Pickpocket

The phone has a way of ringing in my bag. It sounded like an anxious mother calling. Ma was trying to reach me. She usually does when I am at the supermarket, crossing a busy street or in the middle of an interview. I dug out the phone. The screen showed three missed calls and a text message. ‘Sarthak is dead’.

This news didn’t put me on the next flight to Kolkata but I felt miserable for Shyamolee. She had been married to Uncle Sarthak since 1982. Personal mythology would have it that the matchmaking was thanks to me. Apparently, even at five years of age, I made decisions. Of all the wrong decisions I had made, this seemed irreparable now. Shyamolee, though, was perhaps fifty-five now, had too much life left in her to be relegated to the orthodox branch of the outdated Bagchi family tree. Madonna was fifty-nine but then, Shyamolee lived in Narkeldanga, Kolkata 700011.

There was a little party at home this evening. A birthday party for my husband who was on his way back home from coordinates beyond the GPS grid but would turn up before midnight.

Uncle Sarthak and my father were second cousins. They had nothing in common except their surnames. My father a bureaucrat, ate puri-aloo with a fork and knife and spoke Bengali like a Parisian. My mother used to teach Mathematics in a suburban school during the day and in the afternoon, built bridges over the telephone. My sister had blossomed into all that a mother would want, that’s what Ma believed. I wanted to believe that I was someone a father would take pride in. I just didn’t fit in anywhere.

My father had thought nothing of Sarthak. Over his whisky he even called it suicide, my mother reported when I called her back.

‘… Ma, what do you think?’

‘It was an accident, of course’

‘Ohh!’

‘Sarthak fell off a suburban train, he was returning from Hasnabad’

‘Where is that?’

‘Near Taki’

‘Where is that?’

‘Is that important?’

‘What would he want there?’

‘Some street play for the security forces. After that, on his way back, he must’ve had one too many.’

‘You said he stopped drinking after his second heart attack’

‘Ha!’

‘Means?’

‘It is alcohol not a hapless day job that one can just quit’

The pressure cooker called me. Potatoes had to be turgid yet soft. I was attempting the Kashmiri dum aloo. She said she would call back later. She was going to Sarthak’s house.

I brought out the prawns. Shelling them distracted me from the day. I had cried too much when the incident hit me. How was Shyamolee now? Was she the same young woman I had seen as a child in 1982. That was a June. The first day at the Marybong Tea Estate came rushing back to me. That is where the Chatterjis lived, on the estate. Jatin Chatterji, her father was someone important there.

I had noticed Shyamolee’s impish smile from behind a curtain. Saw her practice Kathak; her continuous twirls got me dizzy. I had started spinning where I sat, rather stood. I remembered her as ‘Lee’. She had brought out ‘Phantom’ cigarettes from an old tin box and pretended to throw smoke rings in the air, I had tried the same with the drumsticks on my plate.

We, Bagchis had driven up towards the tea estate after the Darjeeling Mail brought us to New Jalpaiguri. We were seven of us who had gone there to look for a bride for Uncle Sarthak.

Seven Bagchis in two white Ambassadors found it tough to maintain a conversation without tripping into family gossip. I pretended to be asleep but relished every morsel of juicy detail about every skeleton in most cupboards.

Nostalgia was wiped out with the sting of garlic tempering in mustard oil. The alarm went off, it was time to order the cake. I did.

‘Will there be a message on it?’

‘Happy birthday Mihir.’

‘Meer?’

‘M-I-H-I-R … and please could you send change for 2000.’

‘Ok ma’am.’

My playlist volunteered the song that Ma was humming that June, en route to Ghoom, ‘Chupi Chupi cholay na giye’. The two cars pulled over just outside the Ghoom Monastery. Uncle Sarthak’s mother had made some noise about missing a trip to the monastery. Ma had tutored us about what we could say and what we couldn’t.

Uncle Sarthak had asked Baba for a cigarette. Baba had snubbed the demand. On the rebound, he had bummed a bidi from the driver. On my appeal of ‘please don’t smoke,’ Uncle Sarthak had thrown the bidi away after lighting it. It had tumbled somewhere down the valley. My father had erupted about forest fires and how it’s a potential killer in woods like these. Much to everyone’s horror, Uncle Sarthak dashed towards the valley and leapt into the forest to retrieve the butt of the bidi. The Bagchis had held their breath. Ma showered wisdom in an undertone, ‘It has been raining all along, everything is damp.’

On his return, Uncle Sarthak had yet again escaped to silence. The silence had much to do with imminent rejection.This was his thirteenth voyage to find a bride. Each time the girl had turned him down.

The white Ambassadors were two moving dots in the last stretch of seven kilometres to the Marybong Tea Estate, District Darjeeling, West Bengal.

In the last ten minutes, Uncle Sarthak’s sister, called this trip an utter waste of time. She couldn’t quite understand why a girl, with an upbringing with colonial overtures, raised in the stunning Terai slopes of a tea estate, student of Dow Hill School, the only daughter of the Chatterjis would even agree to do anything but a literature major somewhere in the UK. Why didn’t she mind meeting one Sarthak Bagchi and exploring a shift to Narkeldanga, Kolkata 700011? We all remained quiet. Ma resumed humming, only this time, a song about hope. The cars one after the other, glided into the porch of the Chatterjis.

Mrs Chatterji was there to receive us. Other women of her age hovered around. Some in chiffons and others in Dhakais. Till date, I hope when people come forward with folded hands and say something nice, there is something good in there which wakes up a new world between two people.

My phone rang, it was Ma again, this time asking if it was a good time to talk. I told her I was peeling cucumbers. Ma seemed suspicious about the menu. She continued with what she gathered at Sarthak’s house. Not too many had turned up. Then she added gently that Monday afternoons weigh in favour of work over mourning. I blurted foolishly, ‘Sad part is, he died alone.’

‘We all do but what’s sad is … he even lived alone.’

‘No he didn’t, Shyamolee kaaki was there for him … always.’

‘That is what you’d like to believe. They were always quite odd.’

‘Hmm … I’m not even sure why she said yes to him.’

‘Don’t lose sleep over it now.’

‘But I did … I do.’

Ma fell silent.

‘Each one them in their family, pulled my cheek that day in June and till date they gush.’

Ma remained silent.

‘Each time I am reminded that it was me, who showed them a sign.’

‘What sign?’

‘That visit, then onwards, I started calling Shyamolee … kakima.’

‘You actually let that worry you?’

‘For all the things that went wrong in their life, I feel responsible.’

‘It’s because you are hitting forty and not having enough sex and starving yourself silly with a new diet every fortnight. Go to a salon before the party.’

The line went dead. I stared at the phone long after Ma hung up.

I looked up my contact list for Shyamolee’s number. Of course, I didn’t have it.

We hadn’t spoken ever since I shifted to Bombay. That was twelve years back. Facebook threw up pictures of weddings, baby showers, Pujo and vacations. Shyamolee didn’t show up in any. I don’t know why I stalked her life, but I did. I was guilty of finding her a husband.

It’s easy for the mind to race back, when you want it to. What it doesn’t allow, however, is a time machine, the ability to tinker with what really happened and how events unravelled. That would be a superpower I wanted. I didn’t know where we stood now after Uncle Sarthak’s death. A legend was being made each day and crafted with ease. Most of us nurture personal myths. Myths count, unfortunately.

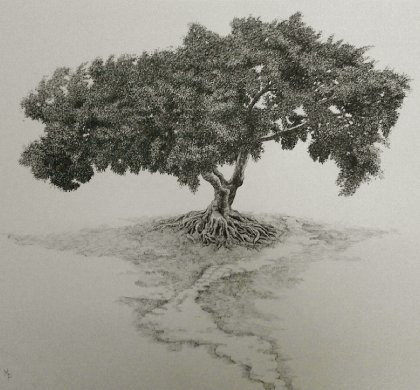

The five-year-old me, had still not stepped out onto their porch. Clouds took turns to visit, as their bungalow looked at the Himalayas. Then I wanted to believe this was magic. I wanted to carry home some fairy dust.

The patriarch, Mr Chatterji senior on a wheelchair, had wheeled out to the car we were in. He called me ‘Little Miss Bagchi!’ I had been curious about his wheelchair which I thought was his personal car. Thought he was too lazy to walk around the huge garden and I had told him so.

That wet June day had flown past. The Chatterji living room had turned into an exciting place of cordial exchange. From where I was, all I could hear was the kitchen and its familiar sounds.

I felt privileged when my newly acquired friend with his grey-haired crown and his ‘car’ and I, were served lunch like monarchs across a big dining table. We were made to sit across each other at the far ends of the table. The chandelier blinked each time he cracked a joke, almost on cue as if it had a mind of its own. At one point it blinked for a long time like dancing to a tap dance. We both looked at it.

Perhaps this is where we had missed seeing Shyamolee in her kathak dress, steal into the house through the rear entry. She had left the ghungroos in the backyard and tiptoed in and continued the kathak whorls, when I saw her. Shyamolee had certainly known that a prospective groom was coming to ‘see’ her but she remained intrigued by her grandfather playing with the five-year-old guest.

‘Please marry my uncle. Be friends with him. Someday, if you do katti with him you can come can come home, stay and sleep with us.’ Each time I cringe when I remember my appeal that same evening in June. There was an audible silence in the porch as those words were said. Moments later the cars whisked us away.

No one in our car spoke for the next hour. I had no clue what had befallen them. I had spent a happy day and now we were heading to meet my sister in her charming school which looked straight out of a fairy tale. I could never tell anyone that she thought I was a sissy to believe in fairy tales. She was much older and was already listening to Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. On good days, I liked the fact that Didi and I couldn’t ever have a conversation. My childhood needed me to invent friends who were imaginary. My imaginary friends had never let me down but that didn’t mean I stopped looking for them in real life. Like when I met Shyamolee next. I called her Lee, not aunt or Kakima or any such thing.

She had agreed to marry Sarthak. Prejudice radiated from my father, something about her coffee bean skin tone. Made no sense to me then but I remember my mother finding courage to stand up to him in the light of wanting to hush up relatives that would first look for chinks in Shyamolee’s armour. Few said she was a divorcee, others said that she actually was Chatterji’s driver’s daughter and Sarthak was a catch. Sceptics said that she was dumped by her earlier fiancé and when she found about her pregnancy, she had no choice but to marry the next bloke who came to her doorstep.

These thoughts had remained in a scrapbook of memories. I rummaged through them often.

The doorbell rang. Someone had sent flowers for Mihir. There was no name on it. I thought it would be a better idea to have them around and find out later about the sender. Suspicion can be coached to be positive. It works at times like these, when you want it to. The humid August afternoon indulged the fragrance of the yellow Lilium. Friends that evening would be at the mercy of Orient ceiling fans and the ventilation of a tenth floor apartment. The weather would be a leading topic that evening but I had more urgent first-world concerns. The booze had not yet been delivered. I made a call to the wine store but disconnected before anyone answered the phone. I was in no mood to listen to some lame excuse. I would rather run and choose myself before that dash to the salon.

At the wine store, they startled me. ‘But your order has been received madam.’

‘How? No one is at home.’

‘Sa’ab must have received it … aye Girish, kisku diya saaman?’

Girish looked flummoxed at first, then recognised me. ‘Blue Mountain, tenth floor, B-wing … tip bhi mila.’

Unlikely that Mihir would land up without calling me. Especially, when he had come home after four months, two weeks and six days. But then, with a husband one never knows. I started a quick trudge towards home. This time my phone rang. Of course it rang when it was inside the deepest pocket of the bag.

I couldn’t even begin to think of a break-in but bad things like that happened. It must be the watchman calling I thought, but it was Mihir. With a happy ring to his voice, he said that he wanted to surprise me. I stopped in my tracks and attacked him with a flurry of concerns which he neutralised with his effortless charm. And just when I almost sought permission to return a little late, he volunteered to pick me up from the salon in his weather-beaten jeep. I thanked him and was about to hang up when he said ‘Happy birthday to me, Roma’. After all that planning of a surprise birthday party I had actually forgotten to wish him. I asked him if I should drop the salon idea and come home. He ruled out the idea saying that he preferred the idea of being surrounded with beers and anticipation, rather than a frazzled wife.

I sent Ma, a selfie with my new haircut. She called back instantly.

‘You are making certain that Mihir finds himself a mistress’

‘Where did that come from?’

‘Women don’t wear their hair this short!’

‘It looks nice.’

‘Says who?’

‘I don’t need anybody to tell me that.’

‘They may not say it but men still like silky long straight black hair.’

‘In that case maybe he should go and find himself a mistress.’

Ma disconnected the phone.

I called Ma back, she was, of course, sulking, I resumed without apologies. ‘When does the mourning end? Officially I mean…’

‘Tenth of the next month … no … eleventh, why?’

‘Maybe we shall come by to see her …?’

‘Mihir and you?’

‘Maybe…’

‘Welcome welcome.’

‘Will you please give me her number?’

‘Shyamolee’s?’

‘Yes.‘

‘Are you sure you want to do this?’

‘I should have called her long back.’

‘Sarthak is … was your father’s second cousin, how does that even…’

‘Even what Ma, anyway there is nothing I have to fear right?’

‘You have enough running around already Roma.’

‘I do … it’s just that I don’t know what I am running from.’

The pedicure felt nice. My phone beeped. There was an sms with a number, a number I dreaded calling. I could have called Shyamolee – Lee – when Uncle Sarthak lost his third job in a matter of two years. I could have called her when they lost their first baby to dengue. I could have called her when she got a job with the Bishwa Bharati University. I could have called her when Uncle Sarthak had the first bypass surgery. I could have called her when she started Kathak tuitions near home. I could have called her when Uncle Sarthak lost money at the races.

I dialed her number. I hung up before someone could respond.

Hours later, in a stupor of regretting making that call, sleepwalking at my own party, the phone glowed, ‘Lee calling’. I found a corner and some courage. She just cried, I listened. Just as I thought I ought to hang up, she said, ‘They found his body the next morning. Someone pushed him off … or maybe he fell?’

‘What do you think?’

‘I think it was a pickpocket, must be new at his job, picked the pocket but lost control.’

‘Ohh?’

‘You know Roma, they didn’t find his wallet.’

‘Hmmm…’

‘I knew he had written a long letter to me, he had been talking about something he had to tell me’

‘Ok … ay.’

‘He mentioned he didn’t know where to begin…’

Mihir had come and sat next to me, I curled up to him for comfort. The neck rub that he was so good at, came in handy. Friends hooted at us with joy, mixed with envy. Mihir retreated to his friends, left me with Lee and my phone. I could hear the noise the friends made and his repartees were cool.

I tried to focus on the phone, truly. ‘… maybe the cops can help to find a pickpocket.’

‘Ma Baba don’t want cops in this’

‘… right…’

‘All the eyewitnesses find it unlikely … they say the bogie mostly had soldiers.’

‘Is it?’

‘The petty thieves would stay clear right?’

I looked at Mihir, I read his lips, he had just spoken about the Hasnabad local during this journey back home. What Lee said next was all a blur. I drowned data in vodka. But I overheard him talking about his train. Singing and returning from his project, this time close to Taki, the stunning Indo-Bangladesh border. Soldiers sing when they are happy, he shared with his friends. I had no recollection beyond this moment. The music that night had turned too loud.

Next morning, the rain woke me up. I was still on the balcony, in my favourite red beanbag. A warm cup of tea touched my shoulder. Mihir was holding my mug and his. The morning was rain-drenched. Traces of the party reminded me of last night. I wasn’t sure if I was happy or not, I looked at the last received call. It was Lee’s.

And then, Shantabai surfaced grumpily from the inner wing of the flat. She wanted to claim the balcony. She had wet laundry tucked in her arms. Mihir and I made way for Shantabai.

Mihir showed me the iPad, his inbox was full, I wasn’t sure what I had to see.

He kissed me on my forehead and I rested my head on the table. In my hangover, I noticed two e-tickets. He had booked us to Kolkata for the tenth. He said Ma had called to wish him last evening. He added that Ma asked if we both were expected in Kolkata on the tenth. Mihir had said yes. The tickets were booked this morning.

Despite a pulsating headache, I soon got lost in the kitchen and menu for the day. Shanta on her way out, came towards me straight, picked up her umbrella from the service area, and instructed me to check pockets before I sorted them for washing. ‘I always do,’ I retorted.

She alleged otherwise. She held out a wet wallet in front of me, I didn’t recognise it. She opened it and showed me a photo, it was my photo. Me, Roma Bagchi, in an odd wallet, which I didn’t recognise. ‘Where did you find this?’

Stupid question, she retorted and showed me Mihir’s grey trousers. The same pair of cargoes that he travels in, mostly. She added that I looked better in this black and white photo.

Mihir was unwrapping gifts. I snuck out with the wallet, there was a letter in there, something in Bengali. Words all smudged and gone because of soap and water.

‘Where did you find this?’

‘Find what Roma?’

‘This wallet!’

‘Maybe you are forgetting a little detail.’

I could almost hear my temper rise, Shanta banged shut the main door as she swaggered away with her umbrella.

‘I am forgetting detail Mihir … or you want to tell me something?’

‘If you want me to.’

‘I do.’

‘Your photo reach a strange wallet without you knowing it?’

‘ohhh!’

‘exactly…’

‘Do you know his name … who he was?’

‘I have no idea who he was, do you?’

‘Where is he?’

‘Maybe in the morgue…’

I kept looking at Mihir , not sure if I was hurt, angry or scared.

‘You … for this … for a…?’

‘Borders are a funny place, people die’

I wanted to dry the text of the letter but my feet stayed there.

‘People die or they are killed…?’

Mihir grinned, ‘Same difference…you wouldn’t understand these things.’