small boy. Not changed. You are a good human being. Unlike us, you did not learn any vices. But the town is not like you.’ He went on in this fashion for a while, spouting amateur philosophy. Eventually I ran out of patience. I grabbed his glass and pulled it towards me.

‘Tell me. How did he die?’

Kommi was slightly drunk already. He looked up, straight into my eyes and said, ‘He did not die. They killed him.’

‘Who?’

‘His father and brothers. They killed him and then hanged him.’ He snatched his glass back and downed what was left in one swig.

‘He was the son of the house, born and raised there.’ I was on the verge of tears. ‘How could they kill him?’ Kommi poured himself another drink. He took a few sips before replying. ‘You know a bed bug, right? It slips into the mattress and bites you all through the night, disturbing your sleep. That son of a bitch was like a bed bug. Just because a bed bug is born and grown up in the same house, will people shower love on it? No. If they spot it, they will squish it and wash their hands clean. This is exactly what his father and brothers did to him. One day, when he was fast asleep, they smothered him with a pillow. Then they used his blanket to hang his body from the roof, and created a big scene next day morning, beating their breasts.’

‘Who told you all this?’

‘The entire town knows it, not just me. Those three men struggled to keep it under wraps. But how could Shankar’s mother conceal her grief? She told some people and cried her heart out. Those who heard her story consoled her, and in turn told others.’

I sighed. ‘He always minded his own business. What made them kill him? What a heinous crime!’

‘Not so fast, not so fast. I haven’t finished yet. If he’d minded his own business, nobody would have done this to him.’

‘What was his sin that he deserved death?’

‘He ran away to Mumbai. Stayed there for six months. He got his dick chopped off and came back wearing a sari and a blouse.’

I was dumbstruck. Kommi continued.

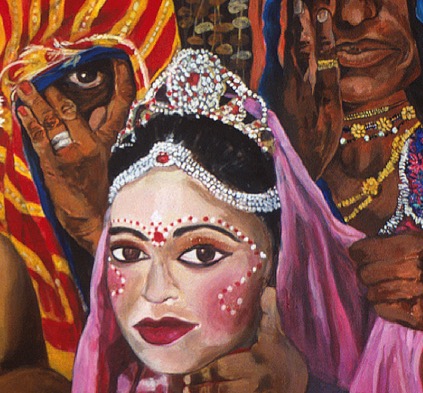

‘It was Ugadi, the chariot festival day. The shepherd boys were beating drums. The Nandi Kolu performer was dancing. This guy storms in, dancing away to the drummers’ beat. He looked like a film heroine. Where did this lady come to our town from, we all wondered. Youths began shaking and gyrating with her with the same vigour. Nobody realised it was Shankar. When the chariot drove into the yard of Basavanna temple, I and my wife bowed to the God in worship, Shankar came near us. ‘Kommanna, how’s Chandravva?’ he cackled and went away. I realised then who it was. I was newly married. All hell broke loose as my wife stiffened and began to nag me about who Chandravva was. I had a hard time pacifying her.’

‘From the next day onwards he began his antics. He came straight to my shop. ‘I want five bras and five panties,’ he said, coquettishly. I told him to get out. But he had become bold and brazen. ‘I will buy whatever I want. What’s your problem?’ he retorted, and left only after purchasing all the stuff he wanted. The news began to spread. People hounded his father and brothers with all sorts of questions.’ Kommi paused, before going on. ‘Tell me, what do you expect them to do when their boy turns into a woman, wrapping himself up in a sari? They tried throwing him out of the house. ‘I too have a share in the property in this house,’ he would assert, sticking to his guns ‘Share in the property is only for the sons, not for daughters,’ his brothers replied. I don’t know who in Mumbai had helped him get his courage up, he simply refused to leave the house. He ate there, bathed there and slept there.’

‘But his antics did not stop at that. He began luring the men in the town into his trap, one by one. His looks were exactly like a woman. He was stunning, believe me, women in our town are no match for him. His waist, his thighs, buttocks and breasts – he had got them all done. Men started going to him one by one. He ran it like a business. Women at home began showering curses on him. The Gowda and his family members hanged their heads in shame, unable to face the villagers. Not just that, the senior Gowda, who had never tasted defeat in a panchayat election before, lost that year.’

‘For how long could they put up with such indignity? Their family had lived respectably in the village. They grew weary and lost their patience.’ Kommi was drunk to the point he would disclose anything. ‘Finally his father and brothers bumped him off. Now everyone is at peace in the village.’

‘Instead of killing him, they could have given him his share in the property,’ I countered. ‘Even if they’d given him some money, he could have bought himself a house and lived there peacefully.’

‘Arre Arre Arre … here you go wrong again. He had no dearth of money. He had a roaring business. When he died, I heard that he had one-and-a-half-lakh rupees in his account. He had made his mother the nominee. Will anybody let go of money? Both the sons took their mother to the bank and withdrew the entire amount. Money wasn’t the actual problem. The problem was his pig-headedness – he insisted on staying in the house, claiming his rights. Tell me, what kind of madness was that?’ Kommi roared with laughter.

I felt my stomach churning.

‘See brother, this isn’t something you should feel sad about. He was sleeping around with just any man. I’m sure, one day or the other, he would have caught AIDS. He would have suffered and died but not before spreading the disease to the entire town. In fact, his father and brothers only did a favour by killing him before that happened.’ I didn’t want to hear any more. I paid the bill and hauled Kommi out of the eatery.

Still drunk, Kommi raved about Shankar Gowda’s acquired womanhood. ‘Whatever you say, that whore was such a spotless beauty, the kind one should only touch with clean hands. The way she wore a sari! The way she wore a matching blouse, the chain around her neck, bangles on her wrists, perfume, powder! Wow!’ We reached his house. ‘Good night,’ he said, shaking my hand.

‘Kommi,’ I said. ‘I want to ask you something. Will you tell me the truth?’

‘Ask my Lord, ask whatever you want. I will tell the truth, and nothing but the truth,’ he said, as if testifying in court, and began laughing at his own joke.

‘Did you too enjoy Shankar Gowda?’

Kommi’s laughter came to an abrupt halt. He dropped my hand. He walked to his door, then turned back. ‘If someone sleeps next to me, touching, pawing and canoodling, how I am supposed to control myself? I am a man, I have a dick. What applies to other men in the town – it is only fair that it applies to me as well.’ He strode briskly into the house and slammed the door shut.

This story will be part of a collection Mohanaswamy to be published by HarperCollins India at the end of 2015.

Translator Rashmi Terdal is a Bengaluru-based journalist working with a national English daily. She holds post-graduate degrees in Economics and Journalism. Besides socio-economic issues, she has an interest in Kannada poetry and fiction. Her poems have been published by leading Kannada dailies and magazines and by the Kannada Sahitya Academy.