Tourists have a singular view of reality. They look upon sightseeing as they do on fiction: part truth, part fantasy. Proper tourists are quick to forget the picturesque places they visit, as they keep up with their itinerary. But they also accept the tales told by the guides without question.

A few annoying exceptions are always there. People with no faith, fond of saying ‘so what?’ to everything they are told. Tell them, the first raindrop falls like a tear on the grave of Mumtaz Mahal in Taj Mahal at Agra, and they will shrug: so what, that’s what marble roofs do – absorb moisture and leak. If everyone turned non-touristy, what would happen to the poor guides? Go swell the unemployed horde, that’s what. But a lot of thrill and romance of travel would be lost.

Bet you saw Devanand’s film, Guide. When I first saw it in my youth, I refused to believe a guide like that could exist in real life. But when I saw it again in my old age – you may call me elderly, but I have no objection to being called old – I thought it could well happen. We grow more romantic with age, fatalistic too. And then, would you believe it, I found my remarkable guide in Mandu, Madhya Pradesh.

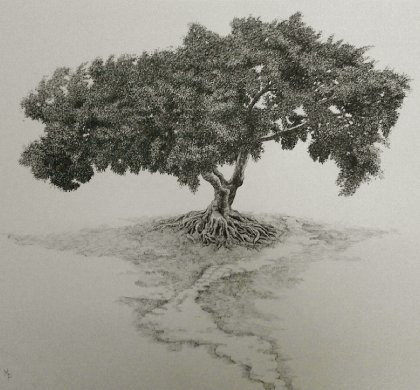

Mandu did not boast of many tourists. I could look far into space without the crowd butting in. Despite a profusion of gnarled trees of peepal, banyan and khurasani tamarind, the hilly landscape looked almost empty. Most of the ostentatious man-made buildings were in ruins. The lesser ones had survived and merged in the natural surroundings. Nature is one hell of a dame sans mercy, not satisfied with less than total surrender. But she is not impatient, quite willing to wait for the right moment and opportunity. I felt at peace in Mandu, surrendering to the natural order, rid of ego and angst. But for how long?

I reached Jahaz Mahal to find a host of guides, mostly children, chasing a small number of tourists. Child labor! See, there was no escape. Wherever I was, the sorry state of society managed to unsettle me. Enough of sights and fables, I told myself, time to return to reality.

I turned round to find a boy of fourteen asking me, ‘Want to see Saat Kothree?’

I waved him away, but did not expect to escape the sales spiel. But he did not say a word; gave an arrogant stare, shrugged and walked off. His nonchalance shouted loud and clear: stop me!

‘What’s to see there?’ I called.

‘How’ll you know if you don’t see,’ he said.

My-my, so guides could be non-touristy too!

‘Surely you know its story. How far is it?’

‘Far enough to need a car. Have one?’

‘We’ll hire one.’

‘Let me know,’ he said moving away.

‘Are you a guide?’ I called again.

‘What else?’

‘Don’t you go to school?’

‘Why not? Its two now, isn’t it? The school closes at two, doesn’t it?’

Great! A mini edition of Devanand. Why did I always end up with mini editions!

We reached Saat Kothree, the Seven Little Rooms. Not bad as views went. Hills and valleys merging and emerging from each other for quite a distance, making the expanse look, well … expansive. We left the car and climbed a fair distance to reach a high flat rock. A few roughly hewn steps, about thirty, led the way down to the other side. Going down, I was surprised to see small puddles of water here and there. Strange! There had been no rain. I recalled someone telling me, ‘Had a drought not hit us again this year, the hills would have been bubbling with waterfalls.’

We managed to negotiate the slushy, uneven steps without slipping to reach a middle-sized pond. The size of a small room with knee-deep water; more like a square bathtub with a stone skirting. No, mustn’t say that. Hadn’t I seen a small alcove as we entered, complete with a priest and his quota of implements, lota, kamandal, flowers, joss sticks, incense, charanamrit, aarti plate and coins? Ergo, it was a temple! There was nothing ornamental about it though. What was there was just there. Still to call a temple a bathtub could invoke a curse. From whom, the nondescript priest? What a ludicrous thought! I had barely time to smile when the ground fell away from under my feet. The water climbed to my chest. The guide hung on to me, otherwise I would have gone under. Mahadev-Mahadev, forgive me, I never said it was a bathtub! The mind, you know, is one hell of a jester; who knew what oddity it would conjure?

Taking small careful steps, we reached the far end of the stone skirting. I realised it was the end when my knees hit a stone boundary. I climbed over it and found myself in yet another pond. Chest deep hot water encircled me. The sudden onslaught of heat on my chilled body made a drowsy languor steal over it. I was reminded of a health club seen on the small screen.

‘Stop this nonsense this instant,’ I admonished myself! ‘Focus on the water above chest level, the slimy stones below; one false step and you’ll fall bang on Lord Mahadev himself.’ There he was, ensconced on a flat stone platform protruding above the water. Not the bust, only the lingam. I had to climb over yet another skirting to reach it. The ground below must have gained height, because the water level fell to my waist. But it was much hotter now, like a sauna bath! Damn! Things I had never seen, felt or touched were jostling my mind via the idiot box. As if I was incapable of thinking for myself.

The quick change from cold to heat made my nose itch. I tried to stifle the impending sneeze, but despite my sincere effort, a mini sneeze burst forth as I put my bowed head and folded hands on the lingam. Fortunately no one but Lord Mahadev heard it. When I raised my head, I found I could see much better. I saw two small rooms branching off from Mahadev’s pedestal. Both had stone images inside, one of Ganpati, the other of Nandi. I bowed to them from afar. As I turned back, I realised one room was missing. One, two, three, in a straight row, I counted, two on the side; that made five. Take the priest’s alcove for another small room; altogether six. Where was the seventh room? And why was there no image of Parvati, the consort of Mahadev with or without him?

We circled back to the priest. The aarti plate was offered, purse lightened, prasad received, and we were back at the door. I peered around the priest: right, left, over his head, but did not see any other room. Where was the seventh room? Outside … perhaps?

We came out. As I sat on the top step to squeeze my wet salwar, I saw the priest come out, tying the offering of coins in his towel. He shut the door and turned the lock. Astounded, I could not help exclaim, ‘Why are you locking the ponds?’

He stared at me, ‘What if someone pollutes the water,’ he said.

What was left to pollute? Hadn’t we all splashed in it with dirty feet? But before I could say so, he had run down the steps and disappeared.

‘Shall we go? We have to see one more place before sunset,’ the guide was saying.

‘We don’t have to see each and everything,’ I grumbled, shaking out my wet kurta, but followed him.

Back on the upland, we were greeted by an incredible scene. A woman sat on a small ledge jutting out of the uppermost ridge, wringing her hands. At arm’s length lay a hundred-foot deep ravine. Suicide! The fear of startling her made me suppress my scream, though I realised an instant later that she was too far away to hear me.

‘What is that woman doing?’ I whispered to my guide.

‘Washing clothes, what else,’ he shrugged his shoulders.

But of course! I now saw the thin stream of water falling out of a tiny fissure in the rib of the ridge. The woman sat on the small ledge underneath, washing clothes. One false move and she would fall in the ravine, shattered to smithereens. That tiny trickle was the only thing resembling a waterfall we had seen that day. It was, after all, yet another year of drought.

There was so much water there in the natural tubs at Saat Kothree, hot and cold. One had to mix a little detergent, and the clothes of the entire village could be washed at one go. Better than a washing machine. But the water lay behind locked doors; not to be polluted.

My guide was running down the hills, agile as a goat. I kept turning back and looking at the woman as I dragged my feet after him. But as the hilly terrain grew rougher, I was forced to keep my eyes glued on the path and lost sight of the woman.

We came to rest atop a large plateau. Open blue sky branched far into the horizon on both sides. A deep valley full of centuries-old gigantic trees looked up at the sky. But neither they nor the mountain peaks dared reach it. In other words, everything needed for a sketch of a traditional sunset was present. Collective memory is one bitchy mistress. Despite my skepticism, it forced me to pause and gaze at the sun playing the game of death on the horizon.

‘What’s to see here?’ I asked the guide.

‘We sit here,’ he said, and sat down cross-legged on a flat rock facing the setting sun. I sat where I was, on another rock. The sun began to set slowly. As it did everyday. It set, it rose. What was there to see in it? There was no sense of loss in losing it. One knew it’d return even as it left. It did convey a sense of momentary death, though, otherwise found only in orgasm or meditation. A quiet stillness enveloped everything including me. I was determined not to surrender to romanticism, so decided to tell the guide, I didn’t want to sit there. But one glance at him made me hold my peace.

The setting sun suffused his motionless form with a crimson glow, turning it into a fountainhead of incandescent light. Golden rays emanated from his broad forehead. ‘Evening star!’ I mumbled spellbound.

Just then, the sun dived into the horizon and darkness fell. As it does every single living day. He got up on cue, came to me and said, ‘Let’s go.’

I scrambled up, saying, ‘It grew dark so suddenly. Do you think the woman would have left the ledge earlier?’

‘Who knows?’

‘She could lose her foothold in the dark.’

‘Sure could.’

‘Then…’

‘She’d crash into the ravine, what else? Shall we go?’

How could a child talk of death so nonchalantly!

‘She is used to the terrain,’ I begged for reassurance, ‘Surely she’d climb down safely?’

‘Did you like the sunset?’ he asked.

‘Damn the sunset! Answer me.’

‘You are a no-good tourist,’ he said.

‘Why?’

‘All this that Master Saab calls nature – mountains, forest, waterfalls – tourists call a place to picnic. But you … you ask too many questions.’

‘Nature is no picnic. It’s a strict Master Saab. Two and two are always four; it offers no concession. Every single day, the sun sets; darkness falls, the next day…’

‘Yes,’ he broke in, ‘One whistle and the game over. How quickly the sun set! Phut!’

Dense darkness covered everything, the upland with the seven rooms, the hills and the valleys. I would not have seen the woman on the ledge, even if she was there.

‘Why don’t people break the lock? There’s so much water at Saat Kothree.’

‘What if the water got polluted?’

‘Who’ll pollute it?’

‘She who washes clothes on the ledge, who else?’

Was he a child or a mini edition of an old man?

We started back for Mandu. On the way, we passed through a dense jungle. ‘Stop the car,’ he said, ‘I live here.’

He got down and started to walk away as soon as the car came to a stop. ‘Stop-stop,’ I had to call out, ‘You forgot your fee.’

He refused the money I held out, saying, ‘What fee? I didn’t do anything.’

‘You showed me Saat Kothree, didn’t you?’

‘I showed you only six rooms.’

‘True.’

‘If you had asked, I’d have told you why six, not seven, wouldn’t I? I could have taken the fee then, couldn’t I?’

‘You are right. I am a no-good tourist.’

He shrugged.

‘Why don’t you tell me the story now, please-please!’ I begged.

He nodded and began to narrate the story, standing by the side of the car. As I sat still inside, listening to him, I travelled a long way back in time.

‘A long time ago, more than a hundred years, there lived in this village seven virgin sisters. Each of the seven virgins declared she was Sati, the true consort of Lord Mahadev. Each of them, adorned like a bride about to enter her nuptials, propitiated Lord Mahadev with due worship and supplication. None was ready to enter into marriage with mortal man. The village folk laughed, saying, poor Lord Mahadev, fancy him not finding any other female for a consort! They duly tried to arrange earthly marriages for them. Unfortunately the father was too poor to give a dowry seven times over, so not one got married.

‘Then it came to pass that the village found itself in the grip of a severe drought for the third year running. A few ponds and waterfalls, which had escaped running dry in the past two years, dried up now. The village keened in grief. The elders declared that the drought was a punishment for the sin of seven unwed females gallivanting round the village. A woman’s dharma enjoined that she marry and run a household. These women were not virgins or satis but immoral women desecrating the village. If the father could not arrange proper dowries to get young grooms, let him marry them to widowers, but marry they must. Soon as the verdict was in, all the doddering old men of the village came forward asking for this or that girl’s hand in marriage. “We’ll soon see them all yoked,” the village exulted.

‘But alas, not one became a bride. A few days went by when they heard a herald proclaim throughout the village. “Come one, come all on the next moonless night to the house of the seven sisters. After ceremonial worship of Lord Mahadev, they will, one by one, throw themselves into the hundred foot deep ravine below. With each leap, water will spring forth from mother earth. Seven virgins: seven springs! Come one, come all, see the miracle with your own eyes.”

‘As the twilight of the moonless night slunk by, it saw the entire village gathered by the side of the deep gorge. On the other side of the gorge, stood the seven sisters! Henna on the palms, crimson paint on the feet, vermillion in the hair parting and brilliant red dots on the foreheads! They wore no jewels, but each held in her hand a gleaming aarti plate with a lighted earthen lamp. That was enough adornment. The village stood bedazzled as its eyes feasted on seven beauteous beings. The young men heaved a collective sigh, what a waste not to have made them theirs! How paltry seemed a dowry, before their radiant beauty!

‘The eldest sister touched the aarti plate to her head, chimed a silvery cry of har-har Mahadev and leapt into the deep ravine. The village held its breath and waited but no water sprang forth. Then the second sister chanted har-har Mahadev and jumped into the gorge. Nothing! The third, the fourth, the fifth sister followed. All around them, the hills and the valleys reverberated with the chant, har-har Mahadev but not a single drop of water spouted anywhere. The villagers turned into stone. No one could move or speak. The seventh sister stepped forward with her head bowed over the glowing aarti plate. She came to the edge of the ravine, peered into it and stepped back. Again she came forward, peered and stepped back. This happened thrice. Some villagers wanted to cry, “jump”, others “don’t jump”, but too petrified to give tongue to their thoughts, no one uttered a word. The twilight faded and the impenetrable darkness of the night, not host to the moon, took charge. The evening star alone twinkled bravely in the dark. The villagers could no longer see the girl on the other side of the ravine. Some of them began to clamber over the hills to reach where she stood hesitating. Before they could, they heard her give a tumultuous cry, “Mahadev-Mahadev-Mahadev!” Their blood ran cold. They stood transfixed where they were. All of them clearly saw a divine being come running and take her by the hand. Hand in hand they ran at a furious speed, away from the village, crossing hillock after hillock. Water sprang up wherever their feet touched the earth; cold from the footmarks of the virgin sati and hot from the footmarks of Mahadev.

‘Early next morning, the villagers built a stone skirting to hold the water within ponds. Seven ponds thus came into being. Some had cold water, some hot. The lingam was installed in the last pond in the name of Lord Mahadev. The whole complex came to be known as Saat Kothree or Seven Rooms of the virgin satis. But before the next full moon was due, a murmur began in the village, growing louder and uglier by the day. First the young men whispered that Mahadev happened to be the name of the second son of the lowly shepherd Bhimdev and that he was missing from the village. Then it was rumoured that he had gone missing on the very night when the six sisters threw themselves into the ravine. Finally it transpired that it was no divine being whose name the seventh sister had called, but that rogue Mahadev, and it was he who took her away. The vixen had eloped with her paramour under cover of darkness before their very eyes! The villagers looked hard and long for them but failed to find the sinful woman or her lover.

‘The respectable folk of the village grew worried; what if the vixen returned and polluted the water sanctified by the six satis? What if the tale of her immoral behaviour corrupted the young girls of the village? What if the penance of the six satis turned ineffective and the sins of the seventh sister spelt doom for the village? The elders convened a village council and decided that the seventh pond be filled with bricks and levelled, while the other six be joined together and the whole complex barricaded by a locked door. Five elders were chosen to oversee the locking and unlocking of the door daily and the conduct of the worship. The complex was renamed, Chaih Kothree or Six Small Rooms. But the name did not stick. People continued to call it Saat Kothree. A hundred years have gone by. All eyewitnesses of the incident are dead and gone but the name lives on, Saat Kothree.’

The guide fell silent. The story was done. Darkness engulfed us.

‘But,’ I protested, ‘the water sprang from the footmarks of the seventh sister, when she took Mahadev’s hand, did it not?’

‘They say the water did not spout until the degenerate woman had left the village. The piety of the six sisters took effect only after the seventh was over the mountains. Water had sprung from the spots where the six satis had fallen. Cold water because the six were pure; and hot because the seventh sister had made them shed bitter tears.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘that can’t be true.’

‘They say it is.’

‘And you? What do you say?’

‘What’s to say? All seven sisters called to Mahadev, did they not? He came only for the seventh, did he not?’

He fell silent. So did I. There came a time when one of us had to break the silence of that dark doom-night.

‘Why isn’t the moon out?’ I muttered.

‘It is Amavasya, the moonless night,’ he said. He then brought his face close to mine through the open glass of the car and whispered, ‘Every Amavasya the seventh sister comes to wash Mahadev’s clothes, at the edge of the ravine.’

Clammy with fright, I gasped, ‘Is that so?’

All I got for an answer was a receding laugh in the dense darkness as he disappeared from view.

This story was first published in Hindi under the title ‘Saat Kothree’ in the collection Mere Desh ki Mitti Aha, National Publishing House,Delhi, 1998.