The Itinerary of Grief

India was not a conscious choice. It wasn’t even an inspired one. It was a regression to my childhood when, growing up in Enugu, my parents ran a simulacrum of a democratic government in our family of five. Every school break, the children took turns choosing what we did during the holidays. And like every true democracy, those choices were neither unlimited nor especially attractive. They were already circumscribed by the four or so pedagogically responsible options our parents wrote out on a huge cardboard sheet, each one as boring as the next. I never took much pleasure in choosing how to spend my days out of school since none of the options included anything I particularly wanted to do like staying in bed and sleeping through the day, or going somewhere actually fun (the amusement parks my friends got to hang out at or window shopping at the mall.) To demonstrate my displeasure and disinterest to my parents, I would always just shut my eyes and stab a finger at the paper. Wherever it landed – the museum of Natural Science, Centre of Memories, some highfalutin art exhibition, was where we would end up being dragged to by our parents. India, like my childhood excursion destinations, was chosen, eyes closed, by a pin struck into the world map which lay unfolded on my desk. I would have preferred somewhere closer to home. Ghana. Senegal. Countries I had yet to visit but which already seemed familiar by the fact of being in West Africa, where I was sure to find jollof rice and some variation of fufu and soup. But integrity and all that. I had promised myself that I would let fate, the universe, whatever you want to call it guide me to a destination. What would be the point if I cheated? Where was the courage in that? Ejike always said that true courage lay in facing your fears head on. Thing was, I wasn’t sure which of my fears this trip was supposed to represent. I only knew I had to get away. Far away from home.

When Ejike and I bought this house – our first together – we had called it our forever home. We had waited for years, saving meticulously, to be able to get exactly what we wanted. A house in one of the quieter areas of Lagos, a gated community with its own communal generator and water supply. Three large rooms, a master with a walk in closet, a study and an open plan kitchen which segued seamlessly into the parlour. High windows to let in as much natural light as possible. A small flower garden at the back. A porch in front of the garden where we breakfasted on Saturday mornings and spent hours working together on complicated puzzles. No matter how long it took, how many Saturdays of piecing together little tiles which looked frustratingly the same, we always finished the puzzles. And we celebrated the achievement by popping a bottle, splashing out on an expensive dinner or dancing like deranged children around the house. I used to tease Ejike that our hobby held us together. As long as there was a puzzle waiting to be done, he could never leave me.

Once I had booked my flight to Delhi, anxiety like a raging fire, fanned out and engulfed my entire body. The last time I went on holiday by myself, I was still in college. Holidays then consisted mostly of backpacking. I had not needed more than a toothbrush, a few pairs of jeans and a camera. Once I met Ejike and moved in with him within months, we always holidayed together. Vacations carefully planned ahead of time, destinations researched and suitcases strategically packed so that we did not run out of underwear while away but also had room to bring back the souvenirs and presents I always insisted on buying. Twenty five years of always having him beside me on planes and trains, it felt strange to be sitting beside a stranger: a man who had his earphones stuck to his ears the entire three and a half hour flight from Doha to Delhi. Not that I minded. The woman beside me on the first leg of the flight had asked too many questions. What’s your final destination? Ah, India?! Bollywood!! How long are you going for? Your first time? Business or pleasure? I was relieved when she fell asleep after dinner and did not stir until we were close to landing. The company of strangers is heavily overrated.

Smog covered the early Delhi morning and for a minute I wondered if I could breathe. And yet it felt like since Ejike’s death, I had been holding my breath and this was my chance to breathe properly. The panic I had managed to swallow began to rise again, growing tentacles and clutching at my insides. What if there was no one to meet me? Paresh, the man who owned the guest house I had booked had been in touch the week before I left via WhatsApp with detailed instructions. For 1,500 rupees, there would be an air-conditioned car waiting for me. The driver would be outside exit 4 with a placard bearing my name. I could not miss him. But here I was, my duffel bag weighing heavier than it had when I left, searching the throng of people lining the curb outside the exit but there was no one with the promised placard. I shut my eyes and tried to still the rising panic. Breathe in. Breathe out. Inhale. Exhale. I opened my eyes and there it was. The Placard! How could I have missed it? I shook the bearded driver’s hand, allowed him take my bag and to lead me to his car. He seemed to have read my mood because he did the hour drive to Nizammudin East in silence, asking only occasionally if I minded the AC.

*

Ejike hated the cold. He had been dead fifteen minutes by the time I arrived but he did not look dead, his body was still warm to the touch. I imagined that the doctors had made a mistake, that Ejike would get up, kiss me and apologise for scaring me. I lay in the hospital bed beside him, refusing to let him to be moved. Ejike always said a man could withstand anything but cold weather. I could not imagine him in the mortuary, cold and alone and naked. One of the reasons why I had him buried – uncharacteristically quickly by Nigerian standards – within two weeks of his death was because I could not bear to have him locked up in some fridge waiting until the perfect funeral had been planned. Could a thing as heartbreaking as a funeral, ever be perfect? I took the earliest date the priest could give me, had funeral cards printed and to his brothers’ displeasure, had ‘our brother buried like a pauper. What is the haste?’ There had been no time to organise the sort of fanfare they had hoped to for their youngest brother. If not out of love for their own brother, they would not have come to the funeral, they swore. ‘I’ll never know what he saw in you. You couldn’t even give him a child. Not one.’ A parting shot from the eldest brother, meant to hurt and shame an already grieving widow who had hurt him. His words slid off my back, powerless and useless.

I shivered in the back seat and asked the driver to switch off the AC. I stuck my face to the window and looked out into the city. Perhaps all big cities tend to look alike in the dark. I could have been driving down any old Lagos street, trying to escape my grief. No one tells you this about grief: there’s no escaping it. It follows you around and hounds you. It comes in waves and catches you out at the times when you are not expecting it to. At the back of that cab, I hoped that the driver could not hear me sobbing.

The two of us had planned on getting old, really old together. But Ejike, fifty two and healthy had reneged on that deal. He had slumped at the gym and died in the hospital before I arrived, still clutching the remote control with which I had just switched on the tv for the nine pm news. There was no one to tell I was leaving the house. Ejike and I never had children. We also never wanted any. I always mentioned this because people assumed that we did. When we were younger and new acquaintances discovered we did not have children, most of them looked at us with pity, told us we would have children in good time, shared anecdotes of cousins and friends and sisters who did not have children for the first five, six, seven years of marriage and then suddenly when hope was almost despaired of, those same cousins or friends or sisters had twins or triplets or whatever number of children at once to make up for all the years of hopelessness. As if the world worked like that: taking with one hand and rewarding you bountifully with the other after you have withstood the test. We were for the longest time, in our social circle, before their children got older and flew the nest, the odd couple out. Throughout my thirties and forties, I kept being warned by well-meaning friends, who knew that our childlessness was a conscious choice, of the unforgiving biological clock and how mine was standing on its last legs. ‘Who’ll look after you in old age?’ they’d ask and I’d answer that Ejike would. We would look after each other. That was the deal. Now, at 53, I was not only childless, I had also become widowed. I did not care much for the former but the latter was a label which oppressed me. It was not a choice I had made. It was not a journey I wished to embark on. We still had an uncompleted puzzle waiting on the porch.

*

Paresh, the guest house owner was waiting up for me to arrive. His keys jangled as he opened the gate and with a huge smile, too wide for that time of day, welcomed me to Delhi’s Best. He showed me to my room, still jangling, jangling, jangling the keys in his hand, the way Ejike used to. I bit my tongue to stop from asking him to quit. It seemed like a violation of something sacred: this man in a foreign country, jangling his keys like Ejike did. When we had just got together, I thought the habit was borne out of the nervousness of seeing someone new, and even though it irritated me, I was too polite, too kind, too in love to say anything. By the time we had settled into the easy familiarity of an established couple, I no longer minded it. In fact, if he went away for a few days, I looked forward to the familiar tinkling of keys knocking against each other that announced he was home. Months after his death, I still kept his set of keys to the house and the car that we shared because I expected that he would walk in one day, pick them up and right my upended world.

From the day of Ejike’s death to almost two weeks after his funeral, friends and family (and colleagues even) had gathered around me. I was not permitted to be alone, as if they feared that if I was left by myself, I would break like an egg and there would be no scooping me up. They suffocated me with their ever presentness. I could not turn in my own house without bumping into someone, I said unkindly to my sister who, two weeks after Ejike’s funeral, was still staying in my house. Go home to your own family, your husband, your children! I had managed to get rid of everyone else, refused to open doors to guests and let the telephone ring out but this sister was obstinate. She stuck around, cooking me food I did not want to eat, fetching me newspapers I had no interest in reading. ‘I want to be alone in my house! You think I could have that?’ I hurled at her. And yet, now that everyone had retreated and Ejike had been dead three months, and silence, like a gossamer veil settled over the house, I could not bear to be in the house. But I also could not bear to let anyone in. I walked around the house feeling not like myself. Like I was someone who did not really exist. I walked through the rooms barefoot so that the cold tiles underneath my feet would shock me into feeling real. I stuck pins into the fleshy part of my palms for the same reason. For as long as the pain lasted, I did not feel that all I was, was a weightless, floating ball of sadness. I locked myself in the house and some days, blasted the radio at full volume to fill the house with sound, barely listening to whatever programme was on. I warmed frozen food and ate it straight off the kitchen counter. Outside, on the porch, the unfinished puzzle remained like an abandoned child. I did not know how this would end but I knew that I could not face the world. My school had given me an open-ended leave of absence (‘Take all the time you want, Dr. Abena. Your job will be here for you whenever you feel you are ready to return.’ The school’s director had personally come to the house to tell me, her tone appropriately understanding. They would find someone else to cover my classes, lead my sixth formers to math glory in the state exams, I was not to worry). In the bathroom, Ejike’s bottles of perfume and deodorant still occupied his own half of the cabinet, obediently waiting for an owner who would never return. I could not throw them away, just like I could not get rid of anything he had touched or owned – from his toothbrush to the sweat-stained t-shirt he had been wearing when he collapsed at the gym – but facing them everyday was also like a climbing a mountain I could never conquer, having rocks rain down on me and erase whatever little progress I made. I could not leave but I could not stay. Yet, somewhere between the microwaved meals and the radio programmes I was not even aware I was listening to, the story of a widower who took a job in another city to escape bumping into unhappy memories every waking day settled into my consciousness and that proverbial little voice asked me, Why not? Why not get away for a while?

*

That first night in Delhi, I dreamt of Ejike. He was in an unfamiliar park somewhere cold. He kept asking me to grab him a sweater, ‘Or a coat! Anything, babe. Please, hurry!’ Trying to reach him was like trudging through quicksand. He kept shouting until his voice was swallowed up whole by the wail of a siren. I woke up, goose pimples crawling up my skin and tears streaming down my face. The siren was still wailing and for a moment, I wondered where I was. The siren morphed into the ringing sound of the phone plugged in beside my bed. I vaguely remembered Paresh showing me the dining room when I arrived, rattling off meal times and asking if I wanted a wake up call at 11. I had said yes, imagining that I would have the appetite to eat but now all I wanted to do was stay in bed and cry. I could not do this. I was not brave enough. I would, if I ever got out of bed, buy a return ticket to Nigeria.

Paresh would tell me later, when I had been in India almost two weeks, that Indians were known for their intuitiveness. When I told him I didn’t want breakfast, he had heard something in my voice, something that told him it was not just the exhaustion of a jetlagged traveler. He had seen it in my face too when I arrived. ‘You wore your sadness like a second skin.’ But it was also more than intuition, he confessed much later, perhaps in my third week when he dropped me off at Humayun’s tomb and acted as my tourist guide (‘All part of the job description,’ he said when I offered to pay him for his time). He had trained as a psychologist and was specialising in grief counselling at the University of Iowa when his parents both died in a car accident. He had quit school and returned to India with no idea of what direction his life would take. It had taken several detours, some self-destructive, but eventually it had ended its meandering and ended here: turning the family home he had inherited into DelhisBest. He also ran an all inclusive travel agency which offered transportation to and guided tours of heritage sites in Delhi, Agra and Jaipur. Fifteen years down the line and he had never regretted it. ‘You must see the Taj,’ Paresh said. You cannot come to India and not see the Taj Mahal. Greatest testament to one man’s love for a woman! That sort of love! One in a million!’

‘And yet he had married two wives before her and three more after her? The great love of his life?’ I had not meant to sound as bitter and as sarcastic as I did but I could not control it.

Ejike and I used to tell each other that we could never love anyone better, more than we loved each other. We were lucky to have each other, we said . To have met each other, to have fallen so effortlessly in love and to have remained so for twenty-odd years was not something we took for granted. We knew our story was not typical. We had friends who got married at about the same time as we did who were separated, one – ever the optimist – was on her fourth husband. ‘I am looking for what you and Ejike have, Oby,’ she told me once. ‘And until I find it, I’ll keep searching.’ I could not imagine even looking for someone to replace Ejike. Our kind of love was one in a million, not this Shah what’s his name’s. Every day, I was building Ejike a mausoleum in my heart. With my own tears, my own sweat, my own blood.

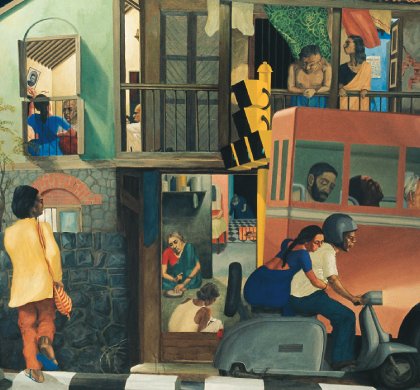

Paresh treated me with the patience of a long time mother. The first morning, he had not forced me to eat but he had brought something to my room in the early evening. Naan and some sauce with cottage cheese in it. ‘I didn’t know whether you were vegetarian or not but palaak paneer is one of our favorites.’ He put the tray down and left. I picked at the food, tearing up the bread and scooping up sauce with bits of cheese in it, eating because I did not want to be impolite but also because the aroma of the food triggered something in my stomach so that I actually felt hungry. The next morning, when Paresh knocked at my door to announce breakfast, I took a hurried shower and went to the dining room. I had expected to see other guests but Paresh said the three other guests had already eaten and scattered themselves into the city. One was a young researcher from Australia, writing a book on Delhi. ‘I asked him what his book would be about,’ Paresh said. ‘And he said it was about the chaos and beauty of the city.’ He spread his hands out and laughed as if the thought of an entire book on his city amused him. ‘You should go out too, see this chaos and beauty,’ Paresh said, the residue of his previous laughter still on his face, making his eyes shine as if they were polished stones. Maybe it was his background in psychology and his foray into grief counselling but Paresh was persuasive. I found myself, not quite half an hour later, sitting in a tuk tuk on my way to Lodhi Gardens, armed with instructions from him to also venture to Khan Market and try Mughlai rolls at Khan Chacha. ‘You cannot come to Delhi and not do this,’ he said. The rickshaw wove through the challenge that was Delhi traffic, complete with blaring horns and stray dogs and cyclists and beggars. I imagined telling Ejike how reckless my driver was, how I held on to the side of the tuk tuk in fright, certain that any minute now, we would be in an accident.

I had not talked to anybody about Ejike. Not really. The friends and the family and the colleagues who burst my house at the seams after his death handled his name like a taboo. When it was spoken, it was whispered, not as a prayer but as something dreaded. And never if they thought I was listening. The food they cooked and the newspapers they brought me and whatever conversations they brought up, were all done to plug holes through which his name might inadvertently slip. What was it about death that scared us so much? That made it impossible to relax around the newly bereaved? Maybe I would have done the same in their shoes but it upset me. It occurred to me the moment I stepped out Delhi airport that first day, that maybe that was what I had come so far to avoid: people treating me like something fragile. A place where I did not have to talk about Ejike in the past tense, where I could present him as a living husband waiting for me back home, his keys tinkling their music through the house.

Another thing Indians are is this: curious. From tuk tuk drivers to market traders, people asked what your good name was, where you were from, if you were married. Paresh did not need to ask my name or where I was from but he asked if I had a husband. Back home, I would have taken it as a sly but cheesy pick up line but I had been in India for over a week and knew that it was conversation and nothing else. ‘I do,’ I said.

‘He doesn’t want to see India?’

Silence. This was the moment when I could choose whether Ejike was dead or still alive. I wanted Paresh to treat me like any other guest, not a widow. Not a newly bereaved to be wrapped up in tissue. ‘He’s dead.’ I held my breath. I watched for the palpable shift in the air, the apologies, the embarrassed, ‘I am sorry, I didn’t know,’ that would mean that he would leave me alone with my sorrow, that he would no longer try to persuade me to see the ‘chaos and beauty of Delhi.’ Paresh looked at me and said, ‘I am sorry to hear that. What was his name?’ Gratitude and relief gushed through me like a torrent. ‘Ejike. Would you like to see a picture?’

‘Please.’

I spent six weeks in India and allowed Paresh to draw me an itinerary. I surrendered to his knowledge and allowed him to accompany me when he could. I told him how Ejike would have complained about all the heritage sites (he wasn’t one for sightseeing). Despite the Taj Mahal’s dizzying beauty, he would have hated the horde of photographers crowding tourists for pictures. He would have found Agra Fort too crowded and would have complained about the six hour express train ride to Jaipur to see the Hawa Mahal and the Amer Fort (where I passed up the chance to ride on an elephant). ‘He would have said,’ I told Paresh when I returned to Delhi, ‘He would have said what’s the point of going all that way when I can see it on google?’ ‘Philisitine!’ Paresh shrieked, wagging his finger dramatically like a scolding teacher at the absent Ejike, and we both doubled over in laughter. It was nice to be able to not just talk about Ejike but to make fun of him as well. It made his death somewhat less final. It made it lighter, like something I could manage, like dough I had beaten to thinness. It was there but I could, finally, see through it.